It doesn’t take a genius to realize the U.S. budget process is broken.

The biggest reason for that is that too much spending is growing on autopilot. Now, Congress wants to double down by budgeting even less frequently.

Speaking to the Washington Examiner this month, Rep. Steve Womack, R-Ark., who co-chairs the Joint Select Committee on Budget and Appropriations Process Reform, suggested that lawmakers were considering moving to a biennial budget cycle.

“Just based on the feedback, I think the committee is coalescing around a biennial budget,” Womack was quoted as saying.

“I’ve not had anybody push back significantly,” he explained.

The proposal currently under consideration would relieve the budget committees in the House and Senate from pursuing a budget resolution on an annual basis. Instead, Congress would only pursue a budget resolution every other year, while continuing to pursue appropriations annually.

It’s a strange proposal for Womack, who is also the chairman of the House Budget Committee, to cheerlead. It would reduce that committee’s power yet further—but perhaps that’s exactly the goal.

This so-called “hybrid” approach is quite tempting for lawmakers, especially in an election year. Budgeting is about choices and trade-offs.

It’s not surprising that lawmakers would rather avoid the difficult subject of how to balance the budget and reduce the deficit when doing so is becoming harder each and every year.

With more than $15 trillion in debt to the markets, and with an additional $6 trillion the federal government has conveniently borrowed from its own agencies (including the Social Security trust fund), the U.S. budget process has enabled government largesse by default.

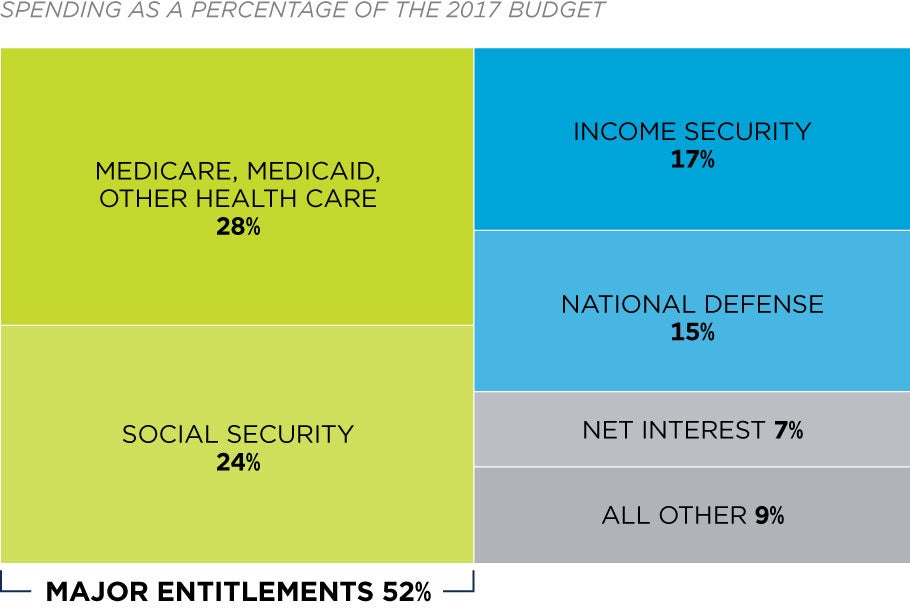

Autopilot spending on entitlement programs is the largest driver of growing spending and debt. With more than two-thirds of the U.S. budget going out the door on what are permanent appropriations, lawmakers have been able to turn a blind eye to lingering—and growing—problems in health care and other entitlement benefit programs, seemingly without consequence.

Just about the only part of the budget that gets regular attention from lawmakers is that part that requires annual appropriations. At $1.3 trillion, based on Congress’ latest omnibus, the casual observer can be forgiven for thinking that the discretionary budget, which funds defense and domestic agencies, is all the budget the U.S. government has to worry about.

Far from it, the vast majority of the $4.1 trillion in projected spending for fiscal year 2018 will go to federal health care programs and Social Security. These programs make up more than half of the budget, and their share is growing rapidly.

The budget resolution is the only legislative document that confronts Congress with the entirety of the federal budget.

Grappling with the worsening fiscal situation encourages lawmakers to put forth proposals to address growing spending and debt. The budget resolution is the unifying document wherein the majority party in Congress lays out its vision for the fiscal future of the nation.

In other words, the budget resolution matters.

The budget resolution is also the only way for Congress to invoke reconciliation, a powerful legislative tool that facilitates changes to taxes and entitlement spending by fast-tracking eligible bills.

Reconciliation most recently facilitated the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the most sweeping change to U.S. tax policy in 30 years.

Reconciliation is also a powerful fiscal tool lawmakers should leverage to pursue changes to autopilot entitlement programs that are driving the U.S. budget deeper into debt. Congress must spend more time reconciling tax and spending policies, not less.

Rather than concocting ways of abdicating yet more responsibility over the federal budget, lawmakers would do the American people a greater service by discussing ways of reviving the budget process as a critical tool to arrive at fiscal discipline.

One promising proposal would give lawmakers more of a stake in completing a successful budget process cycle. Lawmakers would only get paid if they first did their jobs.

“No budget, no pay” is one heck of an incentive to compel Congress to take the budget process more seriously.

Don’t expect lawmakers to suggest effective ways to revive a process they’ve let purposefully fall by the wayside. That kind of pressure—to perform in their jobs or be held accountable—will need to come from the outside.

Who’s ready to join me?