COLEBROOK, N.H.—His left foot in a walking boot after surgery, Rick Samson, an independent-minded county commissioner in the northernmost part of New Hampshire, is behind the wheel of his pickup truck, describing how this region—“North Country” to locals—is used to going it alone.

“I run as a Republican, however I consider myself neither a Republican or Democrat, or conservative, or liberal—I am an American and that’s where it starts,” Samson, 70, says in a New England accent that reveals exactly where he’s from.

So it’s totally within character for the people of Coos County, whom Samson serves, to depend on themselves to overcome the county’s distinction as the place with the highest combined death rate due to drugs, alcohol, or suicide in all of New England.

Part 1 of 5: The Crisis That May Have Swung Voters From Obama to Trump

“This is how the North Country works: We are collaborative, it’s not territorial; we try to do the best that we can and spread it out because we have so little,” Samson says. “We don’t have a lot.”

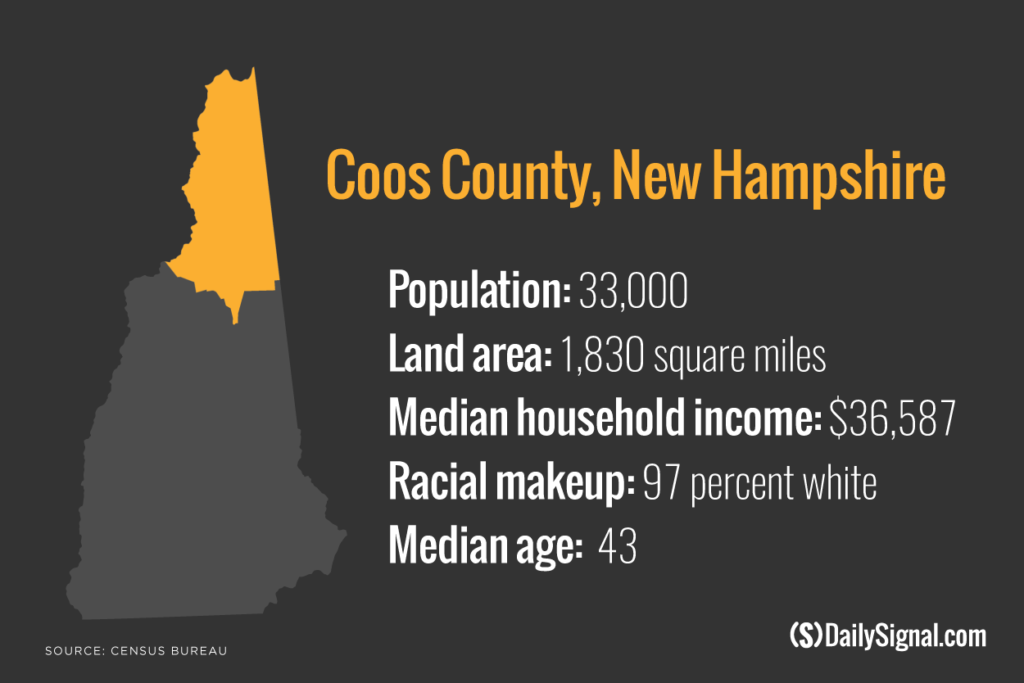

Coos County, part of “North Country,” the term locals use to define the northern third of New Hampshire, is the poorest in the state. The county is New Hampshire’s largest by area—1,830 square miles—containing numerous tiny towns spread far apart—and the smallest by population, with its 33,000 people representing less than 3 percent of the state.

Coos County has long had high rates of alcohol addiction. In recent years, though, opioids—mainly legally prescribed painkillers, but also the more potent and addictive heroin—have become the substance most abused.

Coos, like many other places in the U.S., is amid an epidemic of opioid overdoses.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioids—including prescription drugs as well as heroin—killed more than 33,000 Americans in 2015, more than in any previous year. Opioids now kill more people than car accidents; in 2015, more heroin deaths occurred nationwide than homicides involving guns.

New Hampshire has the second-highest drug overdose rate among all states, with 34 deaths per 100,000 residents in 2015.

