There was a time when the “China-lobby” meant supporters of The Republic of China (Taiwan). In the last couple decades, it has come to mean representatives of the American business community most eager to do business on the mainland, the People’s Republic of China, and willing to exercise influence in Washington in support of cordial relations.

Quite counterintuitively, it is these very advocates of controversy-free U.S.-China relations that the People’s Republic of China is now going after. A growing number of U.S. and foreign businesses say that they feel unwelcomed in China. A widespread brutal crackdown on corruption and “monopoly pricing” has unfairly been targeting foreign companies.

The alienation of these “friends of China” could have a major impact on broader U.S.-China relations.

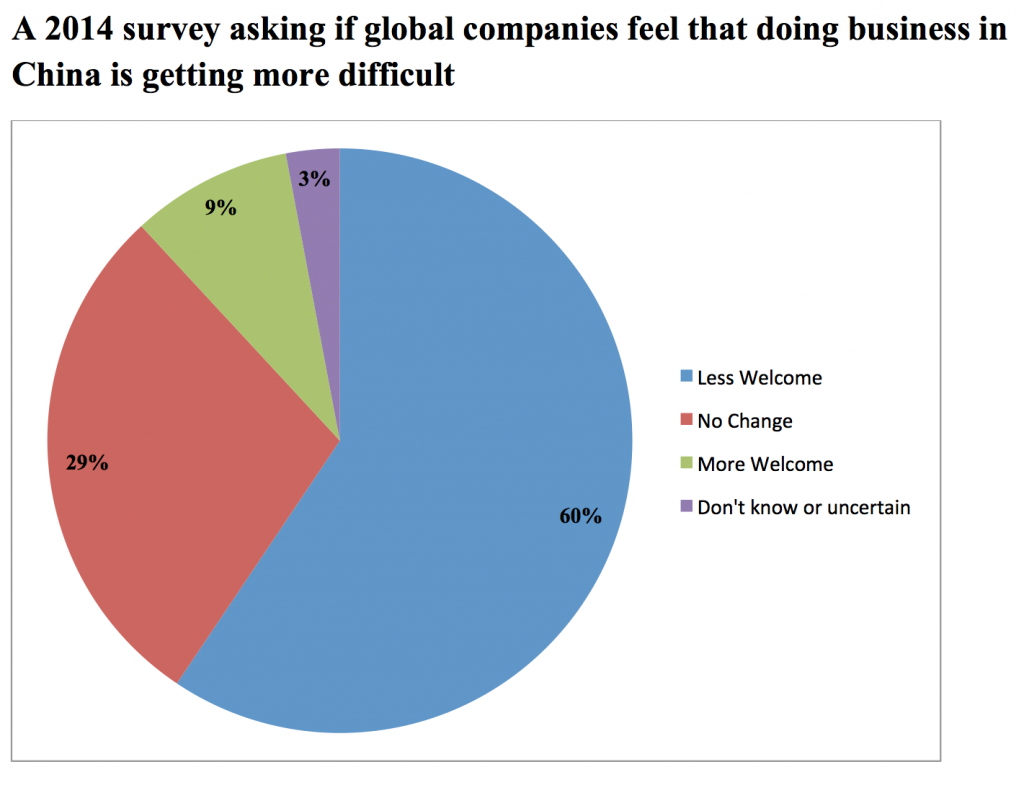

A 2014 survey by the American Chamber of Commerce revealed that 60 percent of its members now feel unwelcomed, an enormous leap from 41 percent in 2013. In a similar survey by the European Chamber, over 60 percent said that doing business in China was becoming more difficult.

Moreover, European companies stated that intimidation tactics were being used to force companies to pay heavy fines without any due process. According to the Wall Street Journal, high-profile firms targeted by Chinese regulators include Audi, Coca-Cola, Mercedes-Benz, Microsoft, Qualcomm, and Wal-Mart.

In 2014, Chinese officials found a dozen Japanese auto parts makers guilty of price fixing and slapped them with the highest antitrust fines in the country’s history, roughly $200 million. After a one-day trial held from public scrutiny, GlazoSmithKline was fined a staggering $489 million for bribery. If this was not enough, Beijing is increasing refusing business licenses and merger and acquisition activity to foreign firms and deporting the management.

According to the American Chamber, this shift in business treatment is rapidly shifting sentiment about China as a place to do business. As recently as seven years ago, China was the number one investment destination for a majority of its members. That figure has declined to 20 percent with many planning on scaling back expansion plans in the future.

Sources: WSL calculations of Chinese Commerce Ministry data; American of Chamber of Commerce (survey), The Wall Street Journal

The question is why has China embarked on this crackdown when direct investment has helped transform the economy over the past three and one-half decades? If China wants to continue moving up the technological ladder, it must import foreign know-how because it possesses little indigenous innovation.

The simplest explanation is that vested interests, like state-owned enterprises, provincial governments and government ministries are blocking the reformers determined to make the Middle Kingdom more market-oriented. Moreover, Xi Jinping, the president of the People’s Republic of China and general secretary of the Communist Party does not appear to be the liberally-oriented reformer he promised early in his term. In fact, he has declared open political season on anyone in China not appearing sufficiently Marxist.

There is likely to be another important long-term repercussion to this suppression. As American firms feel more threatened in China, the Chinese are likely to start losing their considerably powerful business lobby in Washington.