As police around the country grapple with recent violence against their own, Chief Brandon del Pozo of the Burlington Police Department in Vermont is requiring his officers to pair up when responding to calls for service, as a method for added safety and support.

“It’s important for cops to have someone to talk to about what’s going on instead of stewing in a car alone for hours,” del Pozo told The Daily Signal in an interview. “Tense and uncertain environments stop cops from slowing things down, problem solving, and listening to citizens. Just having a partner on hand to process what’s going on will help us return to normalcy.”

Other police departments that are implementing two-person patrols include San Diego, Los Angeles, Oakland, Boston, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, another big city agency, the City of Orlando Police Department, is looking into purchasing bullet-proof vests designed to repel sniper fire in a way that normal protective gear can’t.

“It’s just hard for us, especially the past few years, where we’ve seen more ambush style shootings,” Orlando’s police chief, John Mina, told The Daily Signal in an interview. “Here in Orlando, we have a pretty rich history of engaging with the community and we aren’t afraid of doing that. Though morale is good, we are telling officers to be super vigilant, everywhere.”

John Mina, the Orlando police chief, says it is a “hard balance” for officers to maintain community relations while also being more vigilant in the wake of recent violence targeting law enforcement. (Photo: Carlo Allegri/Reuters/Newscom)

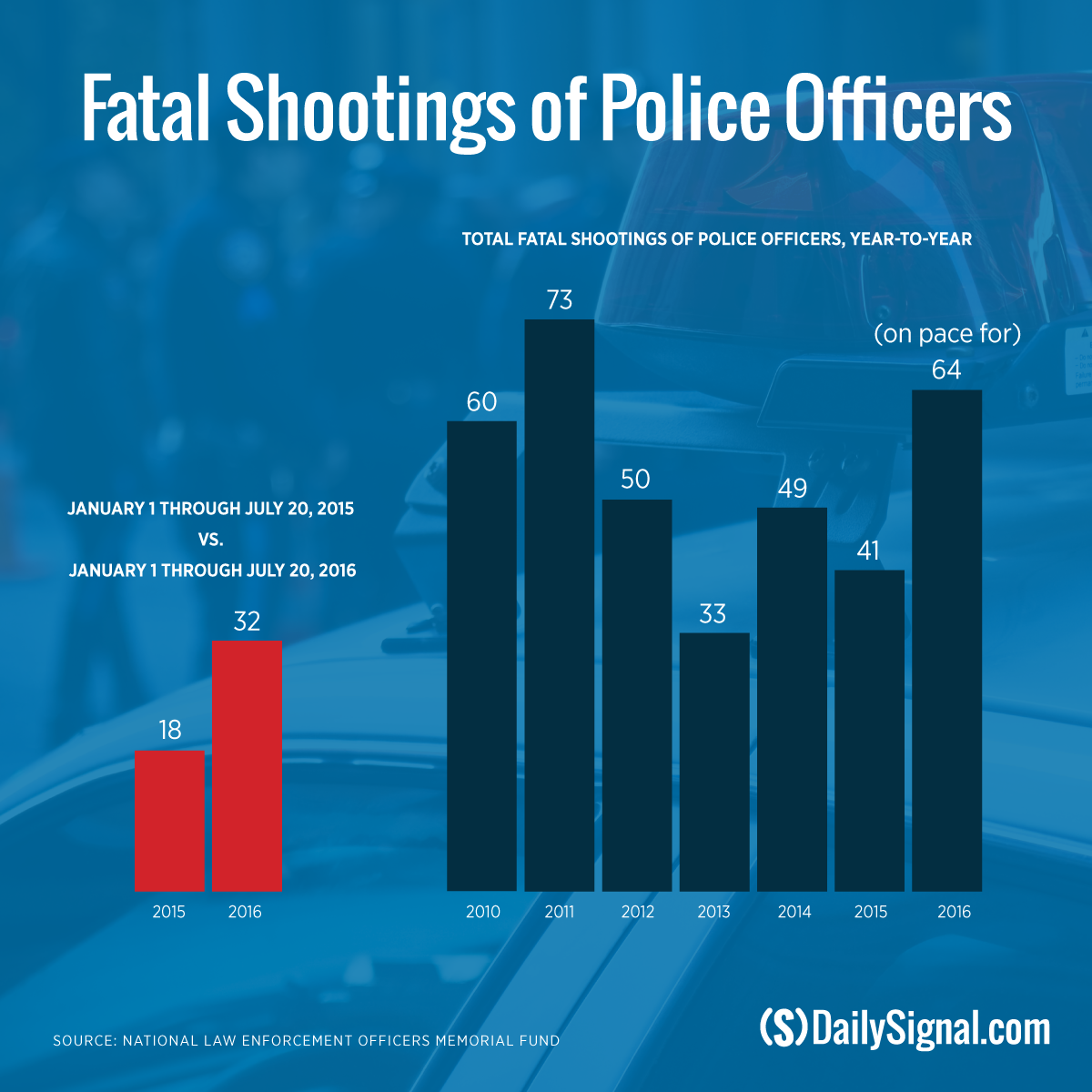

In interviews with The Daily Signal, law enforcement leaders across the country caution that the fatal shootings of police officers mounting this year are forcing at least a short-term change in law enforcement tactics, and causing anguish among families of police who worry about the people they care for risking their lives on the frontlines.

