It took rioters only two nights to move through Kenosha, Wisconsin, burning and looting businesses as they went, until parts of the city looked more like a war zone than an American town.

“It’s emotional for us,” Raquel Santiago told The Daily Signal during an Oct. 7 interview, adding: “I don’t even have words to describe what my family [is] going through.”

An estimated 50 or more Kenosha businesses were affected by the riots that followed the Aug. 23 police shooting of a man who didn’t heed officers’ directions, Heather Wessling, vice president of the Kenosha Area Business Alliance, told The Daily Signal in an Oct. 8 interview.

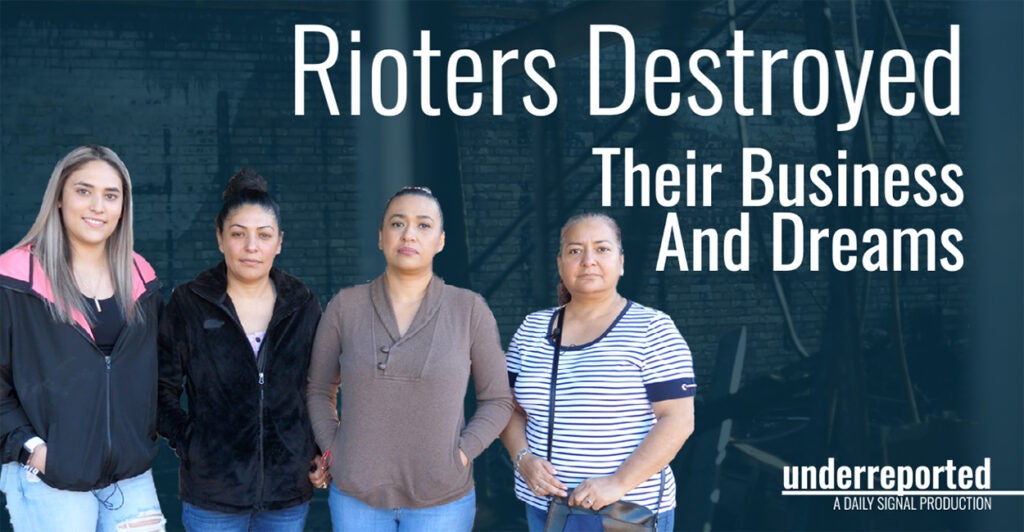

Several weeks after the riots, The Daily Signal traveled to Kenosha to speak with some of the affected business owners.

In a hotel room in downtown Kenosha, with Lake Michigan at their backs, Santiago and her sister Ruth Serrato recounted the night that vandals burned their family business to the ground.

“When you see that your job, all you [have been] working for [for] years, not just you, [but also] your parents and the future, probably of your kids, burning down for something you have nothing to do [with]. … This is just shocking,” Santiago said.

Santiago emigrated to America from Mexico in 1995. Her father, Miguel Anguiano Hernandez, traveled between Mexico and America from the time he was a teenager in the 1950s until he was able to permanently settle his family in Kenosha several decades later.

Sixteen years ago, Hernandez opened The Good Taste Ice Cream Shoppe there at 6122 22nd Ave.

The ice cream shop was a family endeavor with Hernandez’s wife, Aurora Anguiano, with Santiago and nearly all of 10 other children helping in some way.

“Everyone [had] a role,” Santiago said.

The family’s ice cream shop opened in the Uptown section of Kenosha, an area some in the community say is not safe, Serrato said. But in 16 years of business, she said, the family “never had like a window broke or something like that. Never.”

The peace Serrato and her family experienced for so many years ended abruptly Aug. 24, when rioters flooded Kenosha’s streets for the second night after the police shooting of Jacob Blake, 29, who is black.

A little before midnight Aug. 24, Serrato recalled, she saw in the shop’s camera that the family business was in danger.

“We go in right away and we can do nothing,” Serrato said.

The sisters stood and watched far into the morning of Aug. 25 as their business burned to the ground, “just like a nightmare,” Santiago said.

“You couldn’t even be close because the fire was too big,” she said, adding:

[It was] catching building to other building, you only can hope firefighters can stop it. They work so hard, they do the best they can. They are so great people, who try to help. But what can I say, this buildings are next to each other, shoulder to shoulder, and fire was so intense, so hot.

Several days after the fire, the sisters went down to their burned-out ice cream business, thinking that maybe something survived or could be salvaged. But nothing was left.

“Everything burned to the ground,” Santiago said. “Expensive machines, compressors. I mean, things that you cannot even think they’re going to burn because it’s metal. … It’s just garbage.”

Hernandez, Santiago and Serrato’s father, had spent years growing the family business. He “took a great portion of his retirement savings [to purchase] the equipment that that business would need to start an ice cream shop,” Kenosha Area Business Alliance’s Wessling said.

The loss of the business is proving to be especially emotional for the family because Hernandez died last year at the age of 80.

Hernandez and his wife ran a small popsicle business in Mexico before permanently emigrating to America. They dreamed about one day settling in the United States and opening their own business. The Good Taste Ice Cream Shoppe was the fulfillment of years of hard work.

Now, so much of what Hernandez worked for and left for his children and grandchildren is gone.

“This is emotional because [it] is his work, all he was dreaming for,” Santiago said, through tears. “All he was teaching us to do, something good for the family.”

In the wake of Hernandez’s death, the insurance for the shop’s equipment fell through the cracks. The building was covered, but the years of capital the family invested in freezers, compressors, and other machinery needed to make the ice cream is gone.

Despite the terrible loss, the sisters said they remain optimistic that they will be able to resurrect their father’s legacy.

“We think we are rebuilding again, not really now but as soon as possible,” Serrato said.

Organizations such as the Kenosha Area Business Alliance are stepping up to help The Good Taste Ice Cream Shoppe and other businesses destroyed by the riots.

Kenosha is a small town, Wessling said, so “we know the businesses that were affected and we know what their needs are.”

“We can likewise turn around the funds that are needed to rebuild and make sure that the businesses that were affected have access to those dollars,” she said.

When they are able to rebuild, Santiago said, the business will be even stronger because “when you lose something, you appreciate what you have.”

For Santiago, Serrato, and their whole family, hope in the American dream is still alive.

“Definitely America … is changing, but I believe for hardworking people, the dream [is] always going to be there,” Santiago said, adding:

All you have to do is work, work hard to get your dream, and you will get it because we are the example. My father work, he and my mom, they worked and saved. And with hard work, you can get whatever you want.