Pressure from government officials and eminent researchers appears to have pushed a federal agency to postpone enforcement action on violations it found in a government-financed experiment on extremely premature babies.

The agency, which polices ethics in health studies, says the controversy over the study of preemies highlights a “fundamental difference between the obligations of clinicians and those of researchers.”

That ethics body, called the Office for Human Research Protections, is part of the Department of Health and Human Services. The sponsor of the controversial experiment, the National Institutes of Health, is also part of HHS. Officials at both HHS and NIH provided “input” leading to the office’s delay in enforcement.

>>> Part 2 of 3: The ethics of the individual good and the greater good. Read Part 1: Did government’s experiment on preemies hide risks?

At issue is SUPPORT, a study in which researchers at two dozen academic institutions randomly manipulated the oxygen levels of 1,316 extremely premature infants without providing their parents the full details of the methods and risks.

The view of the HHS ethics office, directed by Dr. Jerry Menikoff, is that although medical doctors act in the best interest of individual patients, researchers do not.

Rather, researchers focus on what they consider the greater good. But as a trade-off, researchers must tell study participants about all the risks.

Dr. Michael Carome, a senior leader in the HHS ethics agency before joining the consumer watchdog group Public Citizen in 2011, is among critics who suggest SUPPORT researchers overlooked risks to induce parents to sign up.

Public Citizen’s Michael Carome speaks last summer outside HHS headquarters. (Photo: Angela Bradbery)

Before the multiyear study, Carome says, the link between lower oxygen and death in preemies already was well known to researchers and widely published—and should have been disclosed to the study parents.

“Too often, there’s a tremendous tendency to minimize risks, overstate benefits, and downplay the experimental nature of research either unknowingly or intentionally to try to make sure you can recruit subjects quickly and complete the experiment,” Carome says.

Researchers conducted the SUPPORT study, which cost taxpayers $20.8 million, from 2005 through 2009. The acronym stands for “Surfactant, Positive Airway Pressure, and Pulse Oximetry Randomized Trial.”

SUPPORT scientists and their advocates are adamant that the risk of death for the preemies was unforeseeable.

“We have adhered to the highest ethical principles, and we will continue to work to ensure that known potential risks are described in our consent forms,” Dr. Waldemar Carlo, the lead researcher, wrote last year to the New England Journal of Medicine, which published the study in 2010.

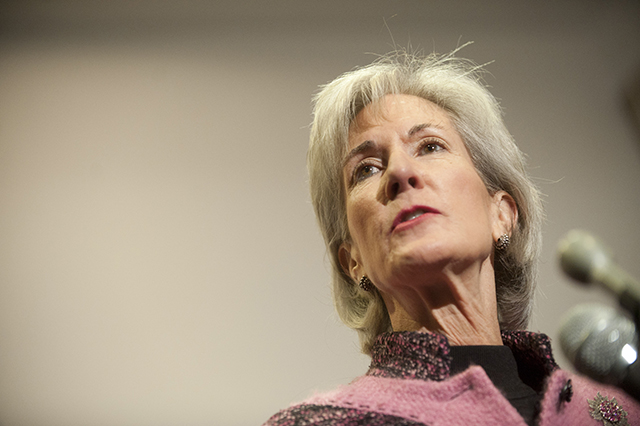

In an April 2013 letter to HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius, however, Public Citizen demanded that the government address alleged ethical lapses and apologize to the study families. In a follow-up letter Jan. 27, the liberal-leaning watchdog group said the design of the study was unethical because it lacked a control group to compare with the study babies and failed to adequately monitor their safety.

Government vs. Government

The entire dispute might be little more than an academic debate if it weren’t for one crucial factor: The Office for Human Research Protections, the ethics body within HHS, ruled that the consent process for the study violated federal regulations designed to protect human research subjects.

Public Citizen wants answers from HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius (Photo: Pete Marovich/ZumaPress.com/Newscom)

“The consent was significantly deficient,” Menikoff, director of the ethics office, says.

His office sent a stern letter to SUPPORT researchers on March 7, 2013 stating consent forms signed by parents of the preemies “failed to describe the reasonably foreseeable risks of blindness, neurological damage and death.”

It was a bombshell.

