The Heritage Foundation’s Center for Data Analysis recently completed a preliminary macroeconomic analysis of House Ways and Means Committee chairman Dave Camp’s (R–MI) Tax Reform Act of 2014.

This draft proposal includes comprehensive tax reform to federal treatment on individual income, business income, and corporate income and is motivated by the proposition that “revenue-neutral” tax reform—reducing marginal tax rates on individual and business income and removing deductions on individual, business, and corporate income—would increase economic efficiency and lead to growth in the U.S. economy.

Our macroeconomic analysis starts from the assumption that individuals and businesses react to real-world changes in after-tax income and costs. Tax changes affect economic growth, largely through the way they impact the cost of productive factors in the economy.

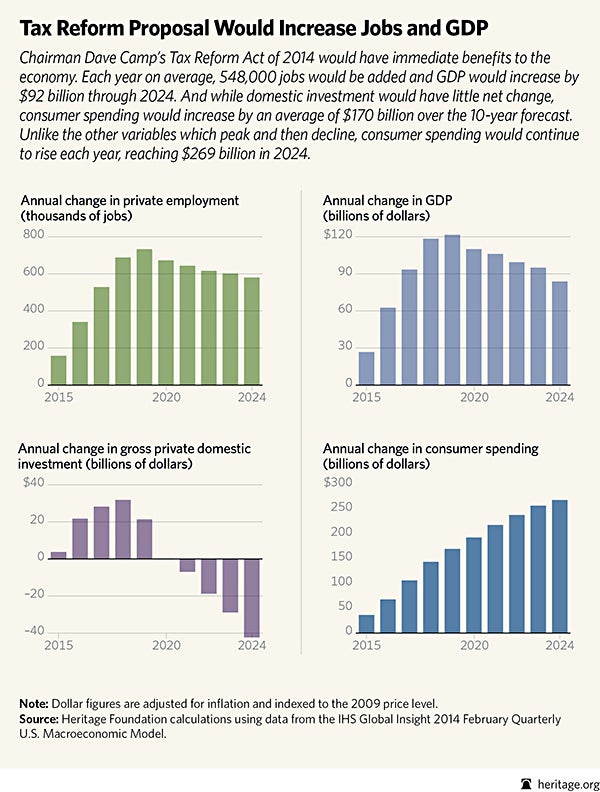

Overall, our macroeconomic analysis projects an average annual increase in real gross domestic product (GDP) of $92.3 billion over the 10-year forecast (2015–2024). The increase in real GDP growth peaks in 2019 at $121.6 billion and declines to a gain of $83.8 billion in 2024.

Total private employment increases by an average of 548,000 jobs per year over the 10-year period. The private employment gain also peaks in 2019 at an annual increase of 733,000 and then declines to an increase of 580,000 in 2024.

Gross private domestic investment increases very slightly, by $1 billion, over the average of the 10-year forecast. The path of business investment follows a similar path as GDP and employment but peaks one year earlier in 2018 at a gain of $31.8 billion. Unlike GDP and employment, the effects on private business investment turn negative beginning in 2021. By 2024, gross private domestic investment declines by $42.3 billion.

These estimates primarily reflect the impact to changes in the effective rates on corporate incomes and the changes to average marginal and average effective federal personal income tax rates.

On the individual income tax side, Camp’s proposal would replace the current seven statutory income tax brackets—ranging from 10 percent to 39.6 percent—with two primary tax brackets of 10 percent and 25 percent and a 10 percentage point surtax that effectively creates a 35 percent tax bracket. In addition, multiple phase-outs and limitations create additional effective tax rates and brackets.

The proposal would eliminate many significant “tax preference” items such as the personal exemption and state and local tax deduction. The elimination of such ineffective items has positive effects on tax efficiency, but some of these efficiencies are offset by an increase in the standard deduction to $11,000 for individuals and $22,000 for married couples and an increase in the child tax credit to $1,500.

On the corporate side, Camp’s proposal is highlighted by a reduction in the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent, elimination of accelerated depreciation, amortization of the research and development tax credit, changes in the treatment of foreign source income, a new bank tax, and elimination of many “tax preference” items.

The 10 percentage point reduction in the top corporate tax rate and treatment of foreign source income produce significant favorable economic impacts, but these positive effects are dampened, particularly in the second half of the 10-year window, by an increase in the cost of capital and investment for many corporations.

While this is a laudable attempt to get the ball rolling on overhauling the federal tax code, there are areas where tax reform could move forward in a better, more conservative fashion. We’ve outlined a few steps here.

One Reply to “Heritage’s Macroeconomic Estimate of Camp’s Tax Reform Proposal”