Tammy Nutall-Pritchard had been braiding hair with her older sister, Debra Nutall, since she was 18 years old.

Nutall taught Nutall-Pritchard the craft when she was 15, and the sisters would stand side-by-side behind the chairs of scores of clients at Nutall’s Memphis, Tenn., salon who came in to get their hair braided while chatting and gossiping with customers.

Nutall-Pritchard did well—she charged around $300 per head and sometimes made more than $1,000 each week.

“It gave me joy,” Nutall-Pritchard, 47, told The Daily Signal of working with her sister. “She told me, ‘You learn a skill, it will bring an income for you if you do it the right way.’ She taught me to be the woman I am today, and she taught me that you can be your own boss.”

But Tennessee’s onerous licensing laws governing natural hair stylists like Nutall and Nutall-Pritchard eventually drove Nutall out of the state she and her family have called home their whole lives.

As a result, Nutall-Pritchard, who worked at the shop for more than six years, was out of a job.

Now, the 47-year-old works as a school resource officer to support her three sons.

In the meantime, Nutall-Pritchard wants to continue working in friends’ salons, shampooing hair and socializing, while making some extra money on the side.

But in Tennessee, Nutall-Pritchard needs a license to do that, too.

“Something so simple, they make it so hard,” she said of the state. “Something as simple as shampooing, they make it so hard for a woman like me to make money for a better life.”

So Nutall-Pritchard, with help from Nutall and Leanna Malone, Nutall’s granddaughter, teamed up with the Beacon Center of Tennessee, a free-market think tank, to challenge the state’s shampooing licensing laws and is arguing those regulations violate her economic liberty.

“For a common, everyday job like shampooing, we’re not talking an engineer or a doctor or something like that,” Braden Boucek, the Beacon Center’s director of litigation, told The Daily Signal. “For a common, everyday calling like shampooing, you have a fundamental right, and the state can’t just arbitrarily burden it.”

“To earn a living is a right,” he continued. “Everybody deserves a good job, and that’s something we should all be able to agree on.”

An Ongoing Licensing War

Nutall-Pritchard and Nutall have a long history of fighting licensing laws in Tennessee, but for them, the enduring battle scars come from regulations tied to natural hair styling.

Nutall learned braiding when she was a child and views it as an art form. At the time, there were no hair braiding salons and, as far as she knew, no easy way of opening one. So instead, Nutall decided to braid hair in between her 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. shift as a nurse’s assistant.

Nutall’s braiding was unique, and Memphis women began recognizing her styles in the supermarket or at the gas station. Nutall’s client base grew.

Nutall decided to purchase a space in an old bank building on Lamar Avenue in Memphis to compensate for her growing business. There, in 1995, she opened Dee-Nu-Tall Braid Academy.

Nutall continued to see success. After living on welfare and in public housing, the mother left the welfare rolls and bought a new house. The year she opened her salon, Nutall purchased her first brand new car: a 1995 Toyota Camry.

“I had to do something to come out of public housing, and it was honest and fair,” Nutall said of her business. “It bought me a new home and a new car and got me off of welfare and out of public housing, and therefore my children had an opportunity to see life in a different way.”

In 1996, the Tennessee General Assembly passed a law requiring natural hair stylists to attain a cosmetologist’s license through the state’s Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners.

Natural hair braiders like Nutall had excelled in their craft for years, learning braiding from their mothers and grandmothers. But now, the state was telling them they had to log more than 1,500 hours of education through an eight-week course with costs topping $12,000, Nutall recalled, and all for a skill she pioneered in Tennessee.

The business owner lobbied state and federal lawmakers in both Nashville and Washington, D.C., urging them to roll back the regulation. Nutall tried to explain that a cosmetology license, which covers perming, relaxing, and dying, was unnecessary for natural hair stylists, particularly because their craft dissuades the use of chemicals used by cosmetologists.

“I wanted us to stand as a separate entity from cosmetology because we didn’t do anything with chemicals,” Nutall said. “We can twist hair with our hands or braid with our hands. You don’t even need combs necessarily.”

