It Takes 4 Times Longer to Become a Hair Braider Than an EMT in Oklahoma

Melissa Quinn /

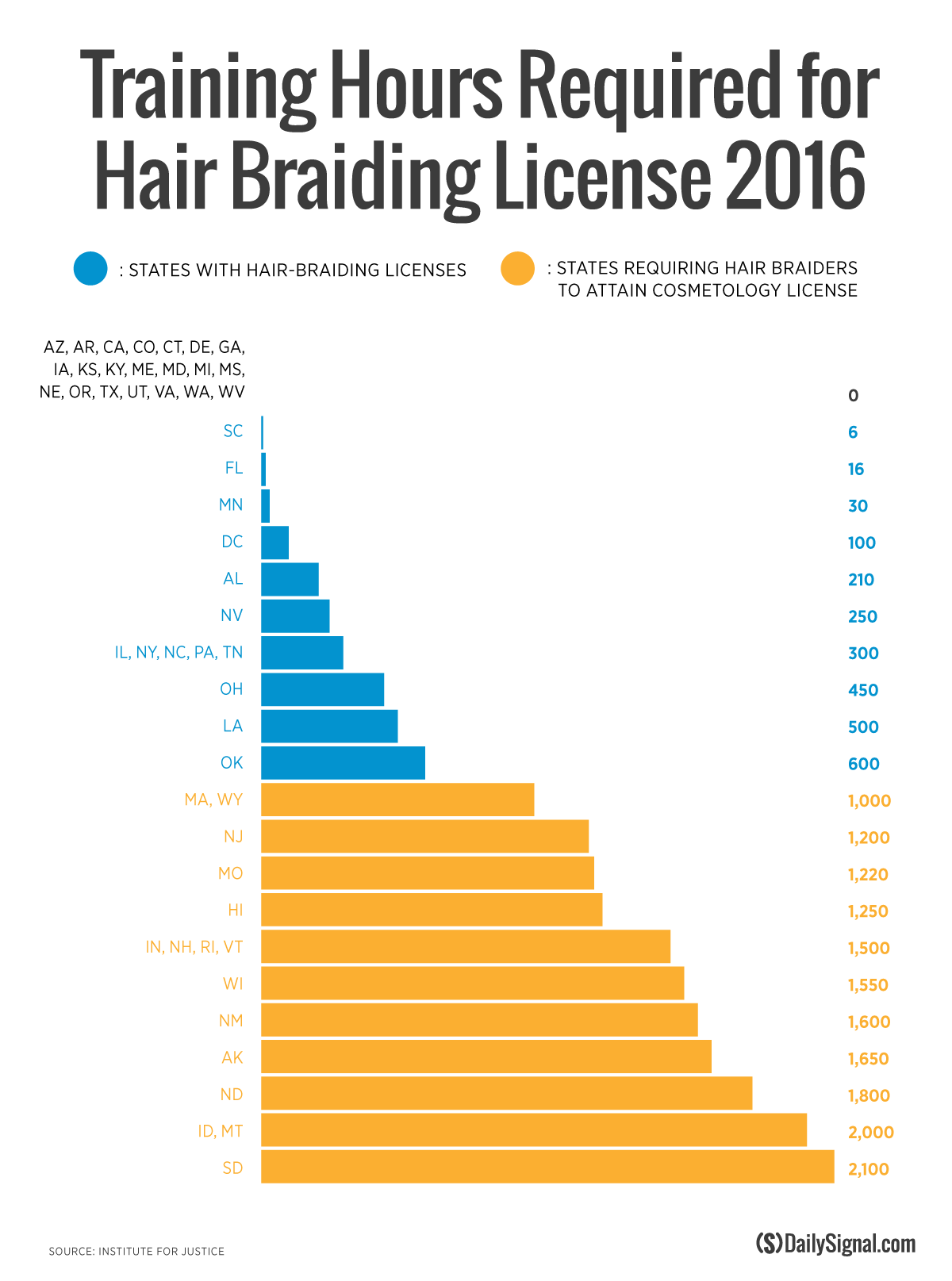

For aspiring hair braiders in more than half of the United States, obtaining the license needed to work this job can take as few as six hours and as many as 2,100 hours, or about 262 eight-hour days.

But in 10 places that require hair braiders to get approval from local and state governments, a new report from the Institute for Justice found that occupational licensing requirements have little impact on public health and safety. Instead, they deter hair braiders from entering the profession.

“We need public safety. We need consumer quality. But we also just have to have systems that make sense and let people innovate and let people trying to make it in our society be successful and not have to depend on the government,” Mark Holden, general counsel for Koch Industries and an opponent of occupational licensing, told The Daily Signal.

