Arguing for keeping “presentism” out of history seems like a straightforward argument from an acknowledged history scholar, right?

Wrong. Not these days.

The president of the American Historical Association, James H. Sweet, published an essay last week arguing that scholars should bar “presentism” from history.

Sweet’s column in the American Historical Association magazine, Perspectives on History, argued that “doing history with integrity requires us to interpret elements of the past not through the optics of the present but within the worlds of our historical actors.”

Pretty basic stuff.

Shortly thereafter, Sweet was mobbed by those who clearly didn’t like his perspective, then issued what looked like a forced confession for his crime.

The whole episode demonstrates how American and other Western institutions have been wholly radicalized in a short amount of time, squandering their reputations and authority.

Here’s how it went down.

The American Historical Association president argued that academic historians should focus simply on bringing to life the world of people in the past as it was and as they saw it, instead of framing every historical person or event through a modern “social justice” lens.

Sweet laid out the problem, which he said is transforming the profession of historian:

This trend toward presentism is not confined to historians of the recent past; the entire discipline is lurching in this direction, including a shrinking minority working in premodern fields. If we don’t read the past through the prism of contemporary social justice issues—race, gender, sexuality, nationalism, capitalism—are we doing history that matters? This new history often ignores the values and mores of people in their own times, as well as change over time, neutralizing the expertise that separates historians from those in other disciplines.

For an example of this, I’d point to the recent book “The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe,” written by two history professors. The book devotes much space to debunking “whiteness” and ambles through the history of the Middle Ages making often factually dubious evaluations and value judgments of people and events from over a millennium ago.

This is becoming the norm, especially for social history, not the exception.

Here’s the part that really got Sweet into hot water. While making his argument, he offered a rather mild critique of The New York Times’ 1619 Project, writing that the reimagining of U.S. history “spoke to the political moment,” but he “never thought of it primarily as a work of history.”

That’s a rather tepid way of describing the 1619 Project.

The Times’ endeavor was full of inaccuracies and ahistorical revisionism. Its essays were shredded by historians and writers across the political spectrum, from some of my colleagues at The Heritage Foundation to the World Socialist Web Site.

Sweet also took issue with the increasing description of slavery as a problem unique to the United States. He noted how most of the trans-Atlantic slave trade was in Brazil and the Caribbean, and wrote that it was historically problematic to whitewash the prominent role that African nations played in promoting the slave trade.

Sweet threw a few obligatory shots at the right, perhaps to assure the left-wing ivory tower that he was being balanced in his piece and that the real villains are on the right.

It didn’t work.

The essay didn’t go over well with the apparently all-powerful woke left. Sweet’s generous description of the 1619 Project as not really history and his inclusion of a fuller historical record was too much for activists masquerading as historians in the academe.

After a few days of nonstop frothing from academics on Twitter—and undoubtedly much more out of the public eye—Sweet added a long, groveling apology to the top of his article.

He wrote that his gentle rebuke of presentism and politicization of history caused “harm to colleagues, the discipline, and the [American Historical] Association.”

It’s a hallmark of woke activists to claim that arguments they don’t like cause “harm” just before they censor them. The “words are violence” school of thought apparently is universally accepted now among our ruling class clerisy.

The ridiculous apologies went on and on. Here’s more of Sweet’s cringing prose:

I sincerely regret the way I have alienated some of my Black colleagues and friends. I am deeply sorry. In my clumsy efforts to draw attention to methodological flaws in teleological presentism, I left the impression that questions posed from absence, grief, memory, and resilience somehow matter less than those posed from positions of power. This absolutely is not true. It wasn’t my intention to leave that impression, but my provocation completely missed the mark.

The American Historical Association then locked its Twitter account. When it unlocked the account, the association issued an additional apology, blaming the incident on “alt-right trolls.”

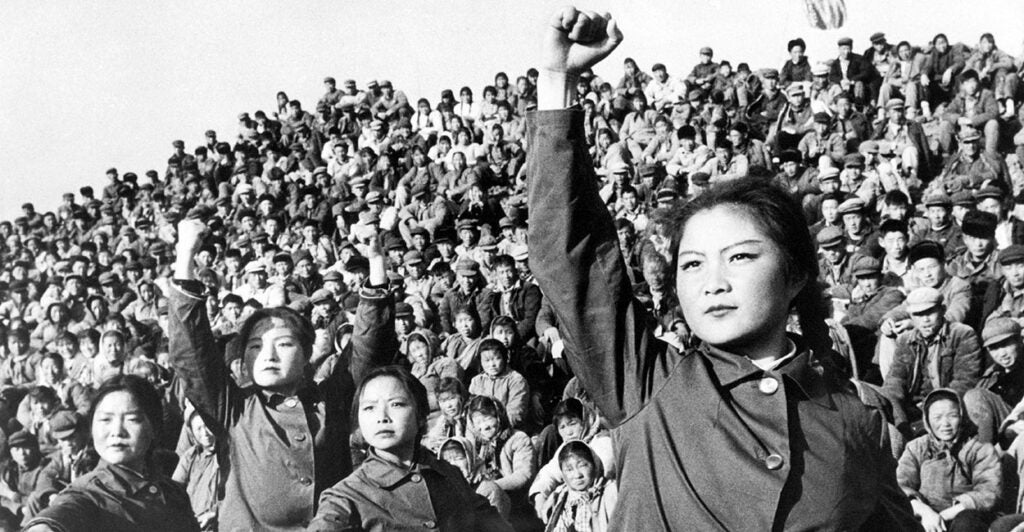

The episode—to make a historical comparison—seemed to be a modern, Americanized version of a Maoist struggle session.

It’s not just that leftists responded hysterically to Sweet’s piece, but they apparently have so much power over the American Historical Association that, in effect, they can force the group’s president to issue cringing apologies at the snap of their fingers.

Shall we put a dunce hat on the professor and allow the mob to throw insults and rotten fruit at him, too?

It’s just the latest example of how institutions in America have been rapidly and totally captured by radical, left-wing revolutionaries. The response to the over-the-top opposition to Sweet’s piece should have been an offer to debate or publish another view at the most.

And if that didn’t work, Sweet’s ridiculous critics should have been told to get bent.

That didn’t happen and a struggle session ensued.

Imagine how different things would be if institutions and bureaucracies had just said “no,” or refused to comply with extremist demands? Because even the slightest resistance has been removed, we are left with situations where, for instance, a small tribute to Abraham Lincoln is removed at a university because a single person complained about it.

Our institutions, public agencies, corporations, and professional organizations are becoming both highly censorious of dissent from the dominant “narrative,” while also allowing woke Twitter mobs and campus activists to dictate their policies.

In one sense, Sweet was correct in his apology. His words did cause “harm.” The fact that he apologized to the mob indicates how the history profession and America’s elite organizations and institutions have been totally compromised and radicalized.

As activists and mobs tore down historical statues that they found offensive, one response from the “measured” left was that offensive history and statues should be removed from public display and placed in a museum. You know, for “context.”

But do you trust organizations such as the American Historical Association or James Madison’s Montpelier—which now aligns with the Southern Poverty Law Center—to provide faithful and accurate representations of the past?

Perhaps the way forward is to keep history in the public eye and out of the clutches of ideologically one-note institutions that are fanatically obsessed with, as Sweet wrote, “race, gender, sexuality, nationalism, capitalism.”

It is with the people and alternative institutions that we should place our trust.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.