Tom Price took the helm of the Department of Health and Human Services on Friday, capping a lengthy confirmation process that ended in the wee hours of the morning.

Now, as the health and human services chief, Price can begin fulfilling a yearslong goal of unwinding Obamacare. But instead of dismantling the health care law from the halls of Congress, he’ll be acting from inside the agency that oversaw its implementation.

The Senate confirmed Price 52-47, and the former House Budget Committee chairman is taking over the Department of Health and Human Services as the White House and Congress prepare to follow through on their campaign promises to repeal Obamacare.

An orthopedic surgeon who served more than a decade in the House, Price has spent the last seven years in Congress opposing the Affordable Care Act. The new HHS secretary introduced his own health care plan in 2009—he’s reintroduced that same proposal, the Empowering Patients First Act, in every Congress since then.

The Georgia Republican will take the helm of the agency at a crucial time. GOP lawmakers are debating how to dismantle the law, with a vote to repeal the Affordable Care Act expected to take place by March or April.

Unwinding Obamacare

But even as congressional Republicans finalize their course for unwinding the law, Price can now use his executive power to begin chipping away at Obamacare’s framework.

The Affordable Care Act gave the federal government the power to write and implement many of the law’s regulations through the federal rule-making process—like the exemptions from the individual mandate that are available to consumers who encounter hardships and the mandate that requires insurance plans to cover contraception and abortifacients.

And already, President Donald Trump is using that authority to make changes to the law.

“You live by the administrative state, you die by the administrative state,” Ed Haislmaier, a senior fellow at The Heritage Foundation who worked on health policy for Trump’s transition team, told The Daily Signal.

During a confirmation hearing in January, Price told a Senate committee he believed insurers needed some assistance from the Trump administration before 2018.

“What they need to hear from all of us, I believe, is a level of support and stability in the market,” the Georgia Republican said.

And as the new health and human services secretary, Price can begin providing them with that relief by tightening the monitoring of consumers purchasing coverage on Obamacare’s exchanges—changes insurers asked the Obama administration to make long before Trump took office.

That includes making changes to special enrollment periods, or the time outside the standard enrollment window a person can purchase health insurance, and verifying the eligibility of consumers purchasing coverage during open enrollment and special enrollment periods.

The Obama administration created several special enrollment periods, which a consumer can qualify for if they lose their health insurance, get married, or move to a new state.

But insurance companies warned last year that Americans were taking advantage of the special enrollment periods and purchasing coverage only when it was needed.

That led to an increase in costs for plans and higher costs for consumers, insurers said.

“The Trump administration you would expect to go in and say, ‘We’re going to prioritize minimizing costs and disruption, and we’re not going to let people enroll at the drop of a hat,’” Haislmaier said.