“Occupational licensing on it’s face, it’s one of those things that makes sense, right? We want to make sure people know what they’re doing,” he continued. “But when you unpack it a little bit and dig down beyond the buzzwords, you see a lot of time it’s really just a rigged system where it’s rent-seeking by those in power to get an unfair advantage over others.”

Occupational licensing refers to the state and local rules that require a job-seeker to get approval from a government-sponsored board before he or she can start working in an occupation.

Many agree that those working in professions dealing directly with public health and safety—doctors, lawyers, and pilots, for example—should need a license to work.

But policymakers have seen an uptick in the number of jobs that now require licenses—jobs like hair braiders, florists, makeup artists, and barbers.

“These occupations are a great first step for people really in a lot of places where there may not be a lot of opportunity to have hope, to start to build a business, and from there great things can sprout,” Holden said. “And government in a lot of ways, good intentions or not good intentions, it doesn’t matter, stifles it and prevents it through these laws and rules that don’t enhance public safety, that don’t make consumer quality better, and hurt the people who are forced to endure that harm.”

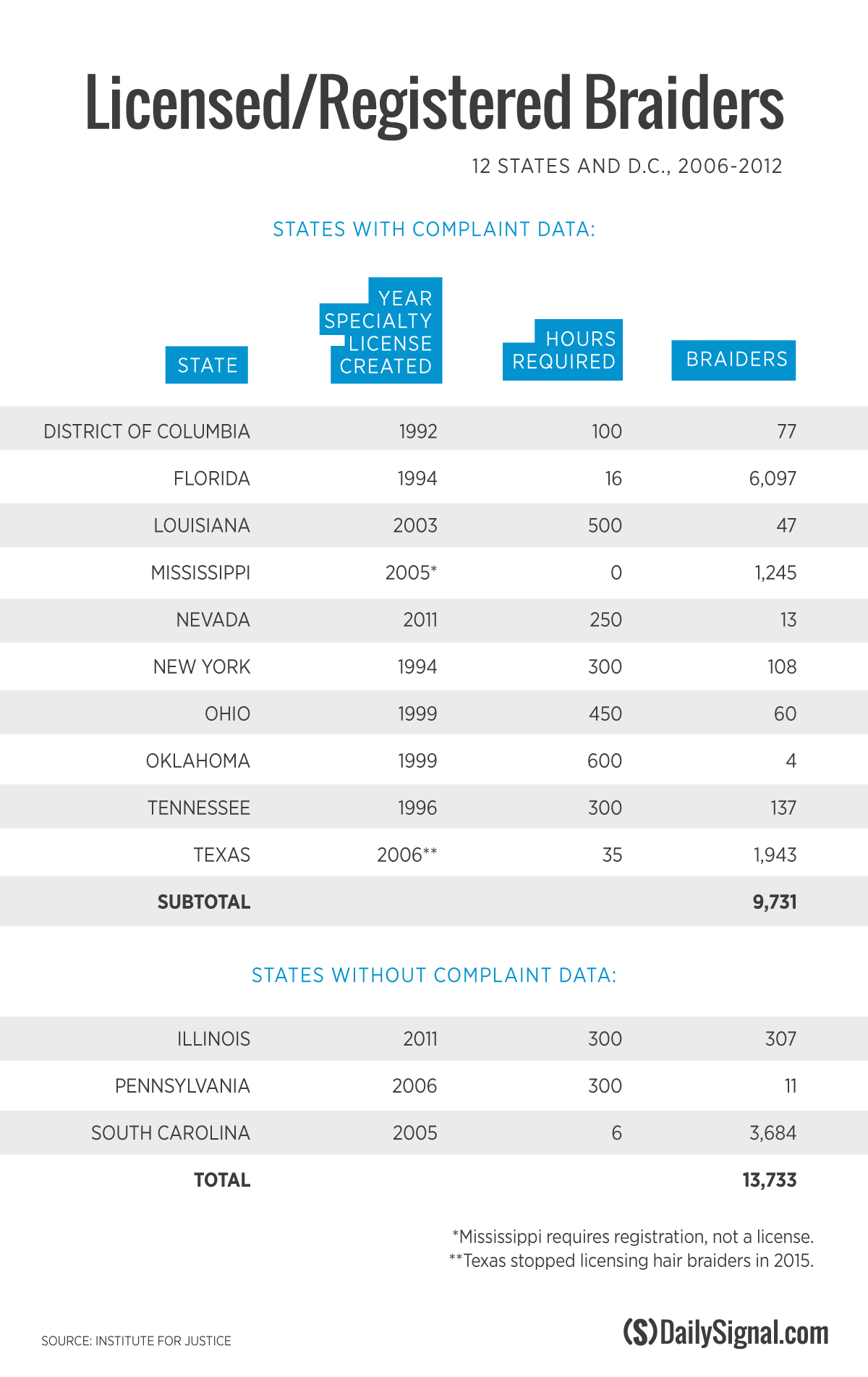

The Institute for Justice compiled complaint data between 2006 and 2012 for hair braiders from nine states—Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas—and the District of Columbia to further determine the impact licensing laws have on this profession.

