Yesterday, the Brookings Institution released updated statistics on the role of health care jobs in the broader economy. The study’s findings provide interesting grist for the ongoing debate about Obamacare’s impact on jobs. Three theories follow from the data.

1. Obamacare Has Not Affected Health Care Jobs

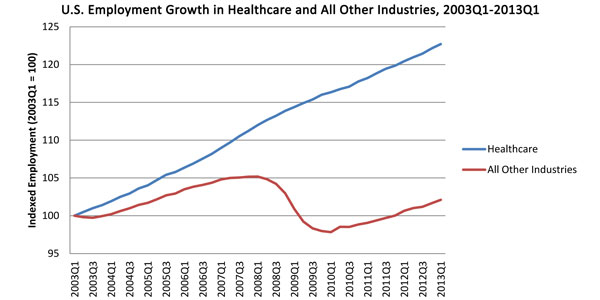

The chart showing a steady-state rise in health care employment over the past decade illustrates this point perfectly. As costs continue to rise, and our society continues to age with the impending retirement of the baby boomers, health care employment has steadily grown.

But the fact that health care hiring has increased at virtually the same pace since 2003 demonstrates the law’s minimal to nonexistent effect on employment trends that preceded its enactment.

2. Obamacare: Little Effect on Health Care Jobs, Little Effect on Health Care Costs

Labor costs comprise one of the major components of health care spending. A report from the American Hospital Association last year found that labor costs were the largest single driver of health cost growth, accounting for more than one-third of the overall rise in hospital prices—a percentage that has remained fairly constant over time.

It’s therefore difficult to assert that Obamacare has permanently “bent the curve” on health costs if the largest driver of health costs—the labor force—has grown unabated. Rather, it seems more likely that the recent slowdown in costs stems largely from the recession and struggling families forgoing health expenses, as a recent Kaiser Family Foundation study concluded.

3. Not Reducing Health Costs = Reducing Non-Health Jobs

Nancy Pelosi’s infamous claim at the White House health summit that Obamacare would “create 4 million jobs–400,000 jobs almost immediately” wasn’t based on the health sector creating more jobs—in many respects, it was based on the sector creating fewer new positions.

A 2010 Center for American Progress report, the basis for Pelosi’s claim, asserted that Obamacare would create more jobs outside the health sector by slowing the growth of costs within the sector—essentially, a rebalancing of costs and jobs away from health care and toward other industries.

Of course, as other analysts have noted, the converse is also true: If health care jobs continue to grow—as they have since Obamacare’s enactment—those growing health costs will hinder the competitiveness of non-health industries, to say nothing of our massive entitlement deficits.

It’s why anyone who wants to preserve American economic preeminence should want health care growth to slow, even if it means that some new health care jobs aren’t created. It’s also why analysts should be worried that Obamacare hasn’t fixed that problem in the slightest.