Yet at the same time, police departments are responding to recent ambush attacks in Dallas and Baton Rouge that left eight officers dead by mostly taking the long view, emphasizing the importance of shoring up community ties as a way to diffuse historic tension around law enforcement.

>>>Why Police Say Body Cameras Can Help Heal Divide With Public

“Community policing has to continue because it’s the right way to police our communities,” says @BrandondelPozo, the Burlington police chief.

“Community policing has to continue because it’s the right way to police our communities,” said del Pozo, who polices a predominantly white city experiencing the opioid crisis and violence associated with it. “But my officers have to feel safe before they can connect with citizens. They know that in Vermont we feel a little lucky to have it better than Missouri, or Louisiana, or Minnesota, but we know sometimes there is no logic behind where violence can strike.”

‘Easy Targets’

While larger police departments have the manpower to take extra precautions, and can still maintain quick response times across the areas they cover, other smaller agencies are not changing their tactics because they can’t afford to.

Mark Wasylyshyn, the third-term Republican sheriff of Wood County, Ohio, has not been able to double up patrols in the sprawling rural area policed by his 125 deputies.

He recognizes how police officers are particularly vulnerable to ambush-style shootings, even though the mostly white county he represents is far removed from the tension that exists in more urban cities.

“If someone wants to kill us, we unfortunately are easy targets,” Wasylyshyn told The Daily Signal in an interview. “If someone really wants to kill a cop, they can call 911 and tell us where to be. But while we always have to be vigilant, we are very engaged with our community and I truly believe most people are really good and appreciate their local law enforcement. There are a very small amount of people who want to do us harm.”

Even though Wasylyshyn doesn’t have the flexibility to institutionalize two-person patrols formally, he says deputies always have the option to radio in a request for a second deputy to assist a scene.

The sheriff’s department is also taking other actions to handle mass protest situations, even though there have been few in Wood County.

A mobile field force made up of representatives of area law enforcement agencies, including the police representing the nearby Bowling Green State University, convened for the first time on Monday with the mission of training officers how to maintain peace in situations of civil unrest without imposing on freedoms.

“I truly believe most people are really good and appreciate their local law enforcement,” says @woodctysheriff.

“A lot of problems arise with law enforcement not knowing how to respond to an incident of unrest,” said Eric Reynolds, the chief deputy of Wood County Sheriff’s Office. “When we have officers make mistakes, we discipline them and take care of business. As long as you do that, and focus on training officers the right way, the community appreciates it and doesn’t judge all law enforcement by that one misdeed.”

‘Public and Police Together’

Capt. Marc Yamada of the Montgomery County Police Department in Maryland is tasked with reiterating the community-first approach that has come to define modern policing.

It’s a counterintuitive idea, to engage after you’ve been wronged, rather than withdraw — to walk through neighborhoods as a matter of routine, instead of just in response to an emergency.

Capt. Marc Yamada of the Montgomery County Police Department in Maryland says the “public and police together” will overcome recent violence against law enforcement. (Photo courtesy of the Montgomery County Police Department)

But this is the way Yamada is telling his fellow officers to respond — including his son, Ryan, a recent college graduate and once-aspiring accountant who chose the most contentious of times to instead join Montgomery County’s police academy.

“While yes, the current events are extremely negative in nature, it just strengthens our belief in community policing,” said Yamada, director of community outreach for the police, a recently created position in the department.

“It’s the public and the police together,” Yamada told The Daily Signal in an interview. “If they trust us and see and know you, they are our first line of defense. The community sees and hears things before we do, and promoting an environment that makes them comfortable enough to just call us leads to prevention and detection of criminal activity.”

‘It’s a Philosophy’

Margaret Mims, the 10-year sheriff of Fresno County in California, says her agency has earned the respect of the community.

In the past five and a half years, she says, the sheriff’s office has had 11 officer-involved shootings out of 1,220,000 calls for service.

The agency trains its 430 deputies on developing verbal de-escalation techniques before resorting to force.

In addition, she says, the sheriff’s office meets regularly with representatives of Fresno County’s minority communities, especially its large hispanic population.