One agency within HHS, the ethics office, had slapped another, NIH, with a formal ethics violation. This unleashed a torrent of pushback.

Little more than three months later, the ethics office appeared to back down. In a follow-up letter, it formally suspended corrective action or punishment.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that intense political pressure was brought to bear” from an academic research establishment that is dependent on the government, Carome says, and that senior leadership at HHS “bowed” to it. Having previously worked in the ethics office for 13 years, the director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group is familiar with agency politics.

‘Adverse Implications for Research’

Internal government emails recently obtained by Public Citizen through a Freedom of Information Act request only add fuel to suspicions of political interference.

Bioethicist Ruth Macklin, a professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, says the emails strongly suggest that NIH officials “launched an aggressive campaign to undermine” the ethics investigation into the SUPPORT test— “and regrettably found several willing partners for this campaign at the highest levels” of HHS.

The emails show that, as senior NIH officials were trying to tamp down the ethics probe, they also were orchestrating a defensive commentary to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine last June.

Meanwhile, 45 research scholars and ethicists exerted additional pressure on the ethics office in a separate letter, urging that the agency withdraw its finding of a violation. “We believe that this conclusion was a substantive error and will have adverse implications for future research,” they wrote.

Two weeks ago, on May 20, Public Citizen and nine prominent scholars called on the HHS Office of Inspector General to investigate whether officials at NIH and HHS improperly interfered with the ethics body’s probe of the experiment on preemies.

In a statement, HHS said: “In the process of drafting its follow-up letter, OHRP [the ethics body] received input from HHS leadership, as well as NIH.”

An HHS spokesman would not directly answer last week when asked whether senior officials improperly intervened to convince the ethics office to suspend corrective action or punishment. Instead, the spokesman said the office’s original finding of a violation was made independently.

Lessons of Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

Modern rules for research on humans were forged after the U.S. government’s Tuskegee syphilis experiment on black men in 1932 entitled, “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” For 40 years, test subjects weren’t told they were part of a study, nor were they treated for their syphilis even after penicillin was determined to be a cure in 1947.

When a series of Associated Press reports exposed the study in 1972, an outcry led to new rules intended to prevent a repeat of the Tuskegee mistakes. Those rules mandate voluntary, informed consent from all human test subjects.

The once-secret Tuskegee syphilis experiment shaped research ethics. (Photo: National Archives via Wikimedia)

As part of the consent process, scientists must tell participants about the risks of the studies and get their written consent. Additionally, special panels of experts called Institutional Review Boards at universities and other facilities conducting the studies must approve the designs and consent forms.

Now, 42 years after the Tuskegee experiment ended, the NIH-funded study of preemies has reopened painful wounds and raised questions about whether protections for human test subjects are fundamentally flawed. More than 20 Institutional Review Boards at prestigious facilities such as Duke University Hospital and Yale University School of Medicine had approved the study and consent forms.

How could they all have made, in the opinion of the HHS ethics office, such critical errors?

“I don’t think this is ethically as troubling, as bothersome, as many of the critics do,” says Arthur Caplan, a noted ethicist at NYU who defends the SUPPORT researchers.

‘A Little Bit of the Unknown’

Caplan argues that the study babies had the same “standard of care” as the non-study babies because their oxygen levels never deviated from the generally accepted range. The study posed minimal risk, he says, because it was merely “fine-tuning” a treatment rather than testing an experimental drug or brand new treatment.

“If SUPPORT is truly a study involving accepted standard of care, then there is a low bar for informed consent,” Caplan says, adding: “In health care, each one of us is a little bit of a subject whether we like it or not. There’s always a little bit of the unknown and there’s always a little bit of research behind every medical intervention.”

In his letter of defense, Carlo, the lead SUPPORT researcher, wrote: “Ill-informed allegations create unwarranted apprehension that serves no one. We provided parents with the information known at the time, which did not indicate an increased risk of death resulting from assignment to either treatment group.”

Also defending the study and his agency’s role in it is Dr. Alan Guttmacher. He leads the branch of NIH that approved and funded SUPPORT: the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network.

Guttmacher argues that the experiment added to the body of knowledge on the subject and already has helped in the treatment of other preemies.

“We stand by this study as it was conducted and look for ways to do research even better, if there is a better way to do it, in the future,” the NIH official says.