Both of Samson’s parents were alcoholics, he says, and his youngest daughter’s husband died from alcoholism.

“I am very familiar with addiction,” Samson tells The Daily Signal as he speeds his truck deeper into the low fog hovering over a winding, deserted road, with few people and passing vehicles in sight.

Coos County also suffers from severe economic distress related to the loss of manufacturing jobs.

In 1980, manufacturing jobs comprised 38 percent of all jobs in Coos. In 2014, only 7 percent of jobs in the county were in manufacturing. Payroll wages from manufacturing have dropped from 49 percent to 9 percent since the mid-1980s.

“Life here is hard,” Samson says, pronouncing the word as hahd. “This area is so desperate for jobs, for anything, that [Coos residents] will do anything. You have nothing to do, so you are likely going to involve yourself in drugs and alcohol. This region has been decaying from within for quite a while. And hardly anyone notices.”

Rick Samson, a Coos County commissioner, says economic distress has fueled drug use. (Photo: Courtesy of Rick Samson)

Coos County, one of the nation’s most consistent swing counties, once found hope in Barack Obama, the Democrat from Chicago who voters easily re-elected as president in 2012.

Their hopes unfulfilled, a majority of Coos voters turned during the 2016 presidential election to another nontraditional politician promising change—billionaire developer and celebrity Donald Trump, running as a Republican.

Trump’s success in Coos County—he earned 52 percent of the vote, compared to Republican nominee Mitt Romney’s 40 percent in 2012—speaks to a little-discussed larger trend of the 2016 election involving rural parts of America and former manufacturing power centers.

A recent study by Penn State University showed Trump outperformed Romney most dramatically in counties where the drug, alcohol, and suicide mortality rate is among the nation’s highest. The mortality rate is defined as the number of drug-related, alcohol-related, and suicide deaths per 100,000 people.

Trump also won 18 of the 25 states that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said had the most drug overdoses in 2015.

Shannon M. Monnat, the Penn State study’s author and an assistant professor of rural sociology and demography, found that counties with high economic distress also have higher death rates related to substance abuse and voted strongly for Trump.

“Clearly there is an association between drug, alcohol, and suicide mortality and Trump’s election performance,” Monnat writes in her study, published in December, adding:

However, this relationship should not be interpreted as causal. No single factor can explain this election outcome. To suggest otherwise ignores the economic, social, and demographic complexities that drive human behavior and the contexts of the communities where these voters live. What these analyses demonstrate is that community-level well-being played an important role in the 2016 election, particularly in the parts of America far-removed from the world of urban elites, media, and foundations.

‘With You 1,000%’

Trump, like his general election opponent, Democrat Hillary Clinton, often repeated a campaign pledge to curb opioid abuse.

As the Republican nominee, Trump traveled to New Hampshire promising to combat the state’s opioid epidemic, which extends beyond Coos County.

This series:

Part 1: The Crisis That May Have Swung Voters From Obama to Trump

Part 2: One Opioid Addict Helps Another Choose Life Over Death

Part 3: ‘Dr. Father Pill’ Wants to Be Part of the Solution

Part 4: Police Assault on Opioids Gets Boost From a Family Doctor

Part 5: The First Responders Who Witness a Dreadful Toll

In 2015, more than 400 people in New Hampshire died as a result of drug overdoses, up from 326 such deaths in 2014 and 192 in 2013.

Trump, who finished first with 35 percent in the state’s crowded GOP primary field, said he would provide funding to local clinics to treat opioid abuse, and stop the flow of drugs coming into the state.

“I just want to let the people of New Hampshire know that I’m with you 1,000 percent, you really taught me a lot,” Trump said during a roundtable on the opioid crisis, where he met with residents affected by the drug epidemic and spoke of his own family’s history with addiction.

In interviews with The Daily Signal, Coos County voters say Trump’s promise of beating the opioid epidemic doesn’t explicitly explain his electoral success here.

Rather, Trump’s “America first” economic promise of bringing back manufacturing jobs from overseas, and renegotiating trade deals, was tailor-made for Coos, which has an aging population that is 97 percent white.