In 14 states, aspiring hair braiders are required to attain a license specifically for braiding, and in those states, the number of hours in required training ranges from a low of six in South Carolina to a high of 600 in Oklahoma—nearly four times as many hours as it takes to become an emergency medical technician in the state, according to the Institute for Justice.

Sixteen states, meanwhile, require aspiring hair braiders to attain a cosmetology license, which are often more costly and require a minimum of 1,000 hours of training or education, required in Massachusetts and Wyoming, for example.

South Dakota requires the highest number of training hours, 2,100, for hair braiders to become licensed cosmetologists and practice their craft.

By comparison, a massage therapist working in South Dakota is required to complete just 500 hours of training, according to the state Board of Massage Therapy.

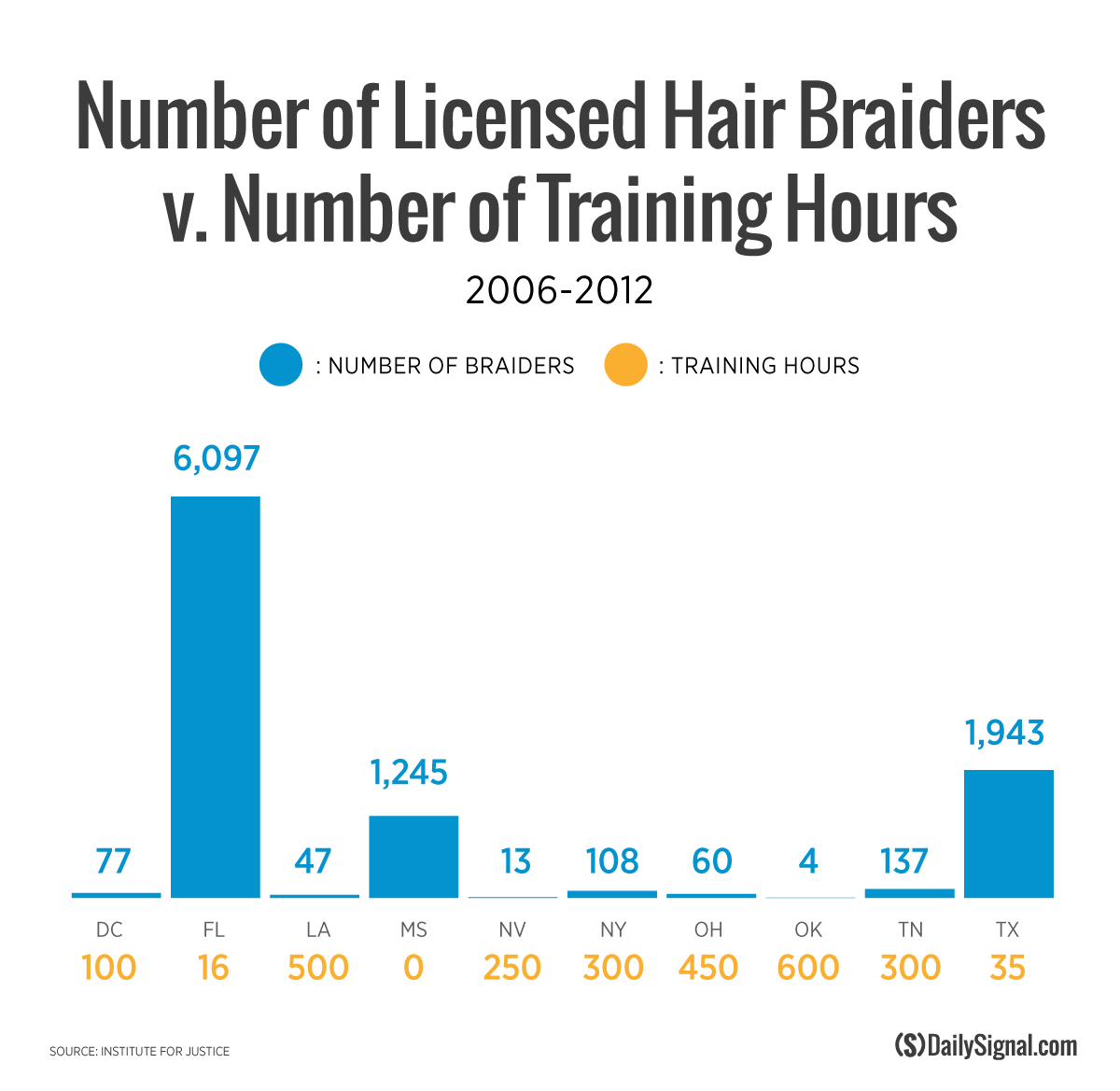

According to the report issued by the organization, states with higher numbers of training hours have less licensed hair braiders compared to those with fewer required training hours.

Louisiana, for example, requires aspiring hair braiders to complete 500 hours of training and had just 47 licensed hair braiders from 2006 to 2012, according to data obtained by the Institute for Justice.

Neighboring Mississippi, by contrast, doesn’t require any hours for training for hair braiders, but does require them—more than 1,200 in 2012—to register with the state.

“The best way to think about occupational licensing is its scope,” Angela Erickson, the senior research analyst with the Institute for Justice who authored the report, told The Daily Signal. “It’s not just affecting someone who’s a hair braider.”

A study conducted by the White House Council of Economic Advisers last year found that the percentage of the U.S. workforce needing a license has increased exponentially in nearly six decades.

In the 1950s, just 1 in 20 workers living in the United States needed a license to work. By 2008, that number rose to 1 in 4, according to the White House.

“[Occupational licensing] is affecting your neighbors. It’s affecting your families. It’s affecting people doing somewhat lower-income jobs such as cosmetologists and barbers, people who are contractors, people who paint your home,” Erickson said. “It’s affecting a larger amount of people over time, and it’s continuing to grow.”

