There’s no question the Internet has radically redefined the exchange of goods and services globally through reduced transaction costs and the increased transparency in markets. The success of online commerce has revolutionized shopping for billions of consumers.

Total annual online sales in the United States have increased tenfold since 2000 and grew at about 15 percent in 2014 alone. The effect of such a vibrant market is the creative disruption of existing business models, to the benefit of consumers.

>>> Read the Special Report: Saving Internet Freedom

The changes in commerce created by the online revolution frequently have been met with opposition by entrenched interests that profited from the old system and laws that long protected the status quo. We’ve seen much progress, but substantial reform still is needed in many areas.

Online Wine Shopping and Delivery

Internet-based sales of wine were long severely limited by the labyrinth of state and local laws limiting its shipment. These laws sheltered in-state distributors from competition by online sellers and were so restrictive that many vintners turned to modern-day bootlegging to sell their product.

The bans worked to hurt consumers: The Federal Trade Commission found the variety of wines available online was 15 percent greater than the local selection and was up to 20 percent cheaper.

Many of the bans have been overturned since 2003, thanks in large part to a Supreme Court decision that found bans on interstate wine shipments to be unconstitutional. But many problems remain. The direct shipment of wine remains prohibited (with some exceptions) in seven states, and almost all of the remaining states have some form of burdensome permitting requirement or fees associated with shipping wine.

Other regulations plague even the largest online distributors. Wine.com, the leading online retailer, had to spend $2 million and build seven separate warehouses just to comply with regulations in 2012.

Direct Automobile Sales

Although customizable products are widely available online (even for the most expensive items), there is one major life purchase that cannot be made online: a new car.

Given the ability to customize today’s autos, it should be easy to choose a make and model online, then buy it directly from the manufacturer. But such direct sales are now banned in all but a few states because of rules designed to protect local dealers from competition from out-of-state carmakers.

Again, these rules end up harming consumers. The dealership requirements block the 34 percent of American car buyers who said they would be likely to purchase a car online from doing so and add $2,000 to the cost of a new auto.

Even the government’s darling Tesla, a new entrant into the auto market, has struggled with statewide bans and other obstacles when the company tried to bypass dealers and sell directly to customers.

Allowing consumers to buy cars directly from manufacturers who sell online—rather than through a dealer who merely resells cars as a middleman—would give them greater access to customization, efficiency and choice.

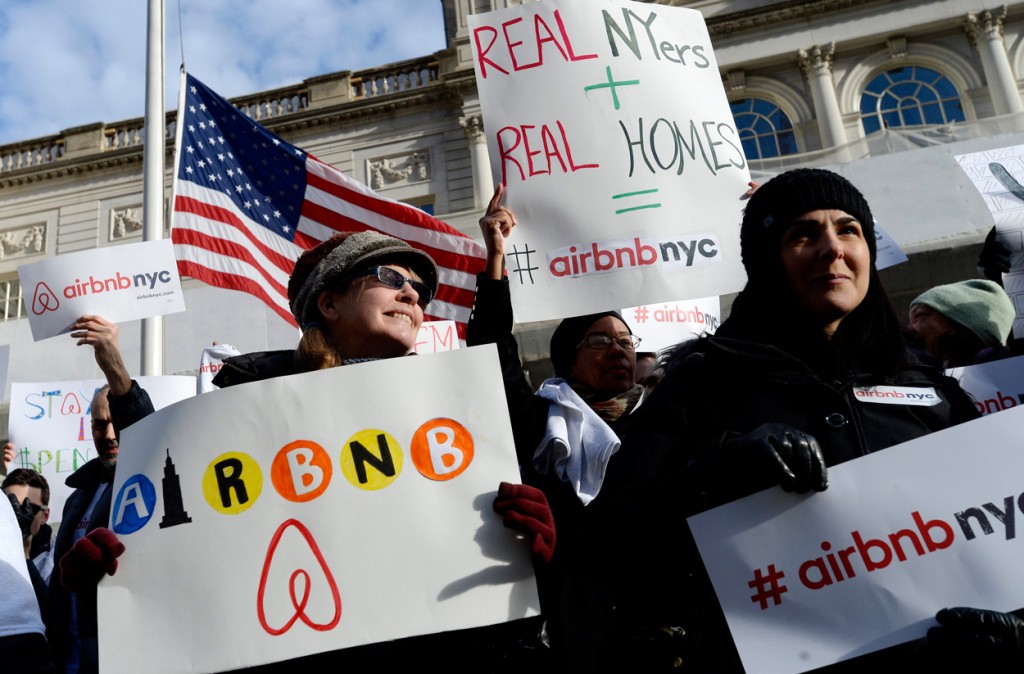

Supporters of Airbnb operations in New York City hold signs during a rally at City Hall before a hearing. (Photo: Justin Lane/EPA/Newscom)

The ‘Sharing Economy’

The rise of cheap mobile phones and data programs has allowed people to connect more easily than ever, enabling a more efficient exchange of goods and services.

Dubbed the “sharing economy,” online applications, such as ridesharing services (Lyft, Sidecar or Uber) or apartment sharing (Airbnb) have revolutionized industries by linking users directly to individuals who provide the requested service, such as a car ride, via the Internet.

These new “sharing” businesses, made possible by the Internet, do not fit neatly into any existing regulatory categories. Yet, the incumbent players have fought these new enterprises at every turn. Taxi cab monopolies in major cities attempted to ban ridesharing services outright or subject them to the same artificial restrictions and price regulation imposed on taxis. The hotel industry has fought to subject Airbnb to the full panoply of hotel rules.

Again, these rules often are imposed under the guise of consumer protection, but the regulations benefit entrenched firms, raise consumer prices and squash innovation. Rather than blindly applying existing rules to these new forms of commerce, policymakers should carefully reconsider whether those rules still make sense at all and specifically whether they make sense for new forms of business. The Internet has made these new forms of economic and consumer freedom possible; these benefits should not be dismissed because of fear of change.

Even though the Internet has flourished as a largely free market, myriad barriers remain. States should work to eliminate laws that inhibit the benefits of new business models and technologies to ensure the full potential of the Internet marketplace can be reached.