This month of each year, we commemorate the great individuals and events in the history of African-Americans.

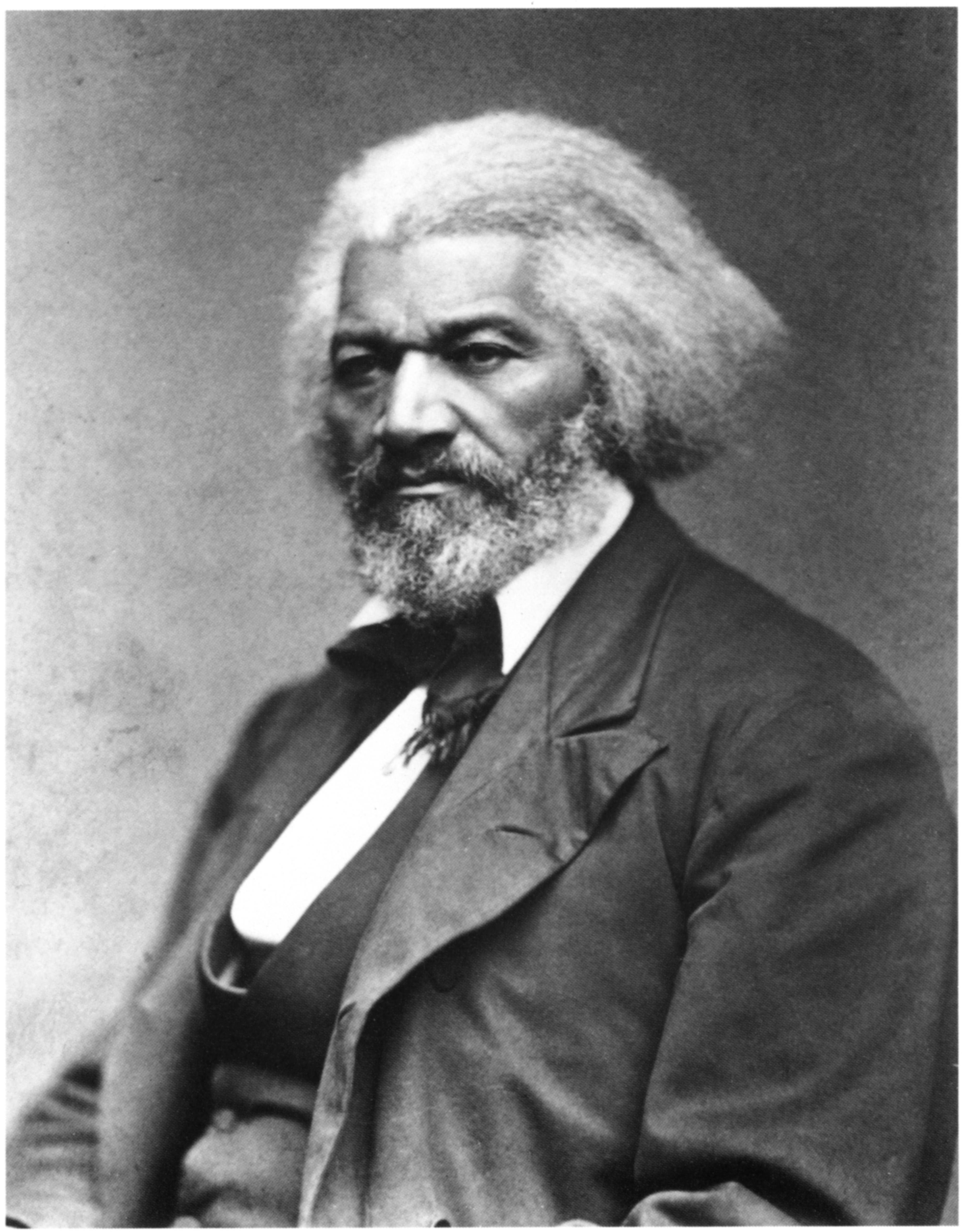

On Tuesday, marking his 199th birthday, we will commemorate perhaps the greatest of them all, Frederick Douglass—a singular exemplar and apostle of the American spirit.

“He was an American of the Americans,” Douglass once said of Abraham Lincoln, in words that apply no less aptly to himself. “Born and reared among the lowly, a stranger to wealth and luxury, compelled to grapple single-handed with the flintiest hardships of life … he grew strong in the manly and heroic qualities demanded by the great mission to which he was called.”

