Public health officials advising governments here and abroad on the COVID-19 pandemic so far have offered shifting and tentative guidance on when and how to unwind the practice of social distancing.

Asked recently when the U.S. could return to normal, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the chief medical adviser to the Trump administration’s coronavirus task force, suggested that it couldn’t occur until the public is “completely protected.”

“If back to normal means acting like there was never a coronavirus problem,” Fauci told CNN on April 9, “I don’t think that’s going to happen until we do have a situation where you can completely protect the population.”

>>> When can America reopen? The National Coronavirus Recovery Commission, a project of The Heritage Foundation, is gathering America’s top thinkers together to figure that out. Learn more here.

The standard of complete protection is at once noble and unattainable. Neither the U.S. nor any government ever has completely protected its citizens from contagion.

The Data

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that nearly 61 million Americans were infected in 2009, the last time a novel virus (in that case, H1N1) reached pandemic proportions.

The seasonal flu killed an average of 37,000 Americans a year between 2010 and 2019, according to the CDC, with 24,000 deaths so far in the current season. The 2017-18 flu strain was especially virulent, claiming 61,000 lives.

This last figure is similar to the number of deaths that the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, or IHME, was projecting to occur by August from COVID-19.

That projection, operative as of April 23, is provisional. The IHME forecasts change frequently and fluctuate wildly, and other computer models have produced a wide range of predictions about COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus.

COVID-19 hospitalizations, according to the CDC, “are highest among older adults, and nearly 90% of persons hospitalized have one or more underlying medical conditions.”

That profile is similar to the seasonal flu, where 92.3% of those hospitalized had at least one comorbidity—that is, another chronic disease or condition. Age and comorbidities thus are important indicators of whether COVID-19 will cause illness serious enough to require hospitalization.

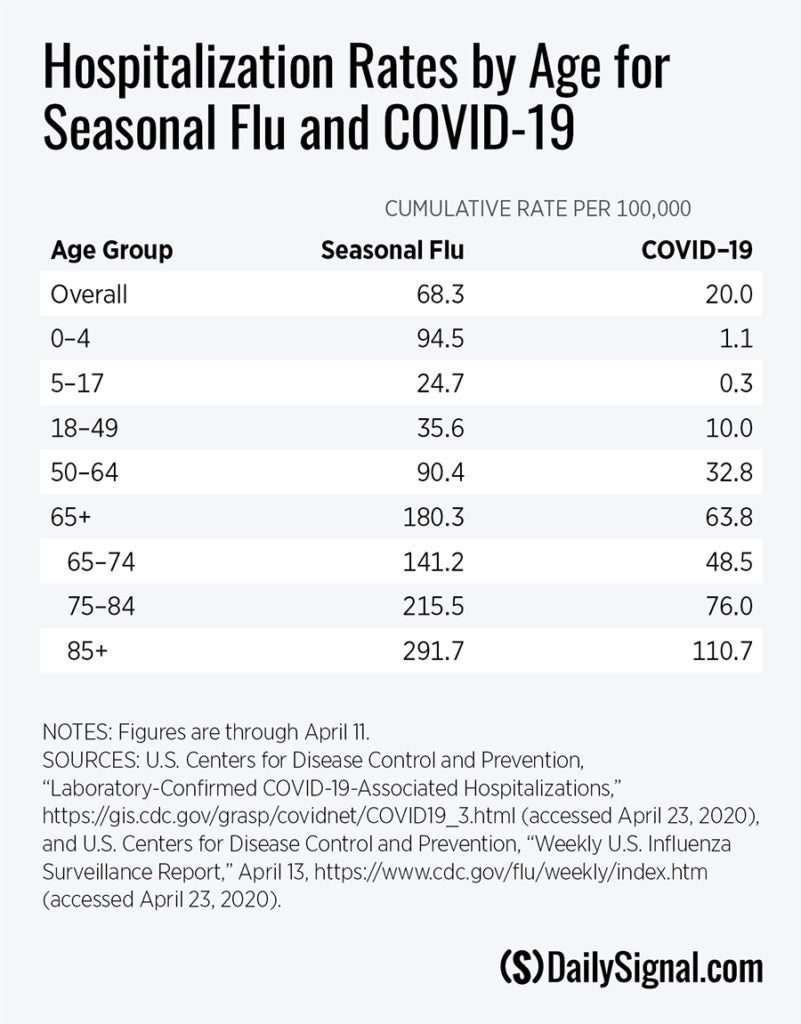

The table below shows that hospitalization rates for COVID-19 through April 11 are much lower in every age group than for the seasonal flu. This situation could change with time, but hospitalization rates essentially would have to more than triple in the aggregate to equal the rates of this year’s seasonal flu.