“I think people think as a whole that Trump will bring back manufacturing and get people back to work,” says Steve Cass, the chief of police in Colebrook, a town in Coos with 2,300 residents.

Cass says he usually votes Republican but doesn’t identify with a party.

“It was government that sold us down the river by basically allowing all these higher-paying production jobs to go overseas,” he says, “and maybe [residents] think it is government that can bring those jobs back.”

Karl Ruch, chairman of the Coos County Republican Committee, says few of his group’s 60 members—and other voters they interacted with—talked about response to the opioid crisis as a direct driver of their vote for president. But many, Ruch says, had personal encounters with addiction in some way.

Ruch, 60, was born and raised in Lancaster, a town of 3,500 and the county seat, where he worked for 20 years in the emergency room of a hospital, sometimes treating drug overdoses.

Karl Ruch, chairman of the Coos County Republican Committee, says President Trump’s promise to bring manufacturing jobs back has revived hope in the community. (Photo: Courtesy of Karl Ruch)

Health care and prisons (Berlin, Coos County’s only city, is home to both a state and federal prison) are the predominant industries today in the region.

The county routinely is ranked last in the state for the quality of public health, measured by indicators such as length of life, diet and exercise, income, access to housing and transportation, and drug and alcohol use.

Ruch says it’s intuitive that residents struggling through traumas—loss of a job or a home—could succumb to drugs and alcohol, and that solving those underlying problems could help curb their addictions.

“Trump’s message [gave] people the hope of bringing manufacturing jobs to the area again,” Ruch says, explaining:

When people thought about someone being able to re-energize manufacturing again, people also thought a lot of their other problems would be resolved. Trump may not have the exact answer, but there’s a ripple effect. If you have the economy growing, people after a long work day of logging or farming—true American jobs—want to go home and go to bed, and they don’t have time to get in trouble. They can have pride for themselves again, they can earn a paycheck and provide for their family.

In the 2012 general election, Obama won 57.9 percent of the vote in Coos County. (He also won the county in 2008, although Clinton beat him there in the primary.)

“The majority of people in Coos County do not like government,” Emily Stone Jacobs, the 34-year-old chairwoman of the Coos County Democrats, tells The Daily Signal. “But there is a lot of need in Coos County, and the people here responded to Obama’s message of hope and change.”

In addition to politics, Stone Jacobs works on the frontlines of the local opioid addiction crisis. She is a mental health counselor at Northern Human Services in Berlin, a nonprofit whose patients often have substance abuse issues.

Stone Jacobs attributes Trump’s success to Clinton’s unpopularity among Coos County voters.

“Coos County did not like Hillary Clinton,” Stone Jacobs says. “Trump winning here had mostly to do with Clinton being the nominee. I don’t think our drug addiction crisis had any influence on Trump winning.”

She notes that Trump did not set foot here during the campaign. The closest he came was a February 2016 stop in Plymouth, New Hampshire, a town in Grafton County bordering Coos to the south. Plymouth is about a two-hour drive from Colebrook.

By contrast, during the Democrats’ primary campaign, Bernie Sanders, the independent senator from Vermont, traveled to the county for a town hall in Berlin. With his plain-spoken style, Sanders ran on an economic platform similar to Trump’s, Stone Jacobs notes, and promised to boost funding for mental health and opioid addiction treatment.

Sanders earned 63 percent of the Coos County vote in the Democrat primary, beating eventual nominee Clinton by 28 points, the widest disparity of any county in the state. Sanders also earned a larger share of the total primary vote in Coos than Trump.

Once a ‘Great Place’

Coos County used to be a political destination and a tourist draw, says Samson, the county commissioner.

On a cold and dreary April morning, Samson is driving past what was once the Balsams Grand Resort and Hotel, an international hotel and ski destination that the federal government had listed on the National Register of Historic Places as worthy of preservation.

But the 400-room Balsams resort, a fortresslike compound surrounded by mountains and built on 11,000 acres—including a championship golf course—closed almost six years ago.

The hotel has major political symbolism: Every four years, residents cast ballots here at midnight in the first presidential primary votes in the nation. Ronald Reagan and both George Bushes made pitches to voters at the hotel.