A Trickle-Down Effect

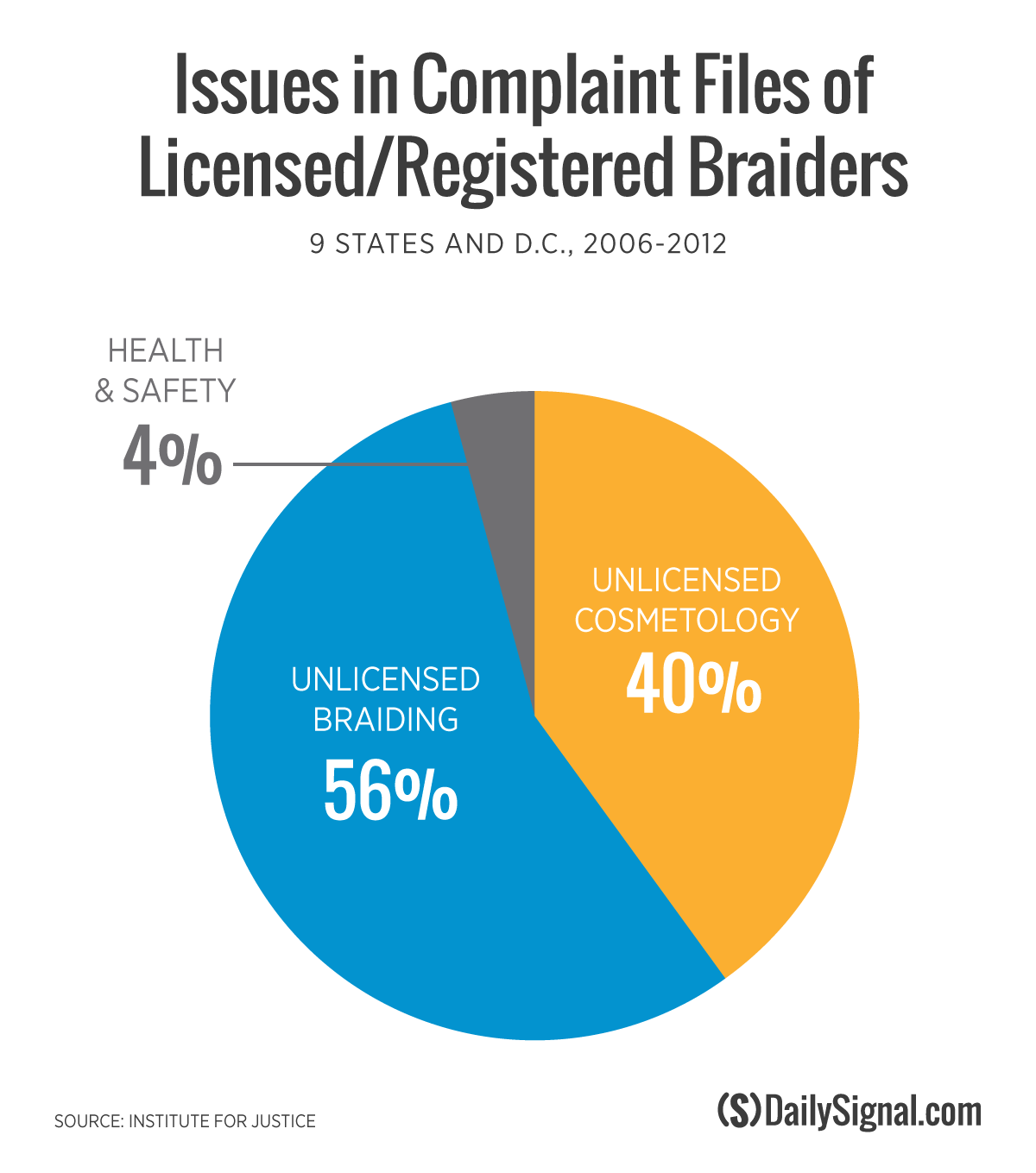

State boards and commissions are charged with regulating hair braiders, and many of those boards argue licensing is necessary to ensure public health and safety. However, when the Institute for Justice looked at complaints filed in nine states and the District of Columbia, the organization found few complaints were filed against hair braiders.

According to the Institute for Justice, 103 complaints were filed from 2006 and 2012 against more than 9,700 licensed or registered hair braiders in the nine states and the District of Columbia the group examined data for.

Of those 103 complaints filed, the vast majority were related to unlicensed activity—56 percent of issues cited in complaints were tied to unlicensed braiding and another 40 percent of those issues cited were tied to unlicensed cosmetology.

Additionally, the majority of complaints were filed by cosmetology boards.

Of the 103 complaints filed, one was filed by a customer, 77 were filed by cosmetology boards, and 24 were filed by other licensees or competitors.

The small number of complaints from customers, Holden said, shows that the idea that licensing is needed in these professions to ensure public health and safety is often a false narrative pushed by the government.

“It starts out with good intentions, doctors, dentists, lawyers, then electricians, plumbers, and it all just trickles down,” Holden said. “Human nature is we’ll say it’s safety, but it’s protecting [those in power]. The government is picking winners and losers, and it ends up hurting people more and hurting quality.”

Gaining Momentum

Occupational licensing has drawn the attention of not only Holden and the network run by Charles and David Koch, but also that of the White House.

“It’s an issue that’s something all Americans—left, right, Republican, Democrat, independent—can agree on and should be caring about,” Holden said. “It’s an issue that impacts all the states, all the individuals, and it’s really one of these things we see that’s just basically a huge barrier to opportunity for a lot of people who want to be entrepreneurial and be successful in this country.”