The state board didn’t budge, and Nutall ended up closing her salon in 2010 because of the expensive licensing requirements.

Instead, Nutall moved 13 miles south of Memphis, across the state line, and into Southaven, Miss. In the Magnolia State, another braider, Melony Armstrong, had successfully challenged the state’s licensing regulations for natural hair stylists, just as Nutall had attempted to do in Tennessee.

Because of Armstrong’s efforts, hair braiders in Mississippi pay $25 to register with the state and no longer have to log 1,500 hours of education and experience to earn a cosmetology license.

“When I had my own business, being restricted like that, it really takes away from your business,” Nutall said of Tennessee’s licensing laws. “It can cause you to fail as a business owner because you need to have as much activity of work going as possibly when you own a tight business. You don’t want to be the only one in there. You also want to make revenue and an avenue for other people to earn an income.”

‘The Door Is Barred’

In Tennessee, not only do natural hair braiders need to attain a license, but those shampooing hair in their shops—known officially as shampoo technicians—do, too.

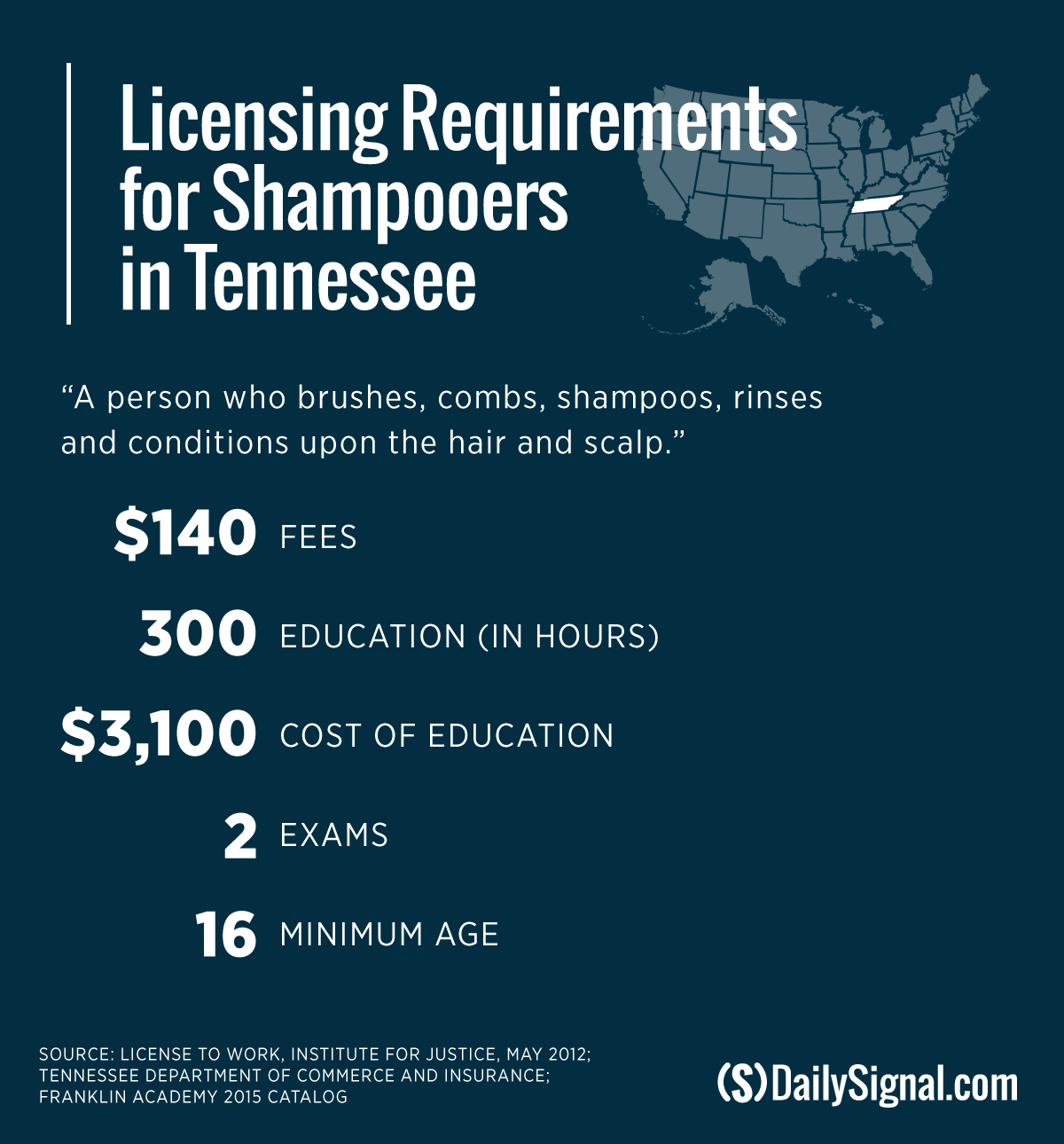

The Tennessee Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners defines a shampoo technician as a “person who brushes, combs, shampoos, rinses and conditions upon the hair and scalp,” and the state began requiring shampoo technicians to attain a license in 1996.

To get a license, aspiring technicians must pay a $140 fee to the state, complete at least 300 hours of education in a course on the “practice and theory” of shampooing, and must be at least 16 years old.

