The speaker at my high school graduation was my father, Justice Antonin Scalia.

Although he delivered a fine speech, he did not deliver the line I remember most vividly from that day—I did.

It was my responsibility to introduce him with a brief speech of my own. I told the assembled throng about my father’s personal life: his immigrant father, his schoolteacher mother, his marriage to Maureen McCarthy, their nine children (gasps from the crowd!).

I covered his degrees from Georgetown and Harvard Law School, his work for presidential administrations, his time as a law professor at the University of Virginia and the University of Chicago.

I may have mentioned in passing that he’d been nominated to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1986 and confirmed by the Senate, 98–0. I cracked a joke about him gaining an unparalleled knowledge of the Constitution from his eighth child (that would be me).

I felt pretty good about the performance as I came down the final stretch. All that was left was to say his name and shake his hand as he approached the lectern.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said, “please join me in welcoming Justice Anto—.” Suddenly my tongue swelled up, my mouth tightened, and I couldn’t control what either did as I heard myself mispronounce my own father’s first name. I don’t even remember how I mispronounced it, because I’ve never rewatched the speech.

At the time it felt like I turned his first name into a 10-syllable tongue twister. (For the record, he pronounced it “AN-tuh-nin.”)

If I remember correctly, my father began his speech by returning the favor, pretending to forget my name. At least I think he was pretending. It’s not easy remembering the names of nine children.

The rest of my father’s speech proceeded without incident, which was no surprise. Steve Martin once observed, “Some people have a way with words. Other people, um … not have way.” Dad had a way.

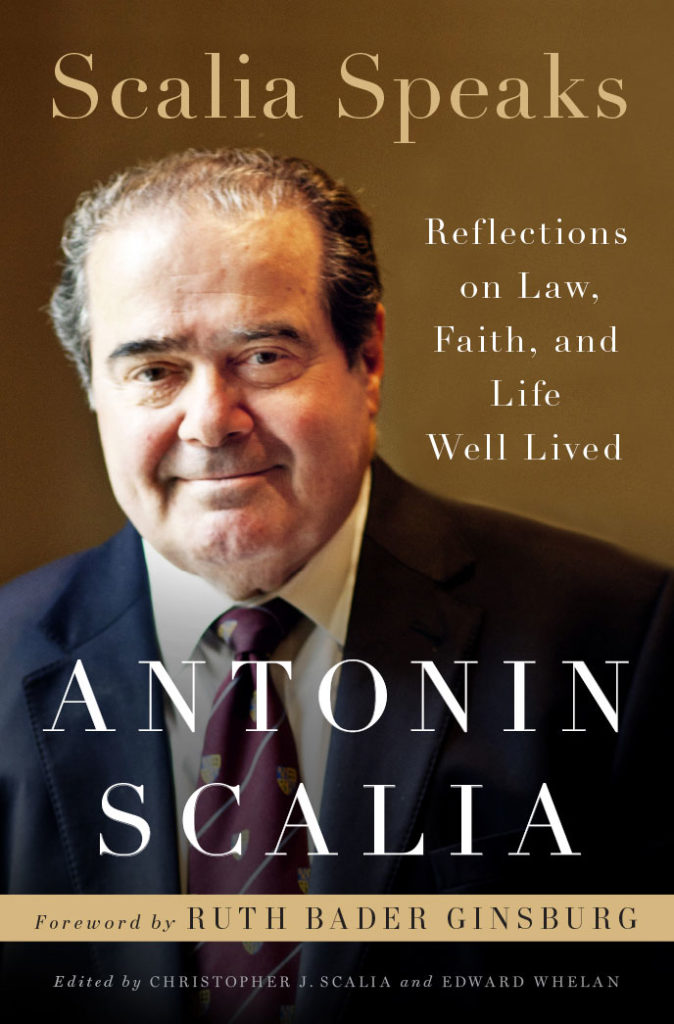

>>> Purchase Christopher Scalia and Ed Whalen’s edited book, “Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived”

Dad delivered hundreds of speeches over his career, around the United States and across five continents. He spoke to legal organizations, of course, and those speeches include some of the sharpest and most concise articulations of his legal philosophy.

These are speeches that lawyers still talk about, and that helped change the course of American jurisprudence.

Shortly after my father died, Neil Gorsuch recalled hearing him speak nearly 30 years before, “remember[ing] as if it were yesterday sitting in a law school audience.” One year after he shared that memory, Gorsuch filled my father’s vacancy on the Supreme Court.

But my father didn’t speak only to lawyers. And even when his subject was the law, his language was tailored to lay audiences in a way that his court opinions, as readable as they are, simply could not be.

Speeches also allowed him to reveal insights into his personal feelings and tastes in ways that legal opinions never can, or at least never should.

Of course, my father’s speeches were excellent in part because he was such a good writer. I once asked my father if writing was easy for him. “No,” he said. “It’s hard as hell.” That was a relief. If even he struggled with the craft, then maybe there’s hope for all of us.

There is also what he calls “writing genius,” which includes the ability to understand one’s audience. This isn’t the same as aiming to please.

He once gave my brother Paul some counterintuitive public speaking advice: “Never tell them what they want to hear.” Paul, who was deciding whether to study for the priesthood when my father said that, suspects that this was Dad’s way of telling him how to be a good priest.

Of course, Dad lived by this counsel, joking even before he was on the Supreme Court that the “endearing quality of saying the right thing at the wrong time is the secret of my popularity.”

My father’s approach wasn’t contrarianism for its own sake. The point was to challenge listeners out of complacency, to inspire them not by affirming what they knew to be true, but by provoking them into reconsidering their preconceptions. It was the public-speaking equivalent of the Socratic method, which he applied as a law professor.

Dad’s speeches also provided a chance for him to perform.

My father was a ham. In his high school’s production of “Macbeth” his senior year, he played the title role. As an undergraduate at Georgetown, he was president of the student theater group.

Along with his friend Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in 1994 and again in 2009 he appeared as an extra in the Washington National Opera’s performance of Richard Strauss’s “Ariadne auf Naxos.” He sang and played the piano at parties and was one of the best story and joke tellers I’ve ever heard.

Giving speeches catered to those strengths and loves in a way that opinions never did. The charm and gregariousness that drew so many people—including ideological adversaries—to him are prominent throughout this collection.

Several months before my father died, I dropped by my parents’ house to borrow something. He was in the basement, watching an old western.

“Sit down,” he said from his recliner. “Join me for a cigar.”

It was a tempting offer, but I couldn’t. Besides, there would be other opportunities—I had just moved back to the D.C. area and would see him often.

“Take a cigar with you,” he said. I did.

Although reading through these speeches doesn’t quite make up for that missed opportunity to spend more time with him in what turned out to be his final months of life, it did make me hear his voice again in all its warmth, wisdom, and humor.

This adapted excerpt was taken with permission from “Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived” (Crown Forum, 2017). The book is a definitive collection of beloved Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s finest speeches, and covers topics as varied as the law, faith, virtue, pastimes, and his heroes and friends. Featuring a foreword by longtime friend Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and an intimate introduction by his youngest son, this volume includes dozens of speeches, some deeply personal, that have never before been published. Christopher J. Scalia and the justice’s former law clerk Edward Whelan selected the speeches.