In the much-anticipated case of June Medical Services v. Russo, a divided Supreme Court on Monday narrowly struck down a Louisiana law that would have required abortion providers to submit to the same types of supervision and requirements as other, similarly situated physicians.

Once again, the court carved out special constitutional exemptions in the field of abortion law that don’t exist for anyone else.

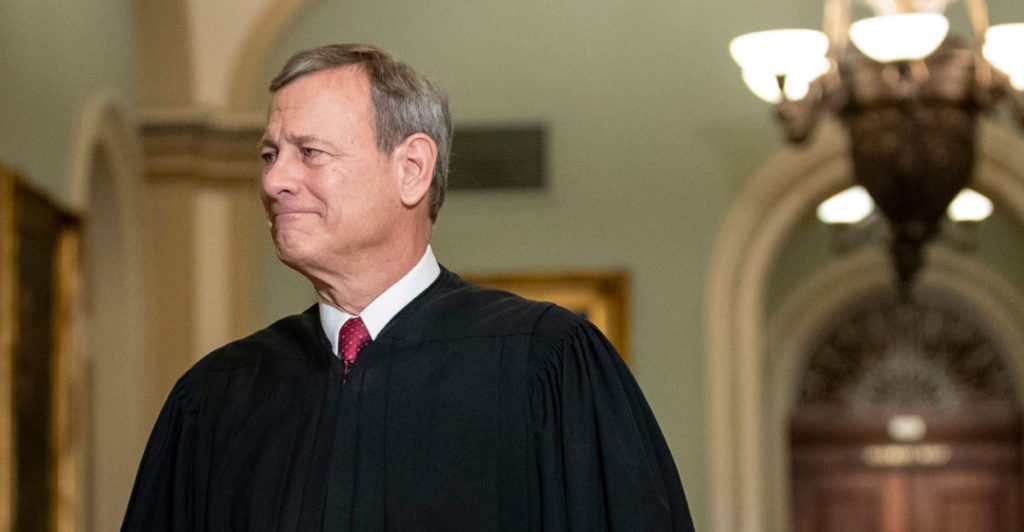

And once again, Chief Justice John Roberts provided a deciding vote for the court’s liberal wing, based on highly questionable reasoning.

What Was the Case About?

At its core, June Medical Services v. Russo was not a challenge to Roe v. Wade or a woman’s “right” to an abortion. The Louisiana law at issue neither outlawed abortion, nor imposed additional requirements directly on women seeking an abortion.

Instead, Louisiana passed a law requiring doctors who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital so that, if something went wrong requiring that the woman be hospitalized, the doctor could accompany her and treat here there.

The law was passed to protect the health and safety of women seeking abortions by acting as a quality-control measure for abortion clinics. That was not without good reason: The state’s abortion clinics have a long and well-documented history of hiring unqualified doctors who provided substandard care to patients.

The requirement of hospital admitting privileges is common for physicians who conduct surgical procedures elsewhere, and the process of obtaining such privileges provides additional oversight for those clinics.

Various abortion providers sued Louisiana to challenge the law’s constitutionality, arguing that it imposed an “undue burden” on their patients’ rights to obtain an abortion. They maintained that the law was nearly identical to a Texas statute struck down by the court in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016).

While the U.S. District Court initially held that the law was unconstitutional because it imposed an undue burden without any real benefit to patient health and safety, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit overruled the decision as “clearly erroneous” based on the robust record to the contrary.

The Liberals and Roberts Strike Down Law

In a narrow 5-4 majority comprising the court’s liberal justices plus Chief Justice John Roberts, the court reversed the 5th Circuit’s ruling and effectively struck down the Louisiana law as unconstitutional.

In an opinion by Justice Stephen Breyer, the four liberal justices determined that Whole Woman’s Health controlled as precedent, and that the Louisiana law was unconstitutional because it created an undue burden on women seeking abortions.

The court’s liberal wing reasoned that the 5th Circuit should not have questioned the district court’s factual findings or its conclusions that the law would “drastically reduce the number and geographic distribution of abortion providers,” making it “impossible” for many women to obtain an abortion.

Breyer wrote that the district court’s findings were not “clearly erroneous” and therefore should have been respected by the 5th Circuit.

Roberts did not join in Breyer’s opinion, but still concurred in the judgment—in other words, he agreed to strike down the law.