A 2015 catalog of coursework from the Franklin Academy lists tuition for the shampoo tech program at $2,700, which doesn’t include the $400 required book and kit, or the $100 in application and registration fees. The Franklin Academy is a nonprofit institution based in Cleveland, Tenn., that trains those seeking licenses in cosmetology.

“The curriculum is burdensome, expensive, and totally irrelevant to what they want to do,” Boucek said. “The fact they’ll specify what kit you must buy and that you have to go to school shows they’re concerned about making the individuals spend money that benefits the schools and limits competition, which is what you would expect from a statutory regime that is designed to benefit existing market participants.”

Though the state outlines the requirements to attain a license to work as a shampoo technician, it’s difficult to find a school offering a program solely in that field. The Franklin Academy, for example, no longer lists “shampoo technician” among its programs of study in its 2016 catalog of courses.

Kevin Walters, communications director for the Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance, told The Daily Signal in an email that none of the licensed schools offer a program specifically for shampoo technicians. However, Walters said a student interested in attaining a shampoo technician license can ask a school to provide that program, and they will do so.

Boucek, though, pointed out that those looking to acquire a license to work as a shampoo technician are effectively forced to work toward a cosmetologist license, which requires more coursework and training.

“Either they’re doing it illegally, or licensed cosmetologists are doing it,” Boucek said of shampoo technicians. “That’s a full on career. You have to go to school for years. That’s singeing, cutting hair, straightening—all these things the shampooers don’t want to do.”