In January, Holden and Valerie Jarrett, a top adviser to President Barack Obama, met at the White House to discuss efforts to roll back licensing requirements.

White House press secretary Josh Earnest told The Daily Signal’s Fred Lucas earlier this month that Obama and his administration are committed to addressing occupational licensing, particularly as it relates to service members and their families who are disproportionately affected by licensing requirements.

“There are a number of executive actions that this administration has taken to try to streamline occupational licensing in a way that would make the economy more efficient,” Earnest told The Daily Signal, continuing:

…The transfer of [service members’] skills to the private sector has been impeded by overly burdensome regulations, and streamlining that process and facilitating the ability of our veterans to work in the private sector and use those skills in the private sector is something the administration has been quite focused on, both because it could improve the economic opportunity for veterans, but also could strengthen our economy.

Additionally, Sens. Ben Sasse, R-Neb., and Mike Lee, R-Utah, introduced legislation earlier this month tackling occupational licensing requirements in the District of Columbia and on military bases, where Congress has jurisdiction.

But the true momentum behind occupational licensing, specifically for hair braiders, comes from statehouses, Erickson said.

Since 2004, 15 states eliminated licensing for hair braiders, with 13 involving legislative reforms.

But the bulk of state legislatures took action within the last two years.

In 2015 and 2016, nine state legislatures—in Arkansas, Colorado, Maine, Texas, Delaware, Iowa, Kentucky, Nebraska, and West Virginia—eliminated licenses for hair braiders.

Erickson said the action at the state level can be attributed not only to heightened public awareness, but also grassroots efforts from hair braiders across the country protesting licenses schemes.

“[Occupational licensing] is affecting low-income minorities and immigrants,” Erickson said. “It’s affecting these communities who are trying to get their legs on the first couple of rungs of the economic ladder.”