For many of the highest-profile U.S. Supreme Court cases, it all comes down to one man.

Though only 20 percent of cases each term are decided by one vote and 65 percent in the last term were unanimous decisions, litigants often craft arguments aimed at capturing his vote and pander to him at oral argument. Anthony Kennedy runs the court, according to conventional wisdom.

But is his time on top coming to an end?

Kennedy was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1987 after spending more than a decade on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit. A California native with ties to Reagan from his days as governor, Kennedy was the third choice to replace Justice Lewis Powell Jr. after the failed nominations of the late Robert Bork and Douglas Ginsburg. Known for his affinity for foreign cultures, Kennedy spends his summers teaching in Austria, travels annually to China with the American Bar Association and has advised nascent democracies on their constitutions.

On occasion—for good or ill—this affinity for foreign mores creeps into his work at the court. Chief Justice Roberts and others have described citing foreign law as “looking out over a crowd and picking out your friends” (meaning, it’s a way to find support for just about any legal argument).

But Kennedy approvingly cited European courts in his majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), striking down the state’s ban on sodomy, as well as in Boumediene v. Bush (2008), extending the writ of habeas corpus to detainees held at Guantanamo Bay. Likewise, he pointed to the “climate of international opinion” as not dispositive but instructive in limiting the availability of life-without-parole sentences for juvenile offenders in Graham v. Florida (2010).

Hailed “King Kennedy,” his ideology places him squarely in the middle of the two wings of the court. He often sides with the conservative justices in civil rights and campaign finance cases (e.g., Fisher v. University of Texas, Shelby County v. Holder, and Citizens United v. FEC), but he frequently casts the deciding vote in cases advancing socially liberal causes (Miller v. Alabama, United States v. Windsor, Romer v. Evans, and Obergefell v. Hodges).

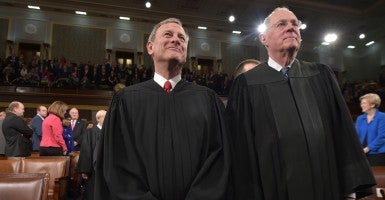

Last term, Kennedy was in the majority in all 10 of the cases decided by one vote. So far this term, Kennedy was been in the majority in 10 of 15 decisions. It may have been Kennedy’s court, at least for a time, but increasingly Roberts is gaining on Kennedy, leading some to suggest he is attempting to wrest control of the court away from his colleague.

Roberts is known as a judicial minimalist, favoring narrow decisions and large majorities. During his Senate confirmation, he likened the role of a judge to an umpire—it’s his job to “call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.”

Appointed to the Supreme Court by President George W. Bush in 2005, Roberts previously served as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. His career before joining the bench paints the picture of a poster child for the Federalist Society (full disclosure: I’m a member): law clerk to Chief Justice William Rehnquist, associate counsel in the White House counsel’s office during the Reagan administration and a stint in the solicitor general’s office.

But since he voted to uphold Obamacare in 2012, conservatives no longer consider Roberts a guaranteed vote in many cases. Since that decision, Roberts has broken with the conservative wing in a string of cases, such as McCullen v. Coakley (although a unanimous decision, Kennedy and the conservatives disagreed with Roberts’ reasoning), Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar, Yates v. United States, Young v. United Parcel Service, and North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission.

With the decision this week in King v. Burwell, Roberts further distanced himself from the conservatives—although Kennedy joined in the majority as well.

It’s fair to say Roberts acted less like an umpire and more like a player on Team Obamacare—willing to save the law at any cost. In his majority opinion, Roberts looked for ways to obscure the plain meaning of the statutory text to repair a law that simply wouldn’t work.

Dubious though his methods were, perhaps in Roberts’ mind he was limiting the damage (“jumping on the grenade”) of a potential decision written by one of the liberal justices. Maybe he fell prey to liberals’ admonitions that he safeguard the court’s reputation; or it might even have been an attempt to remove the temptation for people to resort to the court to settle purported political differences. Whatever his reason for deciding King v. Burwell, the chief justice is now in the running with Kennedy for the “swing vote.”

As the 2014-15 term wraps up, a clearer picture will emerge of this court and who’s truly in charge. One thing is certain: The world no longer revolves around Kennedy.