In 2016, the first-in-the nation voting tradition continued, but in a hotel with no residents. Only Ohio Gov. John Kasich, a Republican presidential candidate, made it up here.

Today, the hotel’s various buildings stand intact, except for a dormitory for employees, which is partially—not all the way—torn down, as if frozen in time.

Samson, who has spent his entire life in Coos County besides a five-year stint in the Navy, recalls wistfully that his son and two daughters once worked at the 150-year-old hotel.

His children served food, but often smelled rubber, Samson says. That’s because the original owners of the hotel, the Tillotson family, ran a rubber factory on adjacent property.

The Tillotson Rubber Co., credited with creating the first latex balloons and gloves, shuttered in the 1980s, swallowed by overseas competition. An empty plot of melting snow marks its former existence.

“This is not the way this place always looked,” Samson says. “Balsams used to be known as ‘Switzerland of America.’ Between 1895 and 1905, Berlin was the largest paper-producing city in the world. It was a great place to raise a family.”

Balsams Grand Resort and Hotel closed almost six years ago, but still stands partially intact today. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

The fate of Coos County has regional consequences.

Coos is one of only two counties in the U.S. to border two states—Vermont and Maine—and another country, Canada.

One of the region’s largest employers, the furniture manufacturer Ethan Allen just over the Connecticut River—which marks the border—ceased production in Beecher Falls, Vermont, in 2009, putting about 250 people out of jobs.

The county’s once-dominant paper industry is in sharp decline, if not gone altogether.

Berlin used to draw labor from all over Europe to work in its paper mills. But Berlin has seen its population decrease to about half the peak of more than 20,000 in the 1930s.

‘Getting the Boot Down’

Cass, Colebrook’s police chief for the past 13 years, says local residents have learned not to expect much help from politicians.

“We don’t get the help from the outside and we don’t rely upon them, either,” says Cass, 48, whose matter-of-fact way masks his jolly demeanor.

Cass, born and raised in Coos County, is taking it upon himself to spend a day on patrol.

Colebrook Police Chief Steve Cass sometimes does patrols to supplement his nine-officer force. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

His nine-officer police department (only five are full time) is housed inside Colebrook Town Hall, which also hosts the tax collector, town manager, and district court.

Cass begins his shift driving his unmarked SUV through the Windsor Estates trailer park—an unfitting name for a cluster of mobile homes where residents are all low-income and white.

A “large percentage” of calls to the police in Colebrook come from the trailer park, Cass says, mostly related to domestic disturbances and opioid misuse.

“This right here is an example of what’s becoming Colebrook and Coos County,” Cass says of Windsor Estates. “This area has been getting nothing but getting the boot down, just getting stomped on. Jobs have not come back, nothing has regenerated, and what we get is politicians saying they know the plight of North Country, and Coos County, but nothing changes.”

The police department, Cass says, makes only a few arrests a week and a little more than 100 in a year. But in a small town like this, the impact of crime is closely felt, and its origins easy to trace.

“Most our crime is related to the use and sale of drugs,” Cass says. “The opioid problem for us started at the prescription level. Let’s face it. When it comes down to it, we put ourselves in the position we are in because of overprescribing. It’s coming from within.”

‘Part of the Problem, Part of the Solution’

Coos County’s opioid epidemic mirrors America’s. It started with doctors prescribing pain medication such as oxycodone or methadone for legitimate reasons.

From 1999 to 2013, the amount of opioids prescribed in the U.S. nearly quadrupled, the CDC says, and today about 2 million Americans are addicted to them.

Opioid pain relievers generally are safe when taken for a short time as prescribed by a doctor, but because they produce euphoria as well as pain relief, they can be misused. Prolonged use can increase the risk of addiction, overdose, and death.

In Coos County, on-the-job injuries are common, and popular recreational activities—thrill rides through the mountains on ATVs and dirt bikes—can be dangerous.

“This is a playground up here,” says Laurie Connors, director of behavioral health services at Indian Stream Health Center, the largest health care provider in Coos. “The mentality ‘Live Free or Die’ [New Hampshire’s official motto] does explain a lot.”

