Shrinking the national debt would do a world of good for the country.

For one, it would allow us to ensure a strong national defense in the face of rising global threats. It would allow us to preserve and build on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act to keep taxes low and unleash further investment.

It would also boost incomes. A new analysis by the Congressional Budget Office found that shrinking the debt back down to its average historical level could boost incomes by $5,500 per person in 30 years.

But rather than seize that opportunity, Washington keeps adding to the debt.

The U.S. national debt just reached $22.3 trillion. When the debt limit was raised as part of the Mnuchin-Pelosi budget deal recently signed by President Donald Trump, the debt took a big jump to account for the Treasury’s borrowing via loopholes (“extraordinary measures”) since it was last bound by a debt limit.

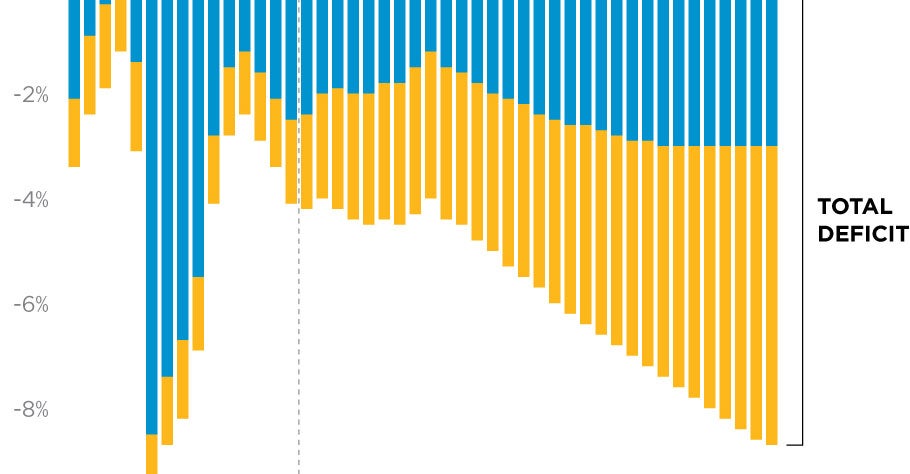

That Mnuchin-Pelosi deal will add $320 billion in new spending over the next two years, catapulting annual budget deficits well past the $1 trillion mark. Such wide deficits haven’t been seen since the years immediately following the Great Recession.

Worse than previous budget deals agreed on during President Barack Obama’s tenure, the deals cut under the Trump administration ignore the excessive and worsening spending problem the nation faces and neglect to take deficits and debt seriously by failing to offset new spending with spending cuts elsewhere.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that over the next 10 years, this latest budget deal will increase deficits by $1.7 trillion.

The problem with the government running high and rising yearly budget deficits is that they burden younger and future generations by consuming resources today instead of investing them, and adding to the national debt.

The debt also generates interest costs, which divert taxpayer money away from other national priorities toward paying the borrowing costs for spending that was done in the past.

At year-end (the fiscal year ends on Sept. 30), if the government spent more money than it collected in taxes, this results in a budget deficit. The deficit for that year adds to the total amount the government owes: the national debt.

The national debt incurs a cost, called interest. Just like the interest we pay on mortgages and car loans, the federal government owes interest on the national debt. And this interest cost is growing rapidly.

The debt itself is also vast and growing. Publicly held debt (over $16 trillion of the more than $22 trillion in national debt) is at 78% of gross domestic product and is expected to reach 100% within the next 10 years.

Right now, paying off the national debt would require $67,000 from every single person living in the United States. That’s more than $200,000 for a family of three. Add in debt owed to federal government agencies—intra-governmental debt—and the gross national debt already exceeds the U.S. economy, which was $20 trillion in total in 2018.

Why don’t people care?

When government debt is this high and continues to grow, it hurts economic prospects and reduces our nation’s prosperity, slowing economic growth, reducing incomes, and paving the way for a debt-driven financial crisis.

That would mean significant job losses, lower wages for those who can keep their job, and massive tax increases on the American people.

But most people seem to have a hard time pinning those bad outcomes on government overspending and debt. And so politicians in Washington keep increasing spending and deficits and getting away with it.

In the big picture, some of this comes down to politicians wanting votes, and getting votes for them means spending money to please constituents and maintaining and expanding government services.

According to the Constitution, Congress has the power of the purse. This means that lawmakers in the House and Senate have the duty of writing and passing a budget, and writing and passing spending bills to enact the budget.

The president also wields significant influence in this process by either signing or vetoing spending bills that are sent to him (or her) by the Congress. While the president’s primary function is to execute laws, he (or she) is influential in directing the budget based on the will of the country.

This term, the administration proposed big cuts to spending to try to address the deficit problem and reduce the size and scope of government, but lawmakers haven’t gotten on board.

The president’s budget has fallen on deaf ears in Congress. All the while, Congress failed in its most basic and core duty: to pass a budget in the first place.

An important question arises from this situation: If the president proposed to cut spending in his own budget, why did he sign the $320 billion budget deal?

It takes 60 votes in the Senate to pass a spending bill. The president likely supported this spending deal in order to reach agreement and avoid a government shutdown and automatic spending reductions to national defense, which were scheduled in law.

The deal also supports the president’s priorities to advance defense spending and fund important programs for veterans.

Nevertheless, it came at too high a price.

The deal also raised the debt ceiling. Worse, though, it did not limit the debt to a new ceiling but instead suspended the debt ceiling all together. This allows lawmakers to keep spending money they don’t have, without any limit, for the time period of the debt limit suspension.

That’s like