As a millennial woman, I read Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” for the first time with a sense of familiarity. It was familiar not only because I recognized in it the feminist arguments of today (many credit the work for launching the second wave of feminism) or that I recognized certain women I have known in its pages.

Rather, it was familiar because it reminded me of a work published over a hundred years before its time: “Madame Bovary.”

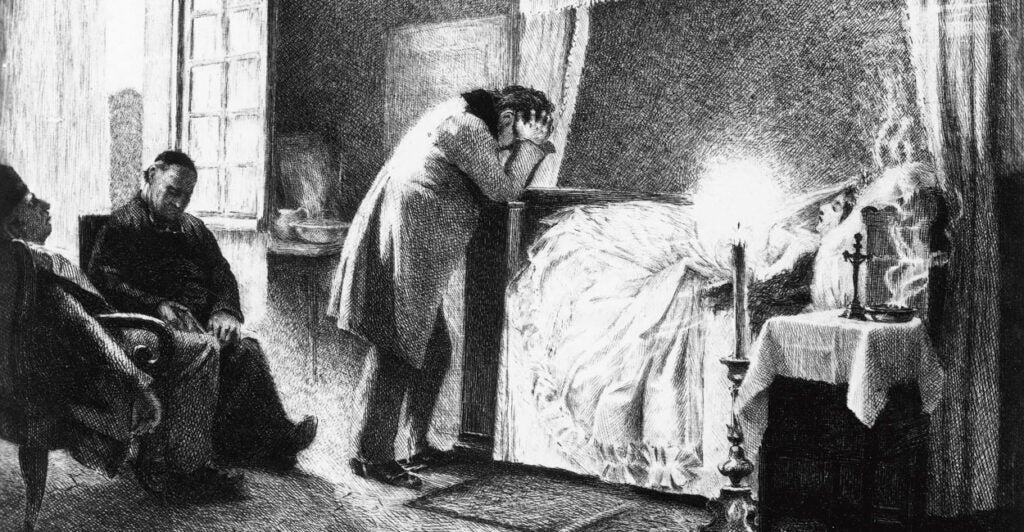

The French classic is a tale of a beautiful and charming woman who marries a dull but decent country doctor. Emma Bovary is perpetually restless and distasteful of the ordinary.

She longs for the romanticism detailed in her dog-eared novels and becomes corrupted by their ideology. Emma’s virtues, like her desires, prove illusory.

Friedan’s work is a series of accounts and analysis of the 1950s middle- to upper-class American housewife: lonely, bored, and discontent. Modern technologies have liberated her from protracted housework, and a national education system occupies her children during their days. She is left to herself, consumed by nothing.

Both Friedan’s and Gustave Flaubert’s women have passing, rather than compelling, interests. They experience a crisis of purpose unfulfilled in domestic life.

Motherhood brings no meaning for Emma; her nature is so transformed by romanticism that she is incapable of transcendent joy. Friedan’s females too are disconnected from their children, and their disquiet grows with their children’s self-reliance.

Modernity and romanticism are common causes of these female feelings. Friedan’s housewife and Flaubert’s Emma are women of comfort and leisure; they are of the middle and genteel class, educated and financially secure enough to escape the necessity of work.

But abundant leisure and comfort often leads to dissatisfaction. Retirees are twice as likely to feel depressed as those working. And money does not buy happiness after one’s needs are met. Modernity sometimes doles out emptiness in exchange for material luxury.

Romanticism and imagination also prey on the languid. Emma reads too many sensational novels, cheap stories that entertain rather than offer an education in ethics (like Jane Austen). She becomes a consumerist, spending beyond her means in a hollow attempt to fill her emptiness with things.

The 1950s in America also offered such distractions. In 1949 to 1950, American households were already watching about 4.5 hours of television per day. Television’s longest-running soap opera premiered in 1952. And 75% of all consumer advertising budgets were spent on appealing to women.

Women of this era, like Emma, could lose themselves in the promises and bombardments of television, style magazines, and consumerism. Their imaginations could craft comparisons and illusions that left them disappointed with and disconnected from reality.

Though not mentioned by Friedan, another reason for the boredom of American women of this era was the decline of civic associations and private philanthropy, a political sphere significantly shaped by women in the past. For the social tradition of married women not having jobs in early America had led to extensive female voluntarism.