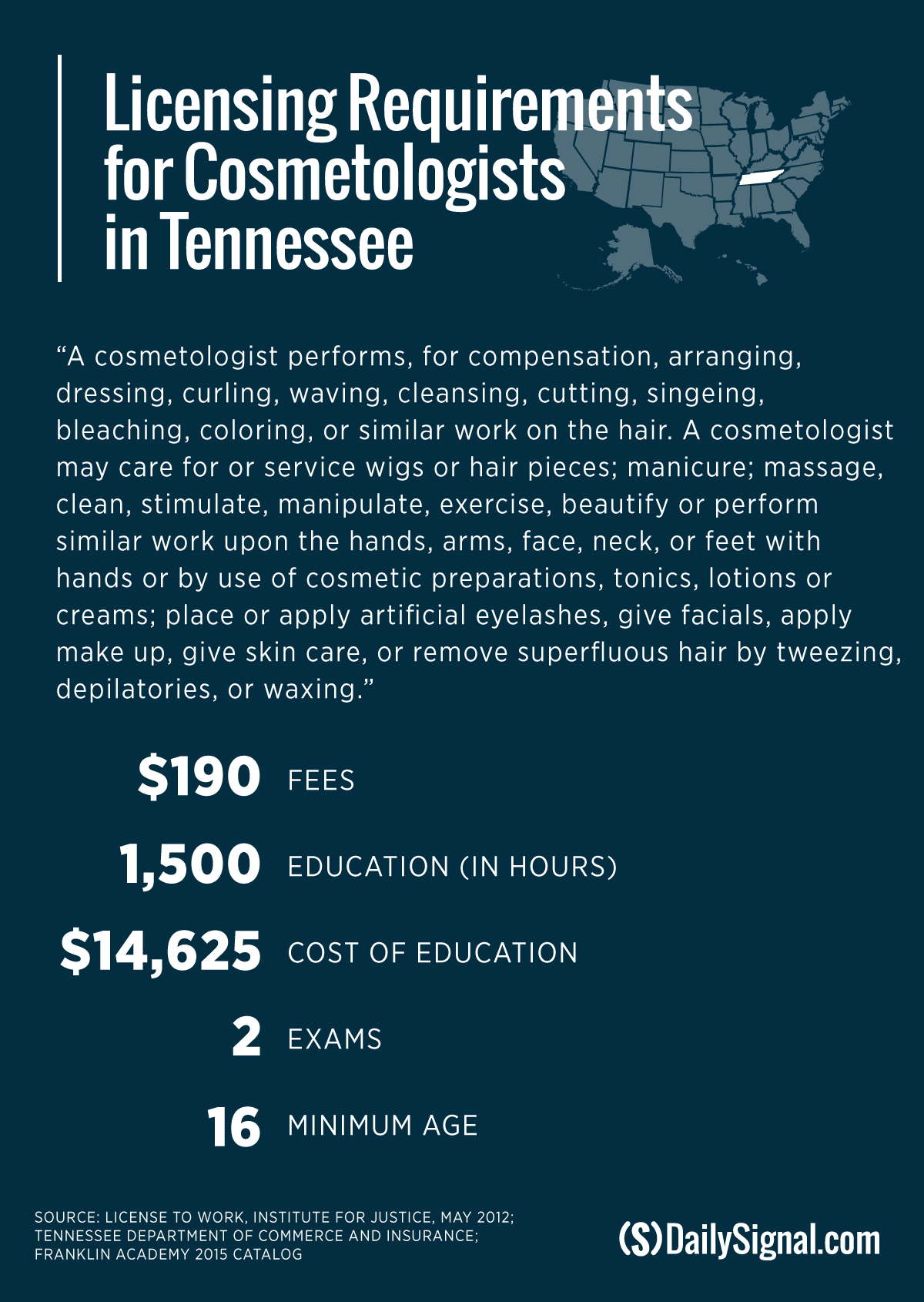

In Tennessee, attaining a cosmetologist license requires more money and more time than that of a shampoo technician. Aspiring cosmetologists must pay a $190 fee to the state, complete at least 1,500 hours in education, pass a class, take two exams, and be at least 16 years old.

At the Franklin Academy, the cosmetology program cost $13,500, and that didn’t include $1,125 for books and a kit.

“In this case, [the cosmetology board] structured it so you’re required to go to school to get the shampooing license, and it’s impossible to go to school to get the license,” Boucek said. “It’s the definition of a monopoly. Only market participants can do it, and the door is currently barred altogether.”

As of April 28, there were 36 licensed shampoo technicians and more than 32,816 licensed cosmetologists in Tennessee, Walters said. Another 5,656 cosmetologists had expired licenses but were in a grace period for renewal.

The Occupational Licensing Creep

Tennessee’s licensing regulations for shampoo techniques represent a small fraction of the laws governing the U.S. workforce.

