For nearly 100 million American workers waiting breathlessly for an answer, a Thursday Supreme Court decision delivered good news for many, although not all.

In a rare late-day release of opinions, the Supreme Court issued its rulings in a pair of federal vaccine mandate cases that went to the court on an emergency basis.

In the first case—anticipated to have applied to approximately 84 million employees—and by a 6-3 vote, the Supreme Court in National Federation of Independent Business v. OSHA stayed the implementation of the vaccination mandate that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration had issued in November 2021, requiring all businesses with 100 or more employees (with very limited exceptions) to direct their employees be vaccinated against COVID-19 or wear a mask at work and provide weekly negative tests for the disease.

In an unsigned opinion, the majority concluded that the government was not likely to prevail on its argument that OSHA possesses the authority to issue the vaccination mandate. It wrote that neither OSHA nor Congress had ever imposed such a requirement and that, “although Congress has enacted significant legislation addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, it has declined to enact any measure similar to what OSHA has promulgated here.”

“As its name suggests,” the court explained, “OSHA is tasked with ensuring occupational safety—that is, ‘safe and healthful working conditions.’” That means OSHA is only empowered “to set workplace safety standards, not broad public health measures,” and according to the justices, “no provision of the Act addresses public health more generally, which falls outside of OSHA’s sphere of expertise.”

The court classified the COVID-19 virus as not an “occupational hazard,” but a “universal risk” that “is no different from the day-to-day dangers that all face from crime, air pollution, or any number of communicable diseases.”

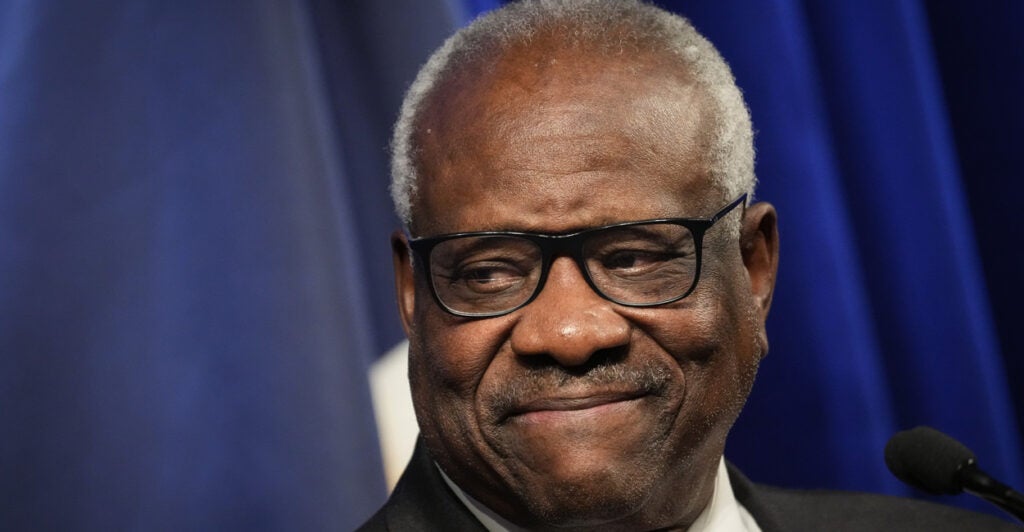

Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, filed a concurring opinion. He emphasized that under the court’s “Major Questions Doctrine,” the court will not presume that Congress empowered an agency to resolve a question of broad economic or social policy without expressly authorizing in the statute’s text the authority to do so. The Occupational Safety and Health Act, he concluded, grants OSHA no such power.

Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, dissented. Breyer concluded that because “COVID-19, in short, is a menace in work settings,” as proved by the number of people it has sickened or killed, OSHA could adopt a vaccination or mask-and-test requirement for businesses.

The Daily Signal’s parent organization, The Heritage Foundation (which had filed an application with the Supreme Court to halt the OSHA mandate), reacted to the news Thursday. Heritage President Kevin Roberts trumpeted the victory in a public statement, saying:

The federal government has no business dictating the private and personal health care decisions of tens of millions of Americans, nor does it have the authority to coerce employers into collecting protected health care data on their employees. By striking down the Biden regime’s unlawful COVID-19 vaccine mandate, the Supreme Court has signaled its agreement with this basic tenet of a well-functioning and free society.

While the OSHA mandate is stayed for now, litigation on the merits of the government’s employer vaccine rule will continue in the lower court (the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals).

In its second opinion of the afternoon, the court—in Biden v. Missouri, another unsigned opinion, but this time, by a 5-4 vote—allowed the Department of Health and Human Services’ vaccine mandate (administered through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) for workers at federally funded health care facilities to take effect.

The court wrote that a global pandemic “provide[s] no grounds for limiting the exercise of authorities the agency has long been recognized to have.” It noted that as a condition of receiving federal funds, Congress authorized the secretary to promulgate such “requirements as [he] finds necessary in the interest of the health and safety of individuals who are furnished services in the institution.”

The court noted that it would be the “very opposite of efficient and effective administration for a facility that is supposed to make people well to make them sick with COVID-19.” It also concluded that the vaccine rule was not, as the states had claimed, arbitrary and capricious, and that the longer, more complicated notice-and-comment period as required by the Administrative Procedure Act (ensuring transparent rule-making from the federal government) would have been impossible.

Thomas, joined by Gorsuch, Alito, and Justice Amy Coney Barrett, dissented, saying that the statutory provisions relied on by the government did not support its vaccine rule.

The justices noted that those provisions direct the “administration” of Medicare and Medicaid and are those that serve “the practical management and direction” of those programs, but there was no connection to that administration and a rule requiring “millions of healthcare workers to undergo an unwanted medical procedure that cannot be removed at the end of the shift.”

Thomas wrote that the government had a shaky foundation for its virtually unlimited vaccination through the Department of Health and Human Services, and if Congress had wanted to grant the agency the power to impose a vaccine mandate across all facility types and upset the state-federal balance (because only the state possesses the police power to mandate vaccination), it would have specifically authorized one.

In both cases, the question before the court was not how to respond to the pandemic, but who holds the power to do so.

For now—and until the litigation in the appellate courts below comes to an end—the answer is clear.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.