“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” On July Fourth, we celebrate much more than our independence from Great Britain. Our Founding Fathers risked their lives and reputations in the American Revolution to establish a government based on universal, permanent principles of justice.

At the core of these principles was the claim of human equality. By equality, the Founders did not mean all humans possessed the exact same number or level of talents, virtues, or vices. Instead, they declared three basic truths flowing from and describing human equality.

First, humans are equal in their natural rights, those “endowed by their Creator.” Different persons may do more or less, better or worse with their “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” But they each possess these rights against any contrary action taken by a government or another man.

Second, human equality meant that no man could rule over another without the first one’s consent. The right to liberty entailed that slavery held no moral claim.

Third and finally, human equality meant the law must provide the same protections and impose the same penalties to all, not creating arbitrary distinctions of class, race, or any other factor.

Though Jefferson asserted its self-evidence, American history has not perfectly realized this principle of human equality. We began our nation with race-based slavery already in existence, an institution many fought but which remained stubbornly resilient until the Civil War. After the Civil War ended the institution, the scourge of segregation and race-based violence continued well into the 20th century. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s tore down these structures, too.

This past week added yet another triumph for human equality in the Supreme Court’s affirmative action decision. By a 6-3 vote, the court struck down race-based policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. The majority’s reasoning, if followed, renders almost any use of race invalid at state colleges and those accepting government funding.

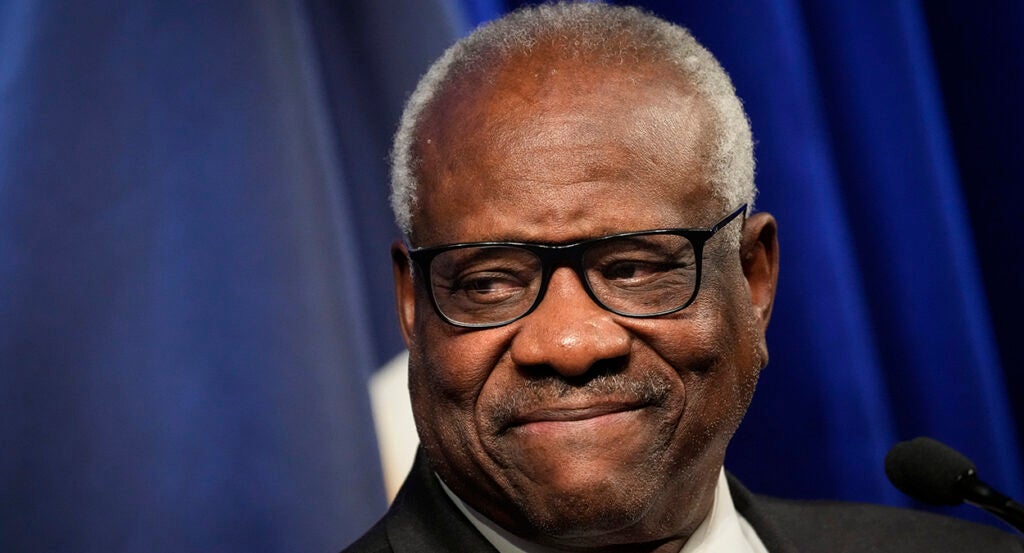

This Fourth of July, Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion is a fitting read. Thomas, who has championed last Thursday’s outcome for decades, exalted that, “despite a lengthy interregnum, the Constitution prevails.” His opinion cut to the heart of what was at stake in the affirmative action cases. He traces the history of America’s struggle to realize human equality, showing how Thursday’s opinion is another step toward that founding goal.

Thomas fully admitted the problem of our founding: “The great failure of this country was slavery and its progeny.” He then showed how the amendments resulting from the Civil War—the 13th, 14th, and 15th—sought to realize the three manifestations of equality the Founders had intended, but not fully followed, in the declaration.

He showed how those additions to the Constitution intended to secure a real avenue for consent in voting rights. More important to this case, he described in detail how those amendments were intended to pursue equality before the law regardless of the color of one’s skin.

In making that point, Thomas also pointed to the third declaration goal: securing rights.

Legal equality should protect two kinds of rights. The first, civil rights, are largely those natural rights inherent in all humans and for which the declaration said government was instituted to protect.

The second, political rights, including rights related to citizenship. As all men were created equal by God, so the Constitution must treat all Americans as equal, both in their humanity and in their citizenship.

Together, these amendments were supposed to secure what Justice John Marshall Harlan said in dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson: a “color-blind” Constitution. Thomas celebrated the court’s vindication of this principle in the dismantling of racial segregation, a judicial undertaking that began with Brown v. Board of Education.

But Thomas also recounted how the rise of affirmative action, even if well-intentioned, was a step back from this slow, gradual, progress. It scuttled the idea of a colorblind Constitution in pursuit of goals such as diversity and remedying the past or present societal discrimination. But doing so meant picking winners and losers based on the color of one’s skin. It meant affirming old stereotypes or trying to create new ones. And, as Thomas has said repeatedly, using racial categories in the law “demeans us all.”

Though Thomas acknowledges continuing struggles for our society regarding perfect racial equality, he ends his opinion with optimism: “I hold out enduring hope that this country will live up to its principles so clearly enunciated in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States: that all men are created equal, are equal citizens, and must be treated equally before the law.”

This Independence Day, let’s follow Thomas in better understanding the declaration’s principle of human equality and celebrating last week’s victory for that principle. May we dedicate ourselves to continuing our country’s striving, that this self-evident truth will become our self-fulfilled one.

The Daily Signal publishes a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Heritage Foundation.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.