The new Congress isn’t getting Washington’s crazy spending under control. In fact, it’s just made it worse. By enacting the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (H.R. 2), lawmakers increased the nation’s deficits by $141 billion over the next ten years and guaranteed even larger debt beyond that. So much for their formal commitments and resolutions to secure a balanced budget in ten years!

As a fiscal matter, this bill is a disaster. First of all, it violates a long-standing precedent of paying for the doc fix. Since 2003, Congress has passed 17 short-term patches and paid for them 98 percent of the time. This bill provides a nine-year patch and offsets only a little more than a third of the cost.

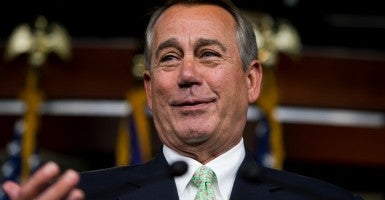

The bill also violates both the recently passed House and Senate budget resolutions, which assumed that the doc fix would be fully paid for over the next ten years. As the House and Senate Budget Committees head to conference to resolve their budgetary differences, the conferees face the inconvenient truth that the doc fix is not funded as previously assumed. Furthermore, this exercise is a reflection of how unserious Republican leadership is about the budget process when it’s inconvenient. Republicans in Congress can have disagreements about policy. But not adding to the debt should be one position they can unify behind.

As for the Medicare payment policy, the bill is a marginal improvement over a very bad Medicare status quo. For doctors, the bill creates greater predictability in Medicare payments. It will end the annual Chinese fire drill in which members of Congress flail about in a desperate, eleventh-hour attempt to stop their own stupid Medicare payment formula from imposing some draconian Medicare payment cut.

This exercise is a reflection of how unserious Republican leadership is about the budget process when it’s inconvenient.

As Scott Gottlieb, M.D., of the American Enterprise Institute notes, Congress has missed an enormous opportunity to make a major conceptual breakthrough in Medicare policy. It leaves most of the ugly bureaucratic paraphernalia of Medicare’s administrative payment system in place, and it does not reverse the growing government supervision over the practice of medicine.

How this new process will play out in practice is, of course, a genuine mystery. As John O’Shea, M.D., has warned, basing physician reimbursement on the quality and value of service rendered is going to be a mammoth practical challenge. Accurately measuring these things is far more problematic and demanding than President Obama and congressional leaders imagine, and well beyond facile and fashionable rhetoric about the need for “payment for quality over quantity.”

To offset a small portion of the bill’s costs, Congress authorized timid changes in Medigap policy (a slight limitation in first dollar coverage) and a means testing modification that is far less consequential than even President Obama’s budget proposal suggested. While adopting these tepid tweaks in the giant entitlement, lawmakers ignored robust Medicare proposals that have long attracted bipartisan support—even though these improvements would have yielded major savings, far more than enough to finance the SGR replacement bill.

The debate, nonetheless, showcased genuine Senate statesmanship. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, offered an amendment to spare Americans from the bill’s deficits, though his colleagues defeated the measure by a margin of fifty-eight to forty-two. Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., raised a budget point of order against the bill for its long-term deficit increases. It was a valid objection. Nonetheless, seventy-one senators voted against Sessions’ motion. That the bill passed both House and Senate with overwhelming majorities should not impress ordinary Americans. Huge majorities are hardly evidence of rational deliberation or hard-but-necessary choices made.

Indeed, Congress took the easy way out (more red ink) just to get the broken Medicare SGR problem “off the table.” But in accomplishing that short-term goal, they have imposed hundreds of billions in additional deficit spending. By 2035, according to the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, their pricey doc fix will have saddled taxpayers with more than $500 billion in new debt. Those financial burdens can’t be so easily moved “off the table” in taxpaying households across the country.

Originally published in The National Interest