Coos County, a place known for its outdoor recreation and natural beauty, borders Canada to the north, Vermont to the west, and Maine to the east. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Indian Stream Health Center is one of 11 federally qualified health centers in New Hampshire, meaning it provides comprehensive services—primary care, dental, mental health—to an underserved area. This designation also means it qualifies for federal funding and enhanced reimbursement for Medicare and Medicaid.

Because the center offers services for all kinds of care—to about 4,000 patients per year, regardless of ability to pay—Indian Stream doctors prescribe more medication than any other provider in the area.

Jonathan Brown, Indian Stream’s CEO, acknowledges that his center was part of the problem, as doctors responded to demand for pain pills from low-income residents who couldn’t afford alternative services for pain, such as physical therapy.

“You’d have to go back decades when pain became a vital sign and the pharmaceutical industry began influencing prescriptions of these medications as the end-all be-all, and how delivering that medication impacted patient satisfaction surveys, which affects our reimbursement,” Brown says in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“A patient comes in with pain and the provider says, ‘I will give you five days [of medication], but then I need you to stretch and do your exercises and change your lifestyle.’ Patients aren’t doing that. They want the quick fix. They want the pill.”

In response to the trend of overprescribing, the state of New Hampshire in January implemented new protocols requiring medical professionals to conduct a risk assessment before prescribing opioids.

Patients also must sign an informed consent form, which allows doctors to access a database in the state’s prescription drug monitoring program to ensure the patient isn’t seeking drugs from multiple doctors. The form describes the risks of overdose and addiction, and requires the patient to submit to random pill counts to ensure he or she is taking the prescribed amount of medication.

Indian Stream is taking these regulations a step further, requiring patients who receive prescription pain medicine for 28 days or longer to participate in treatment at the facility, such as a substance abuse class or group therapy.

“We have the self-awareness to be honest with ourselves to say, ‘We have been a part of the problem, and we have to be a part of the solution,’” Brown says, adding:

And it’s wrong to say prescription opioids are bad. It’s more appropriate to say the misuse of those opioids are bad. Our responsibility is to educate, inform, and raise awareness for how to safely use prescription medication, how to keep our children safe, and how to teach our children to live healthy lifestyles. We are lucky enough to be in a position to do God’s work, and this organization provides a vehicle for us to do that. And we will.

A New Drug That’s ‘Killing People’

As prescriptions have become more tightly regulated, and there is less supply of cheap opioid pain pills on the street, increasingly addictive drugs such as heroin and fentanyl have replaced them.

These illicit drugs come from outside Coos County.

Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid mostly used in medical settings to relieve pain related to cancer, is especially worrisome to local law enforcement officials. Fentanyl is often manufactured illegally for nonmedical use, and is frequently found as a street drug mixed with heroin.

According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, it usually originates from China and is sometimes trafficked directly into the U.S. or through Canada.

Carfentanil is one of fentanyl’s many analogs. It is typically used as a tranquilizer for large animals such as elephants, and it can kill people exposed to even tiny amounts.

According to the CDC, the fraction of drug overdose deaths across the nation involving synthetic drugs such as fentanyl rose from 8 percent in 2010 to 18 percent in 2015.

From 2014 to 2015, heroin overdose death rates in the U.S. increased by 21 percent, with nearly 13,000 dying in 2015.

“It’s easy to say the opioid crisis is a problem of legal prescription drugs,” Seth Leibsohn, co-director of Americans for Responsible Drug Policy, says in an interview with The Daily Signal.

“But most of the deaths of late are not happening that way,” adds Leibsohn, a former chief of staff to William Bennett, who served as “drug czar” under President George H.W. Bush. “Deaths from prescribed opioids are a problem, but the majority of deaths from those come from the diversion and illegal distribution of them.”

John McCormick, Coos County attorney, says the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl has become the predominant killer in the community. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

John McCormick, the Coos County attorney and chief law enforcement officer, says that in 2015, five overdose deaths in the county resulted from the use of fentanyl. Last year, fentanyl killed three people here.