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

Douglass loved America. He loved it for its principles and for its promise. Nonetheless, the sentiment of patriotism, which he regarded as “pure, natural, and noble,” did not come naturally or easily to him.

“What country have I?” he asked in an 1847 editorial, and he then answered: None. As he confessed to his early abolitionist mentor William Lloyd Garrison, the sentiment of patriotism “was whipt out of me” by the slave masters under whose dominion he was born.

Given the circumstances of his youth, it is unremarkable that Douglass, after escaping from slavery, would embrace the teaching of Garrison, who in his abolitionist zeal rejected the Constitution as a pro-slavery “covenant with death” and who would call for non-slaveholding states to sever their association with slaveholders by seceding from the federal union.

What is remarkable is that within a few years, by conscientious study and reflection, Douglass set himself on a different course.

Douglass came to reject the Garrisonian position, and he explained why in a Fourth of July oration delivered July 5, 1852, a speech now recognized as the greatest of all abolitionist speeches.

In it, he praised the Constitution as “a glorious liberty document,” and he extolled the Founders for their courage and their wisdom alike: “They were brave men. They were great men too. … They seized upon eternal principles, and set a glorious example in their defense. Mark them!”

In those principles—the principles of the Declaration of Independence—Douglass found the distinctive promise of America.

“The leading object of [our] government,” Lincoln said in a July 4 message of his own, is “to elevate the condition of men—to lift artificial weights from all shoulders—to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all—to afford all an unfettered start, and a fair chance.”

Precisely so, Douglass added in the most popular of his post-Civil War speeches:

America is said, and not without reason, to be preeminently the home and patron of self-made men … [The] principle of measuring and valuing men according to their respective merits and without regard to their antecedents, is better established and more generally enforced here than in any other country.

Douglass summarized the nation’s promise a few years after the Union victory. America’s mission, he proclaimed, is to become “the most perfect national illustration of the unity and dignity of the human family that the world has ever seen.”

The converse is still more telling: As Douglass conceived of the virtue of the country in terms of human integration and elevation, he conceived of the main dangers to it as forces of disintegration and degradation, including any and all artificial barriers to the exercise of individual rights and the cultivation of civic unity.

Those forces and barriers were manifold. In the antebellum period, they included not only slavery itself but also Garrison’s disunion proposal, in which Douglass found “no intelligible principle of action.”

Both before and after the Civil War, they included also the ideas of constitutional state sovereignty and of sectionalism whereby portions of the country were licensed to disregard rights proper both to human beings and to American citizens.

“The true doctrine,” Douglass wrote in objecting to the Supreme Court’s Slaughter-House Cases doctrine of differential state and federal citizenship rights, “is one nation, one country, one citizenship and one law for all the people.”

Most powerful of all sources of disintegration, however, was race. Beyond his objections to race-based slavery, needless to belabor here, of particular interest is Douglass’ objection to the cultivation of racial identity even when the aim was racial uplift rather than oppression or exclusion.

A few months before he died, he observed, “We hear, since emancipation, much said … in commendation of race pride, race love, race effort, race superiority, race men, and the like.”

Conceding that what he had to say “may be more useful than palatable,” he nevertheless admonished the friends of racial equality that they:

make a great mistake in saying so much of race and color … It is an effort to cast out Satan by Beelzebub … I would place myself, and I would place you, my young friends, upon grounds vastly higher and broader than any founded upon race or color … Not as Ethiopians; not as Caucasians; not as Mongolians; not as Afro-Americans, or Anglo-Americans, are we addressed, but as men. God and nature speak to our manhood, and to our manhood alone.

Douglass’ story is the story of an American who, like his country, rose from a low beginning to a great height, who gained freedom by his own virtue and against great odds, and who matured into a world-famous apostle of universal liberty.

It is the story, too, of a man divided by race, who with time and work became his country’s most prominent representative of the aspiration toward racial uplift, reconciliation, and integration.

Recounted in three finely crafted autobiographies, Douglass’ story is timely in any season and locale.

In our own, a time when many Americans feel trapped by circumstances, ignored, or disdained by those in positions of public responsibility and confused about the meaning and merits of their country’s identity, it is particularly so.