Heritage analysts James Gattuso and Michael Sargent weighed in on the issue in a column last week:

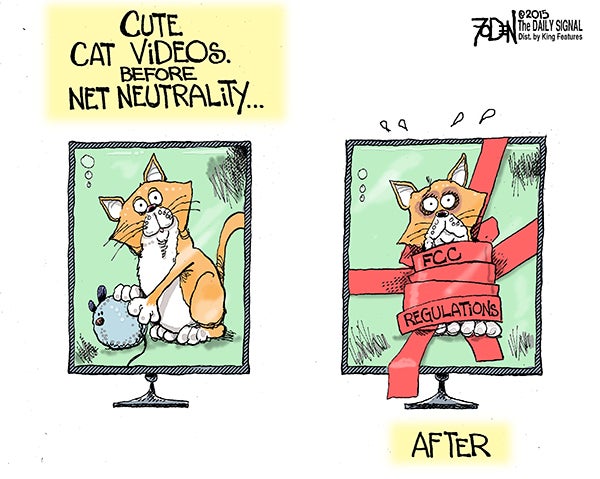

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted to place massive “net neutrality” restrictions on America’s Internet providers, in the process redefining them as public utilities.

If the decision stands, it would be a significant blow for the Internet and for its users. The issue is far from settled, however: the FCC’s rules will almost certainly be subject to review in the courts, where their fate is uncertain. Moreover, Congress—the constitutionally-charged body for lawmaking—may also have its say.

Under the new rules, wireless Internet service providers will also be treated as public utilities, facing thousands of regulations.

Network-neutrality regulation—roughly defined as government-imposed rules that force Internet service providers to treat every bit of content on their networks exactly the same way, limiting not just premium service offerings, but also discounts to consumers (such as T-Mobile’s plan to waive data fees for users of certain music services)—has been contentiously debated for over a decade now. Twice during this time, the FCC has tried to impose such rules—in 2005 and again in 2010—and twice it has been rebuffed by the courts, which found the agency lacked authority to act.

Hoping that the third time is the charm, the FCC, led by Chairman Tom Wheeler, proposed yet another set of rules last May. Initially, Wheeler intended to more or less re-adopt the 2010 rules, with minor changes intended to address the problems identified in court.

However, President Barack Obama upped the ante in November urging the FCC to turn Internet access providers into public utilities subject to comprehensive regulation of their activities with potential consequences far beyond net neutrality itself. Today, the three Democratic members of the FCC submitted to Obama’s urging and reclassified wireline Internet service as common carrier service, under Title II of the Communications Act, making them public utilities.

Under the new rules, wireless Internet service providers will also be treated as public utilities, facing thousands of regulations, despite the robust competition and unique technical constraints in wireless markets.

Devised for the static world of monopoly landline telephone service, public utility regulation will be devastating to today’s innovative and competitive Internet. Not only will the imposition of net neutrality rules themselves hurt consumers, but other restrictions triggered by public utility status—as well as billions in possible new taxes—will be similarly costly.

With the FCC’s vote, the battle over how (and whether) the Internet will be regulated by Washington moves to two new but familiar venues. The first is Congress, where members will want to—and arguably have a duty to—have a say. Congress’s options, however, are limited, given the likelihood of a White House veto of any bill that overturns the FCC. There are approaches worth exploring, however, such as attaching a reversal to other must-pass legislation such as an appropriations bill.

Opponents who want to keep the Internet dynamic and free of regulation may have a better chance of success in the courts. The unusually political nature of the decision, and the fact that it reverses previous FCC findings that Internet access is not a public utility, will raise serious questions as the propriety of the FCC’s action today. For wireless Internet service, there are additional hurdles for the FCC—including a specific provision in the Communications Act actually barring the agency from treating wireless data service as a public utility.

Today’s vote is clearly not the end of this long-running debate.