As Marvin Olasky describes, “During the 1820s, groups such as the United Female Benevolent Society of North Carolina (Fayetteville), the Female Benevolent Society (Newbern, N.C.), the Female Benevolent Society (Raleigh), and the Female Charitable Society (St. Louis) emerged … By the 1830s so much of this kind of activity was going on that American Christendom was said to be promoting a ‘Benevolent Empire.’”

Such projects gave women a sense of Christian purpose (a value that eludes Emma’s dabbling). Many of these programs were deliberately designed to equip citizens for self-government, teaching them the skills and discipline to move them toward independence.

Though the vast majority of women were not able to vote during this time, civic responsibility in America extends beyond the ballot box. Through civic associations, early American women were not only directing their children but also their fellow citizens in the art of self-government, participating in and perpetuating the highest promise of republican politics.

The first several decades of the 1900s marked a shift in philanthropy in America. Government programs began to emerge, professionals (rather than volunteers) worked in charities, and the well-to-do resided in communities separate from those receiving their assistance. All this displaced philanthropy and volunteering, for “initially the willingness to given money grew as the desire to give time decreased.”

The philosophy behind philanthropy also changed; it started becoming about material, rather than spiritual and civic, needs and virtues. It was less substantive and so provided less of a sense of purpose for those engaging in it. An avenue for women’s religious and civic contribution was blocked through the diminishment of civic associations.

Bereft of such meaningful engagement, well-to-do women organized endless activities for themselves, according to Friedan. One of her case studies notes, “I’ve tried everything women are supposed to do—hobbies, gardening, pickling, canning, being very social with my neighbors, joining committees, running PTA teas.”

This portrait is of an individual aimlessly filling hours with distractions and engaging in highly intensive parenting. It is a striking contrast to Olasky’s dynamic description of the higher service and citizenship of an earlier era.

Friedan attributed women’s unrest primarily to their roles as housewives and the monotony of housework, and thus her alternative was for women to pursue careers. She commonly cloaked such careers in romanticism and the American lure of high achievement: Women could split atoms, penetrate outer space, create art that illuminates human destiny, and be pioneers on the frontiers of society.

These are not women who have to pick up shifts at a hospital or restaurant to make ends meet (often a more realistic image of work). Friedan’s feminists are the elites whose comforts, like Emma’s, are ensured by their husbands.

They can evade the harshness that often accompanies work when it is a necessity. Flaubert used the tragic outcome of Emma’s romantic delusions (Emma herself commits suicide) to sear the need for realism in the reader’s mind; Friedan entices her readers with select illustrations.

There are reasons to distrust both the accuracy of Friedan’s analysis as well as her motivations. Her account of domestic life is bracingly critical, but some polls run counter to her conclusions, and she misrepresented others.

Consider as an alternative Austen, who shows family life to be intriguing, dynamic, and filled with everyday episodes of excellence and elegance. Austen is devoid of illusion, so her depictions, though the work of fiction, seem authentic.

Friedan’s work has been read by countless women, but how much did it resonate due to her feminist arguments versus her account of the sterile emptiness of American life in the 1950s?

Had something gone wrong in society and the hearts of these women for deeper reasons? Did women then have faith in her solutions because her descriptions hit home? At what cost?

In hindsight, it appears that the price of indulging in Friedan’s romance has been paid by more than her target audience. Now, the unrest, selfishness, consumerism, and crisis of purpose Friedan detailed has spread to American men (partly because of some of the changes the sexual revolution precipitated) and indeed throughout the West.

In 2014, life expectancy in the United States began declining, largely due to deaths from “drug and alcohol poisonings, suicide, and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis.” The birth rate has plummeted.

It is now more common for men and women alike to share in the tragedies depicted by Flaubert. Many modern individuals, like Emma, are no longer capable of finding purpose or fulfillment in having children.

For why would people wish to have children when we are killing ourselves? Though Flaubert’s work was written before Friedan’s, her romanticism proves the prescience of his realism about the future of the West.

This piece was originally published at Law & Liberty.

The Daily Signal publishes a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Heritage Foundation.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.