President Donald Trump hosted an event in the Oval Office in November to honor three Navajo code talkers who served during World War II. Characteristically, he made news when he referred to Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., as “Pocahontas” because of her contested claim of Native American ancestry.

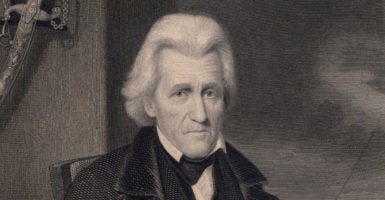

Also raising eyebrows was the fact that a portrait of President Andrew Jackson was prominently displayed during the ceremony. Commentators expressed indignation at this, given Jackson’s history with Native Americans, which culminated in the infamous Indian Removal of 1830.

Arizona state Rep. Wenona Benally, a member of a Navajo Nation, compared Jackson to Adolf Hitler, implying that for Trump to display Jackson’s portrait at a Native American event was equivalent to displaying a portrait of Hitler during a Hanukkah celebration.

Also well-known is Trump’s own affinity for Jackson—which some see as a link in the long history of American populism.

I will admit Jackson, whose 251st birthday is on March 15, is one of my least favorite American presidents. When studying his life, one finds much to scrutinize. He seems to be one of our most thin-skinned and least magnanimous presidents, who rarely rose above petty grudges.

His personal contempt for political opponents, such as John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Nicholas Biddle, spilled into the affairs of state and divided the nation. To many, his destruction of the Biddle’s National Bank was based on spurious economic thinking.

His long career fighting and confiscating the land of the Creek/Seminole peoples is well known. As the architect of the Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears, which led to the deaths of at least 4,000 Cherokee, Jackson remains the author of one of the great blots on America’s history.

For those who prefer the limited presidency drawn up by the Founders, Jackson ushered in a new and enlarged vision for the office.

Previous presidents saw themselves as playing a minimal role in policymaking, even signing bills they disagreed with because they saw policy as the purview of the Congress. Instead, Jackson, with the help of his spoils system, arrogated to himself a legislative role equal to that of Congress, incorporating his personal preferences into his signing or vetoing of legislation.

For those who lament the modern-day “imperial presidency,” Jackson was the first imperial president. And of course, Jackson was a slaveholder.

With all of that in mind, it’s easy to see why Jackson’s historical reputation has diminished. In a 1948 poll of historians, Jackson ranked as the sixth greatest president. In a 2017 poll, he fell to the 18th spot. Schoolchildren today, by and large, know Jackson solely for his culpability in the Trail of Tears episode.

It may come as a surprise that, despite all of this, I now come to Jackson’s defense. I defend him, not blind to his flaws and misdeeds, but because history takes a wider view.

There are no uniformly good and uniformly bad men of history. Every great figure in history was imperfect. Some of them made egregious moral mistakes, but these should never lead us to dismiss them completely.

In addition, it is worth knowing more about the context of their times and its influence on their decisions. To some, this may seem like a cop-out, but it does help give us greater understanding of historical figures.

Jackson lived in a time when America was a weak power surrounded by mighty European empires. The British, French, and Spanish encircled the American republic. At times, they incited Native American tribes against American settlers. Those tribes were, of course, threatened by the encroachment of white settlers.

A great objective of the American republic was to eliminate the threat posed by European empires in the Western Hemisphere. And this was no idle threat, evidenced by the British burning down our national capital in the War of 1812.

It was in this violent and dangerous world that Jackson acted to expel the European threat. To many Americans, the presence of Native Americans was related to that threat, as some tribes had previously allied with European powers.

While the means Jackson employed are fairly debated, it helps to know that he was not the sole sinner in a world of saints—it was a world of turmoil where the threat and use of violence was an essential tool used by multiple sides.

Even if one cannot accept context, Jackson made two undeniable contributions to the American people.

First, his victory in New Orleans in 1815 ensured, once and for all, that the British would not command the Mississippi, which could have endangered American possession of the Louisiana Territory (acquired under President Thomas Jefferson). It was wholly reasonable for Americans to want to eliminate the British threat to their territory.

Second, Jackson stood by the Union when it was threatened during his presidency in the Nullification Crisis. South Carolina, reacting to a highly protective tariff, threatened to void federal law. Jackson’s own vice president, John Calhoun, led the effort.

Some expected Jackson, a southern slaveholder, to fall in line. Instead, Jackson took a bold stand in favor of the Union. He threatened to use force to enforce the law—prefiguring Abraham Lincoln’s actions in the Civil War—but he also worked to negotiate a compromise.

Author Jon Meacham writes:

Had Jackson been truly unwilling to compromise, he would have found the means to use military force against South Carolina. He held back only when he chose to hold back. … He had an intuitive sense of timing that served him well, and this … never served America better than it did in the winter of 1832-33.

These actions helped to delay civil war in America. When it did come, Jackson’s actions helped fortify Lincoln’s position. In Lincoln’s words, “The right of a state to secede is not an open question. It was fully discussed in Jackson’s time and denied.”

Jackson biographer James Parton wrote, “Andrew Jackson was a patriot, and a traitor. … He was a democratic autocrat, an urbane savage, an atrocious saint.” Parton recognized that Jackson was a man of immense deeds and misdeeds.

Modern-day observers seem to care for only half of the story. One also has to wonder why the misdeeds of Jackson’s adversaries are rarely mentioned—why the scrutiny is directed largely toward American figures, and what biases this reveals.

If we define our historical figures only by their mistakes, then we miss the broader story. We miss some very real and significant achievements in our history.

We would know George Washington and Thomas Jefferson only for owning slaves, John Adams for the Alien and Sedition acts, Woodrow Wilson for purging African-Americans from the federal government, and Franklin D. Roosevelt for the Japanese internment.

On Jackson’s birthday this year, we do history greater justice when we remember both the savage and the saint.