It’s common for Americans on July 4th to read and discuss the Declaration of Independence, and to reflect on its principles and ideas. Those principles and ideas are often attributed solely — though wrongly — to Thomas Jefferson, the primary author of the draft of the Declaration.

Jefferson’s draft was modified in two stages: First, by a “Committee of Five” composed of Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston, and second by the entire Continental Congress.

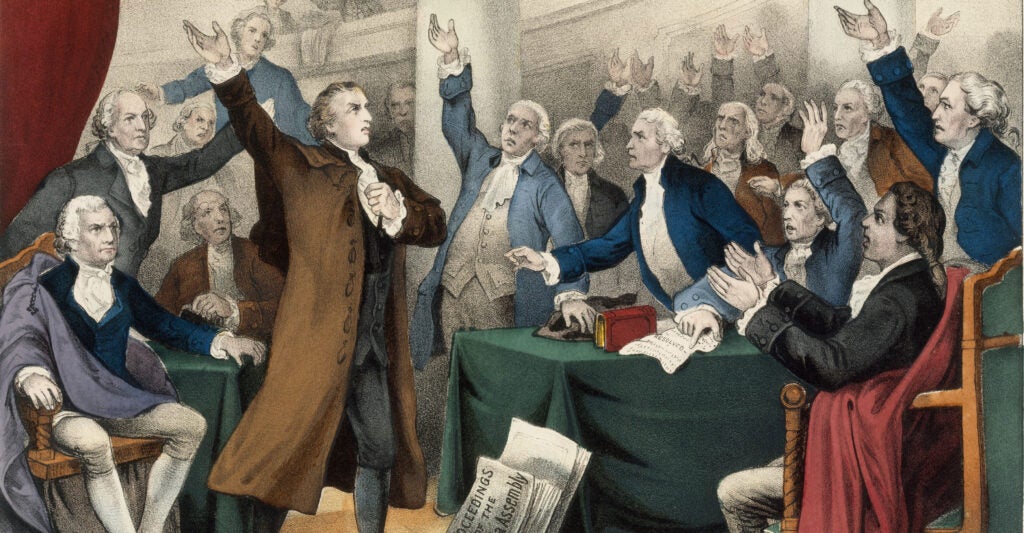

The Congress discussed Jefferson’s draft for three days, and made significant changes (according to Jefferson, “depredations”) to his work.

In short, the Declaration was the work not of a single person, but of the representatives of the American people. Jefferson was the author of the draft, but it was an American Declaration.

It was, as Jefferson would later explain, “an expression of the American mind.” As Jefferson implied, the Declaration of Independence merely declared, in condensed form, the political ideas that had become consensus among the Colonists over the course of many years.

Consider the document that inspired the Declaration of Independence: the Virginia Declaration of Rights, penned primarily by George Mason and adopted by Virginia’s Constitutional Convention in June of 1776, a few weeks before the Declaration of Independence was written.

Though it’s largely overlooked today, much of the Declaration was drawn from Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights. When Jefferson wrote the draft of the Declaration of Independence, he had two documents next to him: a draft constitution of Virginia and the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights’ most obvious influence on the Declaration of Independence is found in the beginnings of each document. The first section of the Virginia Declaration of Rights asserts the principle of natural rights using language similar to the Declaration of Independence:

That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

When celebrating the Declaration of Independence every July 4th, we should also celebrate the document that inspired the Declaration.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights helps us to understand the principles of the Declaration more clearly. For instance, Jefferson did not mention the right to “property” in the Declaration, but that doesn’t mean the Founders rejected a natural right to property.

The Virginia Declaration specified that, in addition to the rights to life and liberty, human beings have an inherent right to “the means of acquiring and possessing property,” as well as “pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

Mason included the right to the pursuit of happiness, but he also emphasized the right to acquire and possess property.

People often focus on the right to “possess” property, but overlook the right to “acquire” property. As author and Hillsdale College politics professor Thomas West has recently argued, it’s not enough for government to protect the property that people already own. There must also be an opportunity to acquire property, so that the poor as well as the rich benefit from the fruits of their labor.

Though the Virginia Declaration of Rights emphasizes the right to property, it emphasizes the right to acquire property, thus ensuring that property rights allow all to pursue happiness.

In short, the Declaration of Independence is heavily indebted to the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which preceded it by less than a month. We deepen our understanding of the principles of the Declaration by reading it alongside the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

The Continental Congress’s debt to the Virginia Declaration of Rights was so significant that, as he neared the end of his life, Jefferson had to address claims that the Declaration of Independence was unoriginal.

Jefferson admitted that the Declaration of Independence was not original. He wrote to James Madison that, when writing the draft, “I did not consider it as any part of my charge to invent new ideas altogether and to offer no sentiment which had ever been expressed before.”

His partner on the “Committee of Five,” John Adams, agreed. He wrote that “there is not an idea in [the [Declaration], but what had been hackney’d in Congress for two years before.”

When we celebrate Independence Day on July 4th, we celebrate the Founders’ expression of the American mind. The American mind is not found in the thoughts of a single individual, such as Jefferson, but in the public philosophy contained in the documents that set forth their first principles.

Those first principles are found not only in the Declaration of Independence, but in important documents that inspired it, such as Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights.

Happy Independence Day!

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.