Roberts wrote that even though he believes Whole Woman’s Health was wrongly decided, he would nevertheless adhere to it under principles of stare decisis. He felt compelled to apply Whole Woman’s Health in this case, and gave the liberal wing its much-needed fifth vote by reasoning that this case was necessarily controlled by precedent.

Stinging Dissents

Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh wrote dissenting opinions.

Alito, Kavanaugh, and Thomas began their respective dissents by insisting that the court should not have heard this case in the first place, because the abortion clinics did not have proper standing to challenge the law.

In order to bring a case to court, parties must have proper “standing”—meaning they must demonstrate that they have suffered or will suffer as a result of the law.

But in this case, the parties challenging the law were not women seeking abortions, but abortion providers challenging the law on behalf of hypothetical patients who might seek abortions in the future.

Had the court treated the abortion providers under the same legal rules as other “third-party litigants,” it would have rejected the challenge altogether. But instead, the majority allowed special privileges to abortion providers.

With respect to the merits, the dissenting justices would not have struck down the law as unconstitutional for a variety of reasons.

As Alito astutely pointed out, “While it is certainly true that the Texas and Louisiana statutes are largely the same, the two cases are not.”

Whole Woman’s Health relied on an empirical question of the effect the law had on abortion access in that particular state, taking into consideration many factors—such as demand for abortion, the number of abortion clinics, and the ability of physicians to obtain admitting privileges—that clearly vary from state to state.

Just because the laws are similar does not, by itself, mean the effects of the law are the same in different states. For that reason, it was wrong to hold that the Louisiana law is unconstitutional just because the court earlier held the Texas law was unconstitutional.

Moving on to the question of whether the district court was “clearly erroneous” in holding that the law unduly burdened women and failed to meaningfully accomplish the stated goal of protecting patient health, the dissenting justices offered blistering criticisms.

Alito and Gorsuch in particular detail from the record precisely why the district court was clearly erroneous in holding that the law did nothing to protect women’s health and safety.

As Alito noted, Louisiana passed its law in the aftermath of the Kermit Gosnell grand jury report, which concluded that closer supervision—such as that required to obtain hospital admitting privileges—would have uncovered his egregious health and safety violations.

Consider also Gorsuch’s words:

Unsurprisingly, [the risks from abortion] are minimized when the physician providing the abortion is competent.

Yet, unlike hospitals which undertake rigorous credentialing processes, Louisiana’s abortion clinics historically have done little to ensure provider competence. … Clinics have even hired physicians whose specialties were unrelated to abortion—including a radiologist and ophthalmologist.

Requiring hospital admitting privileges, witnesses testified, would help ensure that clinics hire competent professionals and provide a mechanism for ongoing peer review of physician proficiency.

Thomas, meanwhile, wrote his own dissent, in which he had the courage to say what none of the other dissenting justices would; namely, that the court created the right to abortion “out of whole cloth, without a shred of support from the Constitution’s text.”

In Thomas’ view, it’s irrelevant whether the law imposes an undue burden on women seeking an abortion. Rather, all of the court’s “abortion precedents are grievously wrong and should be overruled.”

Roberts Places Institution Over Consistency

The unfortunate reality is that Roberts once again put concerns about the court’s image ahead of the rule of law and consistent jurisprudence. He chose to abide by a four-year-old precedent that he contended—and still contends—was wrongly decided, instead of overturning that clearly incorrect decision.

Roberts’ choice is even more confusing, given that he has voted to overturn much more entrenched precedents. In recent years, he voted to overturn decades-old precedent in both Janus v. AFSCME and Knick v. Township of Scott. (In fact, he wrote the majority opinion in Knick.)

The current case provided just as many, if not more, reasons to refuse to abide by principles of stare decisis.

Meanwhile, if the chief justice had simply wanted to get rid of an uncomfortable case without ruling on the merits, he certainly had ample opportunity to do so by properly applying the third-party standing doctrine.

This would not have been the first time this term he would have avoided a contentious merits ruling through procedural technicalities, but at least in this case, it would have been sound jurisprudence.

Instead, Roberts once again gave the liberal wing of the court a fifth vote in a very politically divisive case, handing a victory to liberal policy preferences instead of to consistent jurisprudence.