History is filled with Democratic scandals that often provoke the reaction, “If a Republican had done that … ”

Chappaquiddick is not such an example.

The incident, in which Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, D-Mass., allowed 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne to die while trapped in his Oldsmobile, likely belongs in its own category: “If any politician whose last name wasn’t Kennedy had done that … ”

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

The movie “Chappaquiddick,” which arrives in theaters April 6, runs on two tracks.

One is the long-overdue tale of how wealth, privilege, and power allowed a U.S. senator to orchestrate a cover-up and get away with something dastardly.

The other is how a very human Ted Kennedy struggled with walking in the shadows of his brothers Jack Kennedy (murdered while serving as president), Bobby Kennedy (murdered while running for president), and Joe Kennedy Jr. (killed while serving his country in World War II).

Ted Kennedy’s ailing father is Joseph Kennedy. After suffering a stroke, the Kennedy patriarch portrayed in the movie uses a wheelchair and, though barely able to speak, manages to utter a word of advice to his surviving son: “Alibi.”

Ted later responds to his father:

I’m not going to be the one defined by my flaws. Joe was the favorite one. Jack was the charming one. Bobby was the brilliant one. And what does that leave me, Dad? The fat one? The stupid one? I’ll tell you what, the one that gets in the most trouble. I can be charming. I can be brilliant. I’m the only son you’ve got left.

His father at one point tells him: “You will never be great.”

“Chappaquiddick” depicts Ted Kennedy as morally conflicted over how to handle the July 18, 1969, drowning of Mary Jo Kopechne, the passenger in the car he drove off a narrow bridge on Chappaquiddick Island, Massachusetts.

Even though the movie version of the surviving son claims he would experience a “new beginning,” we know he would continue to lead a life of poor behavior.

The movie shows Ted Kennedy as never wanting to be president, even as the Kennedy clan and the cohorts who surround him say he must. This admission may be true, since when he finally ran in 1980, he famously couldn’t answer the question of why he wanted to be president.

This film is a welcome shift in tone on Hollywood’s part. Even five years ago, it’s unlikely that top film producers would have made the Kennedy family anything short of heroic.

Conservatives likely will love this film, and not every liberal will hate it. It is a solid and believable piece of storytelling.

Rather than making Kennedy out to be purely evil, it portrays him as a deeply flawed and (don’t roll your eyes) even sympathetic individual, given the tragedies his family endured in the six years leading up to the 1969 accident.

That sympathy will assuredly reach its limits when viewers hear that the first words out of his mouth after the drowning are, “I’m not going to be president,” and when he wears an unneeded neck brace to Kopechne’s funeral to keep up appearances. Sure, he does feel guilt. But he’d have to be a monster not to.