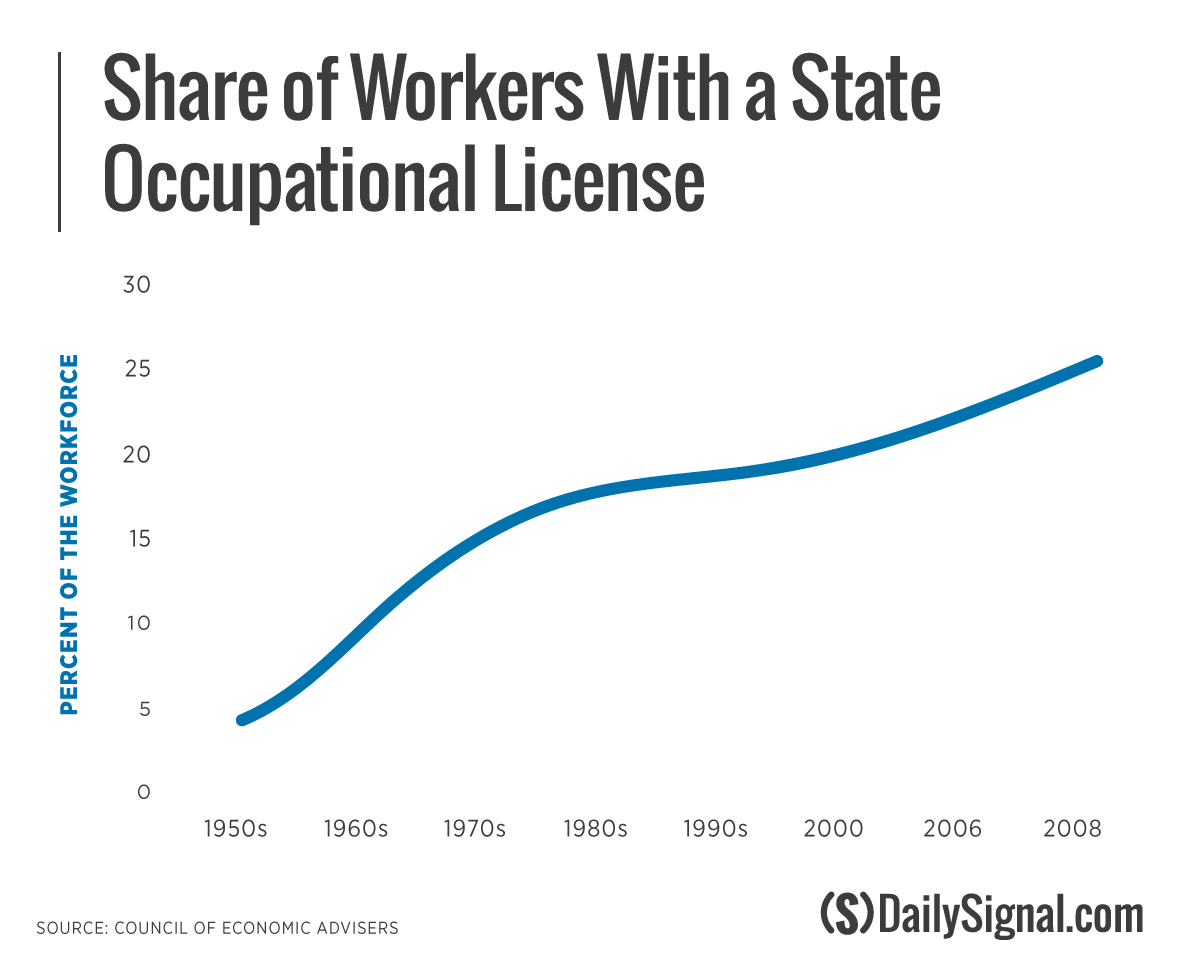

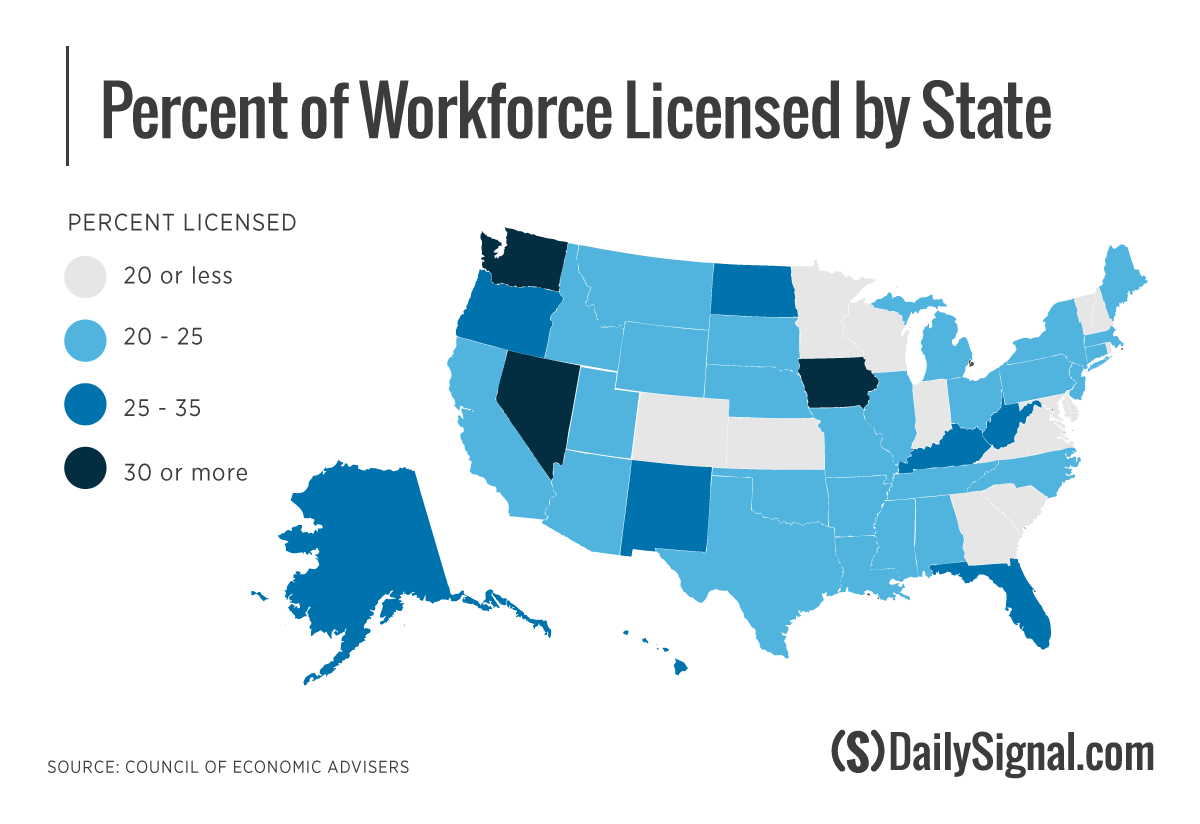

According to a study released by the Obama administration in July, the percentage of the workforce covered by state licensing laws grew from less than 5 percent in the 1950s to 25 percent in 2008.

Two-thirds of that change is related to an increase in the number of professions that require a license, the report found.

The number of occupations requiring licenses across all 50 states range from a high of 71 in Louisiana to a low of 24 in Wyoming, according to a 2012 report from the Institute for Justice, a public interest law firm.

The group found a couple of the most frequently licensed occupations are pest control applicators and emergency medical technicians, licensed in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. In contrast, forest workers and florists are licensed in just one state each.

Shampoo technicians, meanwhile, are licensed in four other states besides Tennessee: Alabama, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and Texas.

The White House, along with a bipartisan group of lawmakers on Capitol Hill, has started a push to encourage states to roll back occupational licensing laws, which this unofficial coalition argues make it difficult for workers to enter various fields and can hurt wages for those excluded.

“Licensure makes it really hard to try something,” Salim Furth, a research fellow in macroeconomics at The Heritage Foundation, told The Daily Signal. “If you’re committed to a career, it’s not that big of a barrier. But what if you want to try something, or you need some income while you’re in between jobs? Those kinds of workers, especially young workers, are being told you have to choose to make this a career. You can’t just try it out.”

