Yesterday, California Gov. Jerry Brown met with water, agricultural, and environmental leaders to collaborate and discuss solutions to address the state’s worsening drought.

.@JerryBrownGov meets w/water, agricultural & environmental leaders from across CA to talk #CADrought. #SaveOurWater pic.twitter.com/KloExvGQtm

— Governor Newsom Press Office (@GovPressOffice) April 8, 2015

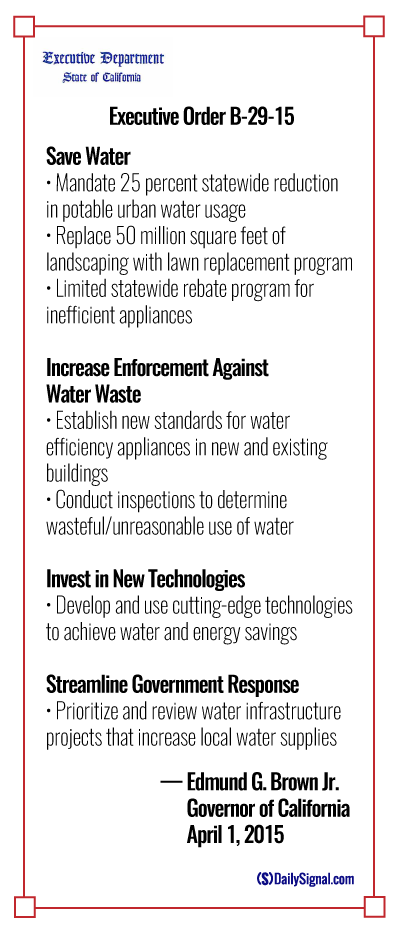

Brown came under criticism last week for an executive order that targeted urban water consumption, but mostly left alone agricultural usage.

The governor’s order mandates a 25 percent reduction in water use for urban areas—through February 2016—and also includes initiatives to encourage conservation.

Other than a requirement for agricultural water suppliers to submit sustainability plans, the executive order focused very little on the industry’s water consumption.

With a growing population of over 38 million, California is struggling to find a solution to its water crisis. But recent attention to water consumption has policymakers thinking of innovative ways to prevent future shortages.

Jennifer Clary, water program manager at Clean Water Action, sees the current crisis as an opportunity for California to make real policy reforms and encourage conservation.

“The silver lining of a drought is that it gives you a chance to change behavior,” Clary said. “Policies can do a little bit now, but a lot later.

“The silver lining of a drought is that it gives you a chance to change behavior,” Jennifer Clary, Clean Water Action

Clary says reforms like California’s groundwater legislation, signed by Brown last September, provides adequate oversight of groundwater pumping, including consumption by private parties and for public use.

According to the California Department of Water Resources, 30 to 46 percent of the state’s total water supply comes from groundwater.

The legislation provides local agencies with the power to “adopt and implement” a groundwater management plan for high and medium priority underground water basins.

However there are critics that say regulating consumption through government oversight and mandatory reductions is not the solution to California’s water problem.

Randy T. Simmons, professor of economics and finance at Utah State University, argues that California is missing a free market pricing system that could allocate water among consumers more efficiently.

“Ideally, water would be allocated based on a system of rights, so it could be traded in markets,” Simmons said. “Rather than letting water be allocated by price, California is trapped in a system allocated by the government.”

Simmons believes that raising the price of water in relation to consumption could signal to consumers the value of water as a natural resource.

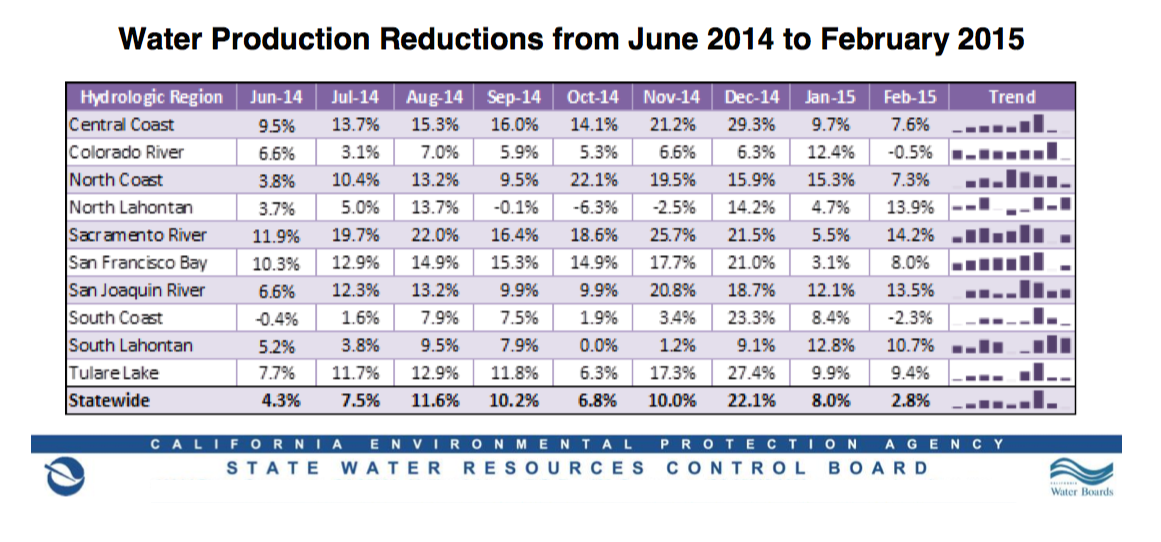

According to California’s Water Resources Control Board, urban water conservation in the month of February declined to 2.8 percent from 8 percent in January.

Despite the decline in conservation, the state has made a conscious effort through its #SaveOurWater campaign, to educate the public on simple ways to reduce consumption.

Water guzzlers would be punished under state proposal http://t.co/80QrQcyHhs via @SFGate #saveourwater #cadrought

— Save Our Water (@saveourwater) April 9, 2015

Nick Loris, energy research fellow at The Heritage Foundation, explained that the increase in consumption could be the result of inadequate pricing in relation to consumer usage.

“The absence of a proper water market with price signals that allocate resources appropriately will result in overuse and over consumption.” Nick Loris, The Heritage Foundation

“There are a lot of complex regulations and reforms that would need to happen,” Loris said. “But the absence of a proper water market with price signals that allocate resources appropriately will result in overuse and over consumption.”

David Zetland, assistant professor of economics at Leiden University in Amsterdam, has been studying water policy for over 10 years.

Zetland argues that the western United States, especially California, is slowly coming to the grips with its water management problem.

“After you run out of the abundance of water, you need to start looking at water through a different management paradigm,” Zetland said. “You have a physical system that is overextended, a political system that is very interventionist and a history in the world of not having water markets or water pricing.”

Despite political differences, Californian policymakers will be forced to decide how to best balance the water needs of communities, farms, and the environment.

“Breaking down the myth that your water comes out of a tap, and not from an ecosystem or a watershed, would be a great lesson to come out of this drought,” Clary said.

“Every time you make a choice to use that water, you make a choice to not use it somewhere else.”