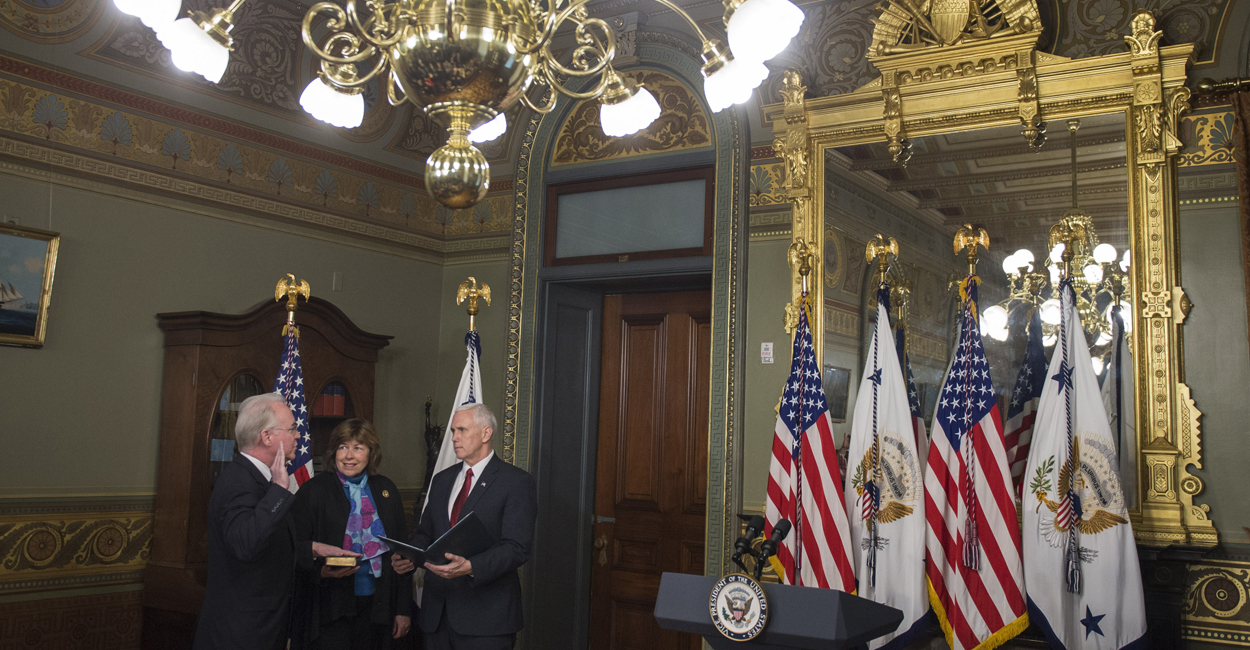

As the new secretary of health and human services, Tom Price can begin making changes to the Affordable Care Act, even before Congress acts. (Photo: Pat Benic/UPI/Newscom)

The new health and human services secretary can also eliminate federal regulations that already exist at the state level, such as oversight over proposed rate increases and network adequacy.

Under the current system, insurance companies looking to raise their rates must receive approval from state regulators and the federal government, which review the plans insurers want to sell for the upcoming benefit year.

“If you’re approaching it from the Obamacare mindset, then you make insurers go through all of that at the federal level after they’ve done it at the state level,” Haislmaier said. “If you come in at the Trump administration, they’re saying, ‘We’re not interested in nationalizing insurance. If it’s OK with the state, it’s OK with us.’”

According to draft documents obtained by Politico, the Trump administration is also weighing whether to make changes to a provision of Obamacare that dictates how much more insurers can charge older Americans than younger Americans.

The provision prohibits insurance companies from charging their older customers more than three times what they charge younger customers. According to the documents, the Trump administration proposes changing the ratio to 3.49-to-1.

Health policy experts, though, worry that such a change may not be legal, since the Affordable Care Act specifically set the ratio for insurance companies. Changing the ratio from 3 to 3.49 would require action from Congress.

Still, Trump administration officials believe that since 3.49 “rounds down” to 3, the changes can be made without a change in statute, according to The Huffington Post.

Eliminating Mandates

In addition to enhancing the monitoring of consumers who sign up for coverage, Price can take aim at one of Obamacare’s most controversial provisions: the contraception mandate, which requires plans to cover contraceptives and abortifacients without cost-sharing.

Price, an opponent of abortion, has criticized the contraception mandate in the past for infringing on religious liberty.

As the leader of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Georgia Republican could have his agency rewrite the regulations tied to the mandate or choose not to enforce it.

Price could also revise the list of services insurers are required to cover—called the essential health benefits requirement—to amend or exclude preventive health.

The White House set the stage for the new Health and Human Services secretary to begin making changes to Obamacare just hours after the president took the oath of office.

On Inauguration Day, Trump signed an executive order to “ease the burden of Obamacare as we transition to repeal and replace.”

The order was light on specifics, but health policy experts said it gave the executive branch the authority to begin addressing the thousands of regulations tied to Obamacare.

And some wondered if the individual mandate was on the chopping block.

Price could decide not to enforce the individual mandate, the part of Obamacare that requires consumers purchase insurance or face a fine, or extend hardship exemptions to all enrollees.

But Haislmaier said that for Price, the decision regarding enforcement of the mandate would need to involve the White House, since such a move would require coordination between multiple agencies.

For the executive branch, deciding whether to enforce the individual mandate also is a game of timing.

Republicans are considering passing a repeal bill that gets rid of the individual mandate, among other major provisions of Obamacare.

Turning to Congress

Haislmaier questioned whether it would be necessary for the Trump administration to take action on a part of the law Congress may get rid of on its own.

“If the mandate is going to be repealed in repeal legislation, is it worth the bother of the administration doing it?” Haislmaier asked.

Like with the executive order on Obamacare, the White House began the process for making changes to the health care law through the rule-making procedure before the Senate confirmed Price.

Last week, the Trump administration submitted a proposed rule to the Office of Management and Budget. The details haven’t yet been released to the public, but the rule aims to stabilize the Obamacare markets, likely through the changes reference above.

Once the details are released, it’s Price who will oversee the efforts to provide relief for insurers.