President Joe Biden announced Monday that the United States had killed al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahri in a drone strike over the weekend.

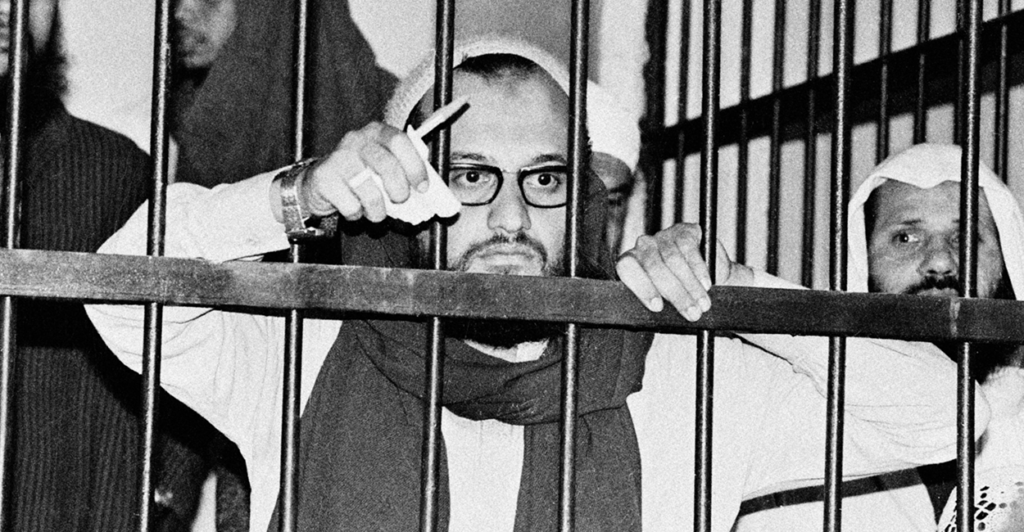

Zawahri, who was an Egyptian doctor, replaced Osama bin Laden after he was shot and killed by U.S. Navy SEALS in May 2011. He was listed as the FBI’s “Most Wanted Terrorist” and helped to plan the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

“Zawahri has been a high-level target of the United States, one of the most wanted people in the world for over 20 years,” Jeff Smith, a research fellow in the Asian Studies Center at The Heritage Foundation, says. (The Daily Signal is Heritage’s multimedia news organization.)

Smith joins a bonus episode of “The Daily Signal Podcast” to discuss the significance of Zawahri’s death, the future of al-Qaeda, who might replace him, and counterterrorism operations in the Middle East.

Listen to the podcast below or read the lightly edited transcript:

Samantha Renck: Joining the podcast today is Jeff Smith. He is a research fellow here at The Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center. Jeff, thank you so much for joining me today.

Jeff Smith: It’s great to be with you.

Renck: Now, President Joe Biden announced Monday that the United States had killed al-Qaeda leader Ayman Zawahri in a drone strike July 30, ending a 21-year manhunt. So, first and foremost, Jeff, who exactly was Zawahri and what is the significance of his death?

Smith: Well, he was widely considered to be Osama bin Laden’s deputy and was then al-Qaeda’s No. 2 in command and responsible, frankly, for the planning and operation of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Zawahri has been a high-level target of the United States, one of the most wanted people in the world for over 20 years.

His terrorist activities predated 9/11, and he’s an educated Egyptian who went on to join the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan alongside bin Laden and the two gradually developed al-Qaeda into one of the world’s most notorious terrorist outfits.

Zawahri has since been hiding, likely somewhere inside of Pakistan, releasing videos periodically, urging global jihad, you know, expressing extremist sentiments.

And U.S. intelligence caught wind that Zawahri’s family had moved into Afghanistan in the capital, Kabul, earlier this year and later confirmed that he was also on the premises. And when they found an opportunity to strike, they took it.

Renck: And now what is the future of al-Qaeda? Is there someone who is next in line to essentially replace him?

Smith: There’s always a next in line. Al-Qaeda does continue to enjoy some influence both in the [Afghanistan-Pakistan] region and globally. But really, it’s become part of this broader mixture of terrorist groups that operate in the region, alongside of the Taliban, alongside of the Haqqani network, both of which are now in control of Afghanistan, both of which are aligned with al-Qaeda.

You also have factions of the Islamic State in Afghanistan, which are aligned with this nexus, and they sort of are all in some ways integrated with one another.

And so I would say the capabilities of al-Qaeda central have certainly been downgraded since 9/11 through an exhaustive drone campaign in Afghanistan, in Pakistan’s tribal areas. We’ve sort of whittled away their leadership and much of their rank and file, but they do continue to operate within this broader nexus of terrorist groups.

And the bigger concern, frankly, is that since the withdrawal from Afghanistan under the Biden administration, the Taliban and Haqqani network now running Afghanistan, the concern is that they’re going to offer a more permissive environment to al-Qaeda and these other international terrorist groups.

And the presence of Zawahri in a posh neighborhood in the Afghan capital, living in a guesthouse run by Siraj Haqqani, who is a major Taliban leader, suggests that those fears were correct, and it’s already evident that they’re providing space for al-Qaeda to operate. So this is a very concerning trend.

Renck: And speaking of the fall of Afghanistan, and we’re coming up on that one year of the Taliban takeover there, what do you think is the future of counterterrorism ops in the Middle East given Iran’s growing aggression and also the Afghanistan withdrawal?

Smith: I guess, in a way, we got some good news and some bad news out of this operation. And the good news is that we are still capable of launching airstrikes inside of Afghanistan.

And one of the questions, frankly, many of us have is how exactly was this operation carried out? Was Pakistan used either as a launching pad or did we use its airspace? And if so, did we have its permission to do so or did we launch the raid without its permission?

You might recall that we launched a raid against Osama bin Laden, found inside Pakistan less than a mile from a premier Pakistani military academy. We launched that operation into Pakistan without their permission.

In this case, it’s also possible the drone flew in through Central Asian countries.

The point is, though, that we do have limited access now after withdrawing; we don’t have nearly as many boots on the ground, eyes on the ground, and ways to launch these types of operations. But clearly we do maintain some capability.

Whether that capability is enough to match the likely growing threat of terrorism coming from Afghanistan is a different story. And we’re going to have to find new arrangements in the future to do these counterterrorism operations.

One of my biggest issues with the Afghanistan War was that we sort of allowed Pakistan to play this double game where they let us use their territory and airspace. But the entire time they were supporting, defending, and protecting the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

So we have to avoid getting into a similar type of arrangement where we’re sort of perpetuating the long-term problem.

Renck: Thank you so much for joining the podcast today. Again, joining us today was Jeff Smith of the Asian Studies Center here at The Heritage Foundation. Thanks again.

Smith: Thank you.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com, and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.