“Fentanyl is what’s killing people,” McCormick says quietly, sounding almost resigned to this fact in an interview with The Daily Signal in his office, where soft jazz plays in the background.

“The goal for overdose deaths in the county should be zero. We don’t want any people dying. Is it possible? I don’t know. In this climate, probably not right now.”

‘Got to Save Kids’

With the opioid crisis here evolving, and already having victimized the working class, local leaders are turning to protect the next generation—or at least what’s left of it.

Cass, the Colebrook police chief, says a recent graduating class of the high school in Pittsburg—the northernmost town in all of New Hampshire—had one student.

The town, part of Coos County, has fewer than 1,000 residents.

“Imagine that—that boy is the salutatorian and valedictorian all in one,” Cass says facetiously.

“Most of our adolescents who graduate, they move on,” he adds, noting the example of his own three children, all of whom graduated from Coos County schools but plan to find work outside the region.

Main Street in Colebrook, a town in Coos County with 2,300 residents (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

The public school district in Berlin, serving 1,200 students in four schools, has taken especially aggressive action to guard against opioid abuse among the youth.

Corinne Cascadden, Berlin’s relentlessly upbeat superintendent of schools, says she currently knows of six to eight students who are active drug users.

In 2013, almost 6 percent of Berlin High School students admitted trying heroin at least once, according to a CDC survey. The New Hampshire average for heroin use among high school students is 3 percent.

Last year, the Berlin school board made the anti-overdose drug Narcan available in the nurse’s office at all schools. The drug, a nasal spray that instantly can reverse an opioid overdose, has not had to be used on a student yet, Cascadden says.

The school district is also in its third year of participating in Project AWARE (Advancing Wellness and Resilience in Education), a mental health program for students funded with federal grant money.

Bob Thompson and Corinne Cascadden of Berlin Public Schools have taken aggressive action to guard against opioid abuse among the youth. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

Through the program, teachers, principals, sports coaches, and others are taught how to recognize and respond to mental health issues. Those trained adult leaders can refer students to a mental health counselor inside the school if they meet certain risk factors, such as academic failure, aggressive behavior, and family problems at home.

As of April, about 140 students were being served through the program, which is voluntary since parents may opt not to have their child participate.

“The upside and downside of being a small district is students are known, their behaviors outside of school are known, who they associate with are known, their families are known—often by our staff who have been born and raised in this community,” says Bob Thompson, the school district’s Office of Student Wellness coordinator.

“We are reading the names of the parents of these students in the local paper, or in the police report, for drug and alcohol use. They are growing up in that environment.”

Thompson says he knows of some parents of high school students who use their children to sell drugs to feed their own habits.

The cycle of addiction is literally built inside some Coos County children from birth.

The Androscoggin Valley Hospital, Berlin’s only hospital, reports that 10 percent of children born there are addicted to drugs.

“You can impact students one at a time,” Thompson says, adding:

That’s not to say some of them aren’t already lost. Because we know some of them are. We will not be able to turn around all of those users. It’s important we try, because eventually these students are out in our community and they are either going to be assets or liabilities. We are going to have our police department chasing them around town, and they will be clogging our judicial system, and not being productive members of society, or they will be assets and productive members of society.

Cascadden, a county native who is in her ninth year as superintendent, is invested in this community’s survival.

Her own children went through her schools when she was a principal in the district for 23 years.

She is such a fixture that she says parents sometimes call her to come to students’ homes and get them out of bed and drive them to school.

On these full-service missions, Cascadden has in certain instances seen signs of drug use in the home.

It may seem out of place for a school superintendent to play parent and chauffeur, wandering into homes and taking charge, but then again, what if nobody else is there to solve the problem?

“There is lots of resiliency in this community,” Cascadden says. “You know, we are not afraid to say we have a problem. I mean, we have a drug problem. Why say everything is fine? It is not. But the other piece of that is, OK, what are we going to do about it? Because we are used to solving our own problems, and we are going to make it work because we’ve got to save kids.”

Next, in Part 2: In New Hampshire’s poorest county, one opioid addict helps another choose life over death.