Amid the drama surrounding impeachment, both parties came together on one area of shared support: spending enormous amounts of taxpayer dollars and adding to the $23.1 trillion national debt.

Congress had little time to properly review fiscal 2020 spending bills, which weighed in at more than 2,000 pages of clunky text.

The legislation contained a multitude of flaws, including lobbyist-driven handouts and a private-pension bailout that could open the door for even larger bailouts down the line.

This is a business-as-usual conclusion to an irresponsible decade. The degree to which Washington has been reckless with the nation’s finances is hard to comprehend.

Since 2010, the federal government has spent $293,750 per household.

Federal spending started the decade at an artificially high level due to the 2009 “economic-stimulus” package. There was a slight dip after the stimulus ended, and the tea party wave ushered in a brief period of restraint in Congress. Sadly, this flicker of responsibility was short-lived.

According to the Office of Management and Budget and the Congressional Budget Office, federal spending totaled $37.6 trillion from 2010 through 2019. Spread across 128 million households (per the Census Bureau), that yields $293,750 in spending for every household.

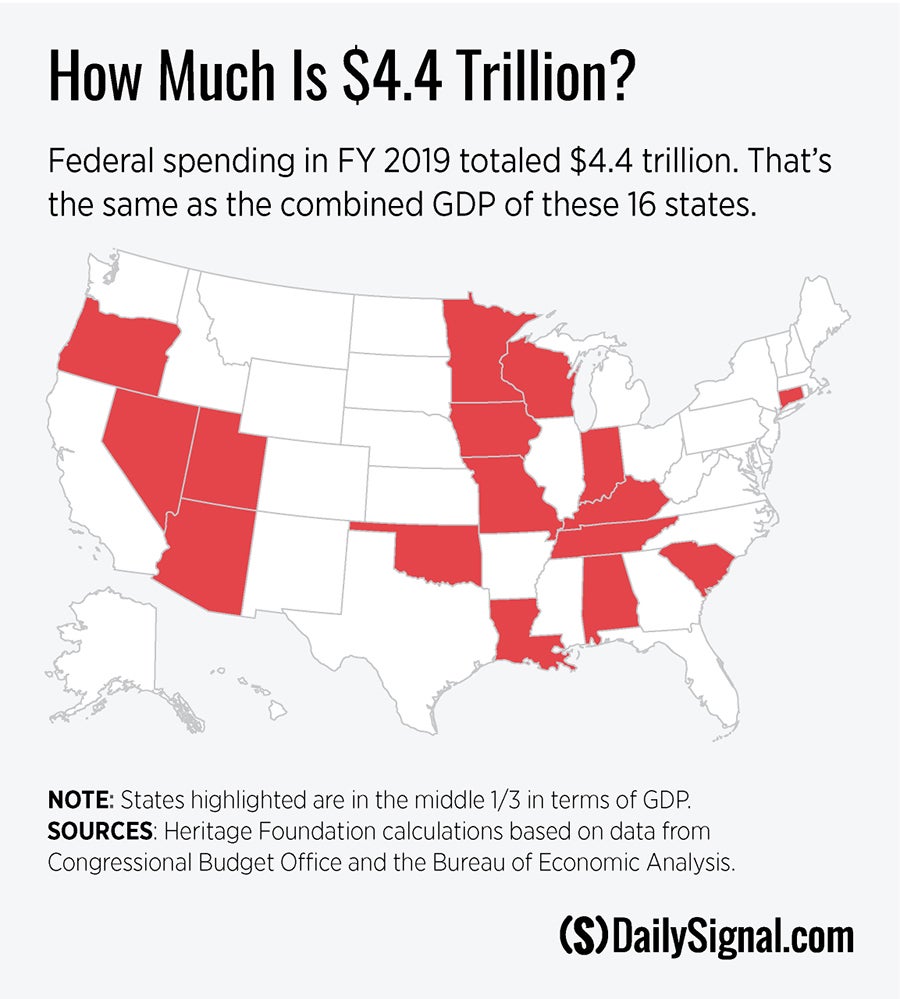

Federal spending in 2019 was equivalent to the combined economies of 16 states.

In fiscal 2019, which ended Sept. 30, the federal government doled out $4.4 trillion. The full scope of that much money is virtually impossible for the human mind to grasp. One way to understand the sheer enormity is by comparing it to the size of state economies.

To match the amount that the federal government spent in fiscal 2019, one would need to add the total economic output of Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, and Wisconsin.

We should treat the notion that this level of federal activity is too small with deep skepticism.

Spending per household is up 47% since 2000.

The federal government spent $34,700 per household in 2019, which is serious money no matter what part of the country you live in.

Is nearly $35,000 per household too much spending? To put it in context, we can go back to the last time the economy had a surging stock market and unemployment under 4%, the year 2000.

Back then, federal spending was about $2.49 trillion after adjusting for inflation. Divided by the number of households in 2000, the government spent just $23,600 per household in today’s dollars.

That means that the spending increase from 2000 to now is a staggering 47% per household, even after controlling for inflation. In real terms, the federal government is nearly half-again larger than it was less than two decades ago.

The budget would balance today if spending had grown more modestly.

With the federal government growing so quickly, it should come as no surprise that this year’s deficit likely will exceed $1 trillion, even if the economy remains strong.

Some on the left counter that the high deficits are primarily the fault of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, signed into law just before Christmas 2017, and that the solution is funneling more taxpayer dollars to Washington. That assertion is incorrect.

Once again, a comparison to 2000 is instructive. Revenue per household, adjusted for inflation, was $26,750 in 2000. Today, it’s roughly $27,000, even after the 2017 tax cut.

If federal spending had grown based only on population and inflation starting in 2000, today’s trillion-dollar deficit would turn into a surplus.

Policymakers should recognize that the federal government has grown far too quickly. Since there is no way to undo the past, they should take some prudent steps to return the country to sound financial footing.

First, Congress should trim excessive spending that has accumulated over the years. The Heritage Foundation’s Blueprint for Balance offers hundreds of policy ideas to save money by eliminating waste, making Social Security and Medicare sustainable, and slashing perks for politically connected industries.

Second, Congress should enact meaningful guardrails that rein in future spending growth. One model for reform comes from Switzerland, where the budget balances over the course of a business cycle.

Closer to home, the “taxpayer bill of rights” approved by Colorado voters in 1992 limits spending based on a combination of revenue, inflation, and population growth.

Such rules would create headaches for Washington by forcing big-spending members of Congress to make tough decisions, rather than all of them getting what they want by abusing the national credit card.

Yet this would merely force legislators to behave the way most families do every day; namely, pay for necessities first, and only add extras if there’s cash to spare.

Congress is ending the decade on a note of fiscal irresponsibility, but next year lawmakers have a fresh chance to do right by America.