Additionally, licenses rarely are recognized across state lines, which disproportionately affects military spouses.

In Tennessee, cosmetologists and barbers are regulated by the state Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners. The board is comprised of 14 members, and 12 of its members work in the cosmetology and barber industries, as required by law. The remaining two are members of the public.

The issue of state boards overseeing licensing requirements has been met with resistance, and economic experts warn that such boards often exist to block competitors from entering markets.

“You have a board of market participants passing anti-competitive legislation,” Boucek said of the Tennessee Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners.

Furth said state boards often begin to “creep” with the number of occupations they regulate.

“Once you get a board in place to do something that might have commonsense value, that board has an incentive to keep broadening their power and expanding things under their control,” Furth told The Daily Signal.

So far this year, state legislatures in Nebraska and New Jersey have passed legislation rolling back some of the regulations governing different occupations. Delaware’s governor, meanwhile, signed an executive order last month creating a committee to review licensing regulations.

Despite the action in state houses, Furth said the best chance for a permanent solution comes with how the courts are instructed to deal with economic freedom.

“We need to fundamentally change the way we think about economic freedom,” he said. “This is a basic right. This is a right to go into the marketplace, to truck, barter, and exchange. To work, to improve oneself. That’s a foundational human right, and any government that seeks to narrow or prescribe that should have to meet a high burden of proof.”

“It’s a general principle that who’s making the law here wasn’t the Tennessee Legislature saying we need to keep Americans safe from bad smelling shampoo,” Furth said. “It’s some board saying, ‘We can push down competition and push down wages by making it illegal to hire people.’”

Steep Penalties for Licensing Violations

The Tennessee Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners employs between 15 and 18 “field inspectors” hired to inspect barber and cosmetology schools and shops for proper sanitation and unlicensed activity. Under authority established by the board, its legal division has the power to issue consent orders for unlicensed activity.

For a salon worker caught without a license, the consequences can be costly.

In April 2014, for example, inspector Jerry Biddle entered a Memphis salon to conduct a “lawful inspection of the premises therein” and saw a manicurist shampooing a client’s hair, according to a report he filed with the state.

The manicurist didn’t have the license allowing her to shampoo hair, Biddle wrote in his notice of violation, and was therefore running afoul of Tennessee law.

Robert Herndon, a lawyer with the Tennessee Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners, sent the manicurist a letter regarding the violation and offered her a deal: pay a $250 penalty or face formal disciplinary charges and attend a hearing before an administrative law judge.

Disciplinary proceedings, Herndon continued, could result in up to $1,000 in fines and a loss of the manicurist’s license.

“There are floors in government buildings filled with people whose jobs are to [find unlicensed activity],” Boucek said. “Investigators who go out and police this stuff, people with law enforcement authority.”

Walters, of the state Department of Commerce and Insurance, said there currently aren’t any complaints filed against shampoo technicians.

A ‘Sense of Worth’

Over the course of her lifetime, Nutall estimates she’s taught thousands of women across the country her technique of hair braiding, including her sister, daughter, and granddaughter, Leanna.

Nutall said she became involved in the lawsuit because of the family members like Nutall-Pritchard and Malone who would love to open up their own natural hair care salons, just as she did more than 20 years ago.

“They just can’t because of the laws, which is crazy to me,” she said. “Everybody has a right to earn a living.”

For Nutall-Pritchard, she feels the government is hypocritical, particularly when it comes to the future successes of young women.

“They want to get these young women off welfare,” she said, “but how are they going to get off welfare when you’re making it so hard with a simple trade as shampooing?”

Regardless, Nutall holds out hope that the state will come around and make it easier for young women like her granddaughter to earn a good, honest living, just as she was able to do.

“I would like to see these young people able to braid hair or to shampoo hair or to cut hair, able to do this and then earn a living out of it,” she said. “Give them something to stabilize them. Give them a sense of worth. When you work for something, you’re more proud of it because it came from your own loins. You did this.”