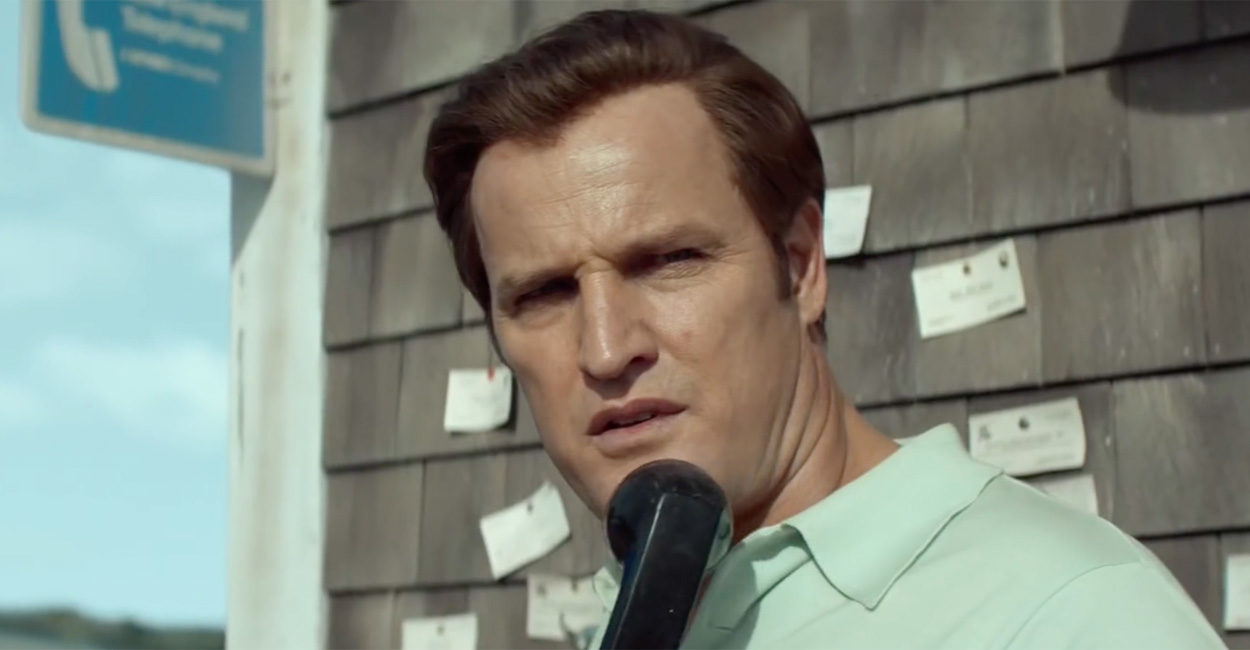

Jason Clarke, best known for playing Tommy Caffee, a New England politician on the Showtime series “Brotherhood,” plays Kennedy. Kate Mara, best known for her role as Zoe Barnes on the Netflix hit “House of Cards”—a character also killed by a politician—plays Kopechne.

Most out of character is comic actor Ed Helms, who plays Kennedy cousin Joey Gargan. As portrayed here, Gargan is consistently the angel on Kennedy’s shoulder telling him to do the right thing—first to report the matter right away, then to tell the whole truth, and finally urging him to step down from the Senate. Kennedy ignored all that advice.

Using the “everyone has flaws” crutch, Kennedy tells Gargan: “Moses had a temper, Peter betrayed Jesus, I have Chappaquiddick.”

Gargan replies: “Yeah, Moses had a temper, but he never left a girl at the bottom of the Red Sea.”

The real Gargan died just last December. After his estrangement from the Kennedy family, he spoke publicly about the spin and alibis the Kennedys considered to explain away Kopechne’s death.

Gargan’s advice gets drowned out by the devils on Kennedy’s other shoulder: an army of legal and political pros. This group of confidantes—which included former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and speechwriter Ted Sorensen—looked for ways to reframe the narrative.

Because of the conflicted senator’s early bungled handling of the incident, one crisis manager comments, “Bay of Pigs was a better managed operation.” Nevertheless, the pros manage to put together a winning public relations and legal strategy.

As with any historical movie that purports to shine light on what really happened behind the scenes, I’m a little skeptical of the dialogue and emotional conflicts. Yet there were ample media investigations into Chappaquiddick, and a few scattered voices such as Gargan’s did speak up.

The most notable voice was that of journalist Leo Damore, who released the book “Senatorial Privilege” in 1988. His account is being re-released to coincide with the movie under the new title “Chappaquiddick: Power, Privilege, and the Ted Kennedy Cover-Up.”

Ted Kennedy’s biggest concern in 1969 was the big newspapers and the three national television networks. One wonders if Kennedy could have survived a scandal such as Chappaquiddick in today’s 24-hour news cycle fueled by cable news and the internet, even with his famous name. I suspect not.

Ann Coulter’s line, “Being a Democrat means never having to say you’re sorry,” is tougher to support nowadays.

The #MeToo movement has forced Democrats such as Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn., and Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., to resign without ever having killed anyone. Not to mention Rep. Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y., whose sexting scandal forced him out of office in 2011.

Even politicians and commentators on the left have reassessed that President Bill Clinton should not have survived his impeachment scandal in 1998.

The problem with some conservative-leaning movies is they beat you over the head with a message. “Chappaquiddick” doesn’t.

The film will make you think both about history and our current political environment. It also properly recognizes the humanity of a politician while still drawing clear moral lines—and placing Ted Kennedy’s choices on a clear side of that line.