“Their concern is they feel they are being targeted by police, and law enforcement’s perspective is when we need you, you need you to help us,” Mims told The Daily Signal in an interview.

Her community is returning the favor, letting their police know that they have law enforcement’s back.

The day after the fatal shooting of police officers in Dallas, Mims walked upon a sign posted on the gate outside of a sheriff’s office substation that read, “We Support Our Deputies.”

God Bless the citizens who placed this sign of support on the fence of one of our FCSO substations! pic.twitter.com/cehFRJ8fvM

— Margaret Mims (@MargaretMims) July 8, 2016

Mims, a Republican who serves a conservative region of a liberal state, credits this mutual understanding to an agency-wide dedication to community policing.

“I believe that law enforcement did get away from remembering that they serve the community, and that’s why we are seeing such tension,” Mims said.

“I think other law enforcement agencies made community policing too difficult by trying to assign it to a specific unit within the department,” Mims added. “If you have a special unit, you have members of the broader agency saying, ‘I don’t have to do that. It’s up to them.’ It’s not a unit or program. It’s a philosophy that has to thread its way through the whole organization.”

“Law enforcement did get away from remembering that they serve the community, and that’s why we are seeing such tension,” says @MargaretMims, the Fresno County sheriff.

Mims was born and raised in Fresno County. During her 36 years in law enforcement, she’s experienced lows and highs of police history. She observed the Rodney King riots of 1992, and has obtained numerous awards recognizing her shattering of glass ceilings as a woman police professional.

Today’s and tomorrow’s officers have a chance to define this unique period in policing, Mims says, and she encourages them to approach that task in a positive way.

“Here is what I tell groups who want to become law enforcement: If you want to do it because you want to drive a patrol car, have a gun, and a wear uniform, do something else,” Mims said. “That’s all part of it. But the number one thing is you have to have the heart of wanting to serve the community.”

‘Volatile Situation’

Despite law enforcement’s efforts to continue best practices, and enhance training, some observers worry that these proactive efforts are easier said than done in this fragile moment in police-community interactions.

“There is a period of time when cops are human and they are going to be responding to some situations differently, so you’re not going to be as proactive perhaps in some cases, and that could impact certain kinds of activities,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a research organization in the District of Columbia.

Heather Mac Donald, a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and author of the forthcoming book “The War on Cops,” argues that officers are policing more cautiously due to criticisms they’ve received following recent high-profile officer shootings of black men.

She attributes last year’s spike in murder rates in many U.S. cities to what she views as a backing off from “proactive policing.”

“If you are an officer, you are walking into a very volatile situation right now,” Mac Donald told The Daily Signal in an interview. “Officers are human, and if they are taunted and jeered and decide to back off, criminals are emboldened, more people will carry guns, and the murder increase we have seen since August 2014 is only going to continue and likely deepen.”

If that caution does exist among some officers, Wexler, says, it likely won’t last because it’s not how police know how to do their jobs.

“There will never be enough police officers to adequately protect other police officers,” says @CWexlerPERF.

“There is national mood out there that makes everyone a little on edge,” Wexler said. “We are in uncharted territory. And in these kinds of situations and times, there is a tendency for police to be more reticent in engaging with the community. But what is important to recognize is that now more than ever the police need people in the community who have their back. There will never be enough police officers to adequately protect other police officers.”

Justin Smith, the Republican sheriff of Larimer County in Colorado, worries about the consequences of what backing off would mean for the middle/upper class community he serves.

He’s concerned that the recent violence by and against police officers will make it harder to retain good law enforcement professionals.

He says some of his deputies are expressing to him the emotional impact the recent violence has had on their families. Smith fears that disengaging would create more division and resentment toward a profession that demands connectivity.

“My biggest fear honestly with the things we are seeing and feeling is that this has the potential to turn local police against the community,” Smith told The Daily Signal in an interview. “To me, that’s the biggest threat out of this. If officers fall for that approach, we’ve lost the reason we are here. We are here to serve the community. If we fall into an us vs. them mentality, we have lost the game.”

‘What They Love’

Yamada, a 28-year veteran of the Montgomery County police, is proud of his 22-year-old son, Ryan, as he begins the second week of work in this same police force.

Father and son will be serving the community where they were both born and raised, an increasingly diverse county with more than 1 million people.

Though Ryan is coming up through the ranks in one of the most charged moments in policing history, Yamada is hopeful that his son’s experience will be similar to his own.

“I am proud he’s passionate enough to want to do something like this,” Yamada said. “It’s not the optimum time to say I want to choose a career in law enforcement. But when these kids are out here and decide this is what they want to do, you know now more than ever you will get a quality person. If they are doing it now, that’s what they love.”