$1.8 trillion.

That’s the official price tag on the federal government’s most recent stimulus bill, passed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

That estimate is lower than previous projections of $2.3 trillion, in part because it excludes loan guarantees on debt that the government expects will be repaid.

How much is $1.8 trillion in the scope of federal spending?

>>> When can America reopen? The National Coronavirus Recovery Commission, a project of The Heritage Foundation, is gathering America’s top thinkers together to figure that out. Learn more here.

U.S. officials at all levels of government have taken exceptional actions to contain the spread of COVID-19, a disease caused by a novel coronavirus that originated in Wuhan, China.

Since the imposition of social distancing requirements, travel restrictions, and widespread stay-at-home and economic shutdown orders, almost 22 million Americans have filed for unemployment compensation, while some businesses have closed their doors permanently.

The Trump administration and Congress have enacted three separate coronavirus relief packages at a total cost of more than $2 trillion.

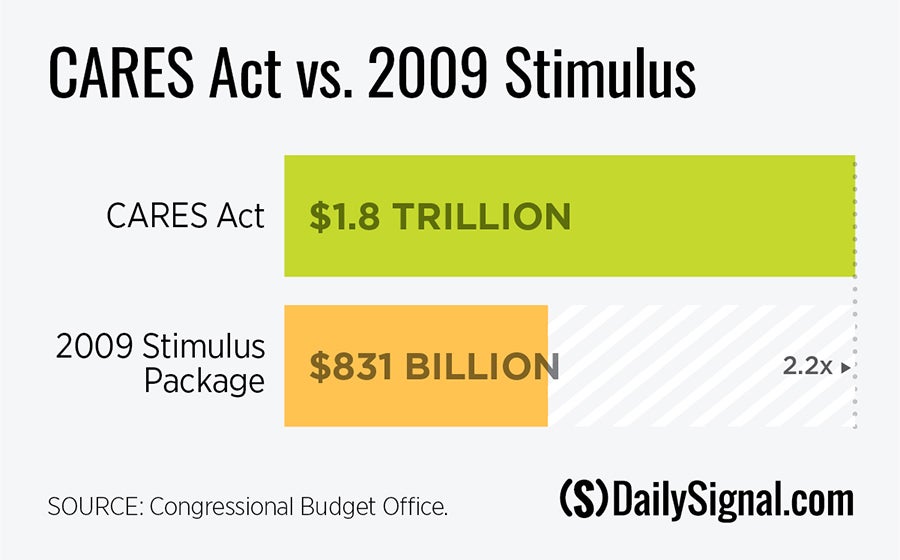

The most recent legislation—the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act—provides $1.8 trillion in direct aid to individuals and businesses, the largest stimulus package in U.S. history.

While $1.8 trillion is a huge sum of money, how does it rank in the context of other federal spending?

In 2009, the U.S. found itself amid what at that time was its largest economic contraction in 80 years. During the Great Recession, America’s unemployment rate rose to 10%, and at one point, the stock market had lost nearly 50% of its value.

In response, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which injected $831 billion into the U.S. economy through tax cuts and spending programs.

The CARES Act, which passed in March, is more than twice the size of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, dwarfing what was previously the country’s largest stimulus package since World War II.

To put the scope of the CARES Act into further perspective, consider the federal government’s discretionary budget. The discretionary budget consists of most federal departments and programs that are not related to Social Security, health care, or income security programs.

In fiscal 2019, the federal government spent a total of $1.3 trillion on discretionary programs. That’s just over 74% of the spending approved in the CARES Act alone.

Of that $1.3 trillion, Congress allocated $676 billion for national defense. In the next two and a half years, current projections show the federal government spending less on national defense, in total, than it has authorized for coronavirus relief spending in the CARES Act.

Even relative to the size of the entire federal budget, the CARES Act is substantial.

In 2019, federal revenues totaled $3.5 trillion. The CARES package alone will consume more than half of those revenues.

Last year, the federal government spent nearly $1 trillion more than it took in. Before the coronavirus crisis, the Congressional Budget Office projected that trillion-dollar-plus deficits were here to stay for at least the next 10 years. The CARES Act will add $1.8 trillion more to the deficit in 2020 alone.

Once you add in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act at $192 billion and the initial Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act at $8 billion, the federal government deficit for 2020 has been tripled. The long-term debt impact, with additional borrowing costs included, would be even greater.

Where do we go from here? The federal government has an important role to play in keeping Americans safe in responding to a public health crisis. More than $2 trillion in total already has been spent on coronavirus response efforts with the possibility of hundreds of billions more likely to follow in the coming weeks.

To predict a crisis of the magnitude of the coronavirus is impossible. However, the federal government finds itself unprepared to respond to even relatively small natural disasters, let alone a global pandemic.

Congress and the administration were living it up with large-scale spending increases, such as the $300 billion Bipartisan Budget Act, even after Congress adopted tax cuts. Spending increases on top of tax cuts is the height of fiscal irresponsibility.

Once the immediate public health crisis abates, Congress must focus on reining in federal spending and focusing its priorities on programs that fall within the constitutional scope of the federal government.

Activities falling outside of that limited scope should be left to local governments and to the private sector, which are better at managing issues of local importance and in serving their customers and constituents’ needs.

President Donald Trump’s budget proposals would move the federal government in that direction, but bolder reforms are needed.

Lawmakers should ensure the nation is prepared to respond to national emergencies when they arise by living within sustainable means and by focusing federal resources and expertise where they are most needed. That will allow lawmakers greater flexibility to respond to crises, without significantly increasing the risk of a fiscal crisis.

The stakes are high, with the prosperity of current and future generations hanging in the balance.