Disparities in hospitalization rates vary by age. For example, the rate for the seasonal flu for children aged 5-17 is more than 80 times as high as for COVID-19 (24.7 per 100,000 vs. 0.3 per 100,000).

The hospitalization rate per 100,000 for the seasonal flu also is much higher for those aged 18 to 49 (35.6 vs. 10 ) and those aged 50 to 64 (90.4 vs. 32.8).

The hospitalization rate for both COVID-19 and the seasonal flu are similarly highest for seniors. The highest hospitalization rates for both are among those aged 85 and older. The COVID-19 hospitalization rate for this group is more than five times the overall rate and well over 300 times as high as for the school-age population.

And yet, although most jurisdictions have closed schools, few have taken the steps necessary to protect the elderly, particularly those in nursing homes.

That is not to equate COVID-19 with the seasonal flu. It is caused by a novel coronavirus for which there is neither a cure nor a vaccine. Its transmissibility, lethality, and prevalence remain unknown.

The comparison does show, however, that perfection in the battle against infectious diseases is not a reasonable, or even attainable, goal.

Tragically, tens of thousands still die from the seasonal flu because it is impossible to completely protect the population—from influenza, COVID-19, or any other natural disaster. It would be foolish to ignore the measures that can protect us, but it also is unrealistic to think that we can protect everyone from getting sick.

Yet, that is the standard that Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, seemed to suggest must be met for the U.S. to return to normal. And this standard points to a problem with the policy of social distancing that goes beyond the economic carnage it is exacting in most highly developed countries: It’s never clear when it’s safe to return to normal.

The internal logic of social distancing dictates that, so long as those who are infected circulate in the community, everyone must treat everyone else as a carrier. And so long as there are carriers, returning to normal risks a “second wave” of contagion.

As many public officials have acknowledged, social distancing “flattens the curve” of infection but also elongates it. Instead of a high and rapid spike in infection followed by an abrupt decline, social distancing causes the wave of infection to rise more slowly, peak at a lower level, and trace a long downward slope. And once people do start back to work, a new wave of infections can crest.

Social distancing, in other words, doesn’t end the pandemic. Individuals continue to get infected, absent an outside event such as a cure, a vaccine, or a seasonality that slows the spread of the virus once the weather heats up.

Thus it is nearly impossible to develop objective dates for ending social distancing.

Fauci recently told reporters that government officials can start to “think about a gradual reentry of some sort of normality, some rolling reentry,” only after the number of people who are seriously ill sharply declines. That is the approach taken in the Trump administration’s guidelines for “Opening Up America Again.”

A Different Approach

Getting back to normal can begin now in some places. That is because the pandemic has not been evenly spread across the states or even within states.

Various regions of the country have very different case numbers and hospitalizations.

For instance, the New York City area, where more than 8 million live, has seen nearly 36,000 hospitalized with the virus (0.45%). In Louisiana, another hot spot, 2,000 have been hospitalized and more than half of the cases are in the New Orleans metropolitan area, home to 1.3 million.

In contrast, between Maryland and Virginia, a bit more than 3,000 COVID-19 patients have been hospitalized. Combined, these two states are home to 14.5 million, so the portion of seriously ill in this region because of COVID-19 is around 0.02%.

Many other areas of the nation have fewer cases and hospitalizations. Three-fourths of all counties in the U.S. have no more than 50 cases, half of all counties have 10 or fewer cases, and almost 40% have five or fewer.

However the unwinding of social distancing proceeds, public health officials will face challenges. They have convinced the vast majority of Americans to sharply curtail social interactions to avoid getting sick.

Health officials now will have to convince Americans to return to “some sort of normality,” even though the infection continues to spread.

Officials will have to reassure us that because fewer are dying in May or June than in March or April, we can engage in activities that these same officials only recently pronounced unsafe.

That will be a challenge, rendered more formidable by the inherently open-ended nature of social distancing. But convincing Americans to return to work and play when a risk of contagion remains is much easier than aiming to “completely protect the population.”