In June of 2013, Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping met at Sunnylands, the former Annenberg estate in Rancho Mirage, Calif. The “shirtsleeve summit” was intended to promote informal discussions between the two leaders. It failed to meet even limited expectations. The Chinese leader even refused to stay at the estate.

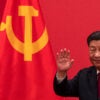

On Friday, President Xi Jinping will make a formal state visit to D.C., his first since becoming the head of the People’s Republic of China. Hopes for this meeting should be even more tempered than they were for the first, as relations between the United States and China have become even more contentious in the intervening years.

But if the two sides can manage a relatively honest discussion of their differences, the visit will be worth the time of both leaders.

One touchy subject that President Obama should raise is Beijing’s misbehavior in the South China Sea. China’s construction of islands there is a source of tension throughout the region. The U.S. has increased its surveillance of Beijing’s shenanigans, but Chinese State Councillor Yang Jiechi has pointedly observed that the U.S. is not a direct party to the territorial disputes and therefore should not get involved.

The two sides have fundamentally different views on South China Sea issues, including navigational rights through the area’s airspace and waters. (And, for good measure, similar issues in the East China Sea are highly disturbing to a key U.S. ally, Japan.) Given the wide divergence in perspective, Washington and Beijing are unlikely to reach agreement in this summit.

Cyber issues—a major irritant in bilateral relations—should get substantial attention, too. While the administration has not formally accused anyone of the massive Office of Personnel Management data breach, many Americans hold China responsible. The PRC government denies engaging in any hacking and notes that it is itself one of the most targeted nations.

Recent meetings between top Chinese and U.S. officials reportedly produced a consensus that “dialogue and cooperation on combating cybercrime serve the common interest of both countries and the international community.”

While those talks precluded the administration’s making good on its promise to retaliate against the hackers, they also raised the possibility that the summit will produce some kind of cyber security announcement. If so, the agreement will need to be substantive and enforceable.

Economic conditions—another source of contention—have changed markedly in both countries since the two leaders last met. China’s GDP, growing a robust 10% just four years ago, has slowed considerably over the last two years. Though pegged officially at 7%, actual current growth is more likely closer to 5% and slowing.

All three pillars of Chinese economic growth—exports, fixed asset investment, and the property market—are languishing. The current account surplus (a close proxy for the balance of trade) has shrunk from 10% of GDP in 2009 to just 2% last year.

Beijing will likely try to resuscitate exports growth by engineering a continued devaluation of the renminbi. But with the U.S. trade deficit with China expected to hit a record $350 billion this year, Obama will doubtless put pressure on Xi Jinping about currency manipulation. Maintaining unfettered access to the American market will be critical for China amid a slowing economy.

While America worries about devaluation of the renminbi, China worries about Washington’s inability to control its own spending and debt. Yet, at the end of the day, neither can dictate its respective economy’s behavior.

Moreover, both sides recognize the importance of the bilateral economic relationship. With some $590 billion in trade between the two economies, maintaining an amicable trading relationship is a win-win proposition.

Another shared concern and interest is the deteriorating situation in the Middle East. Now that the Islamic State has taken a Chinese man, Fan Jinghui, hostage, China finds itself among the ranks of nations whose citizens are being directly threatened by the terrorist organization.

The major powers clearly share a fundamental interest in maintaining the safety of their citizens in the face of growing terrorist threats. This common concern was demonstrated earlier this year when China’s Navy evacuated both Chinese and foreign nationals from Yemen.

Will the summit fundamentally change U.S.-China relations? Certainly not. But it’s an opportunity for two world leaders to speak frankly with each other, making clear their positions where they disagree and finding places where they can agree.

Building on the latter—especially in the areas of economics and counterterrorism—can lay the groundwork for complementing Xi Jinping’s dream of Chinese revival with a Chinese-American renewal.

Originally published in Investor’s Business Daily.