Martin Luther King is rightly remembered for his dream, first articulated on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial 48 years ago this Sunday, that the principles embodied in “the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence” would one day be vindicated and applied to all men, regardless of “the color of their skin.” Fewer remember that in the ensuing years before his untimely death in 1968, King gradually abandoned the dream of equal rights and sought instead “the realization of equality” through government redistribution of wealth.

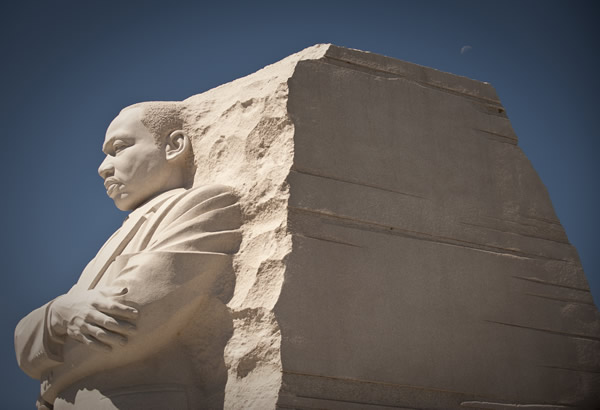

How fitting, then, that the new Martin Luther King Memorial, unveiled Monday on the National Mall in Washington, DC, should stand between the Lincoln and FDR memorials—the former a tribute to the greatest champion of the Founders’ vision of equality, the latter a monument to the President who redefined rights and expanded the reach of government like no one else.

The location of the MLK Memorial testifies to the two incompatible conceptions of equality and rights that King, at different times, defended. In commemorating his legacy however, King’s earlier words and accomplishments should take precedence.

From 1955, when he led a successful bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, to the Selma campaign that led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, without forgetting the March on Washington and the Birmingham campaign which culminated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, King worked indefatigably to secure the civil and political rights of black Americans.

To fulfill his dream of integration, King also advocated an ethic of self-reliance and hard work, anchored in stable family structures. And for those on the secular Left who are quick to appropriate MLK, the obvious should be stated: the Reverend King drew strength from his faith and inspiration from the words of Scripture.

King’s true legacy lies in his struggle for civil rights and in his defense of the American ideal of self-improvement through work. This is why we speak of “Martin Luther King’s Conservative Legacy,” of “The Conservative Virtues of Dr. Martin Luther King” and of “King’s Conservative Mind.”

We do so, however, while acknowledging that from 1965 onward—in the last three years of his life—King increasingly turned his attention away from civil rights issues to fighting poverty and protesting the Vietnam War. In doing so, the exhortations to work hard gave way to calls for government intervention. As he wrote in his 1967 book Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos Or Community?: “the ultimate way to diminish our problems of crime, family disorganization, illegitimacy and so forth will have to be found through a government program to help the frustrated Negro male find his true masculinity by placing him on his own two economic feet.”

In focusing on the pre-1965 Martin Luther King, we do not conveniently cherry-pick those aspects of King’s thoughts that we prefer. Rather, we honor his great and distinctive contributions to American history. And these contributions owe more to Lincoln than to FDR.

14 Replies to “MLK Memorial: Remembering the Dream or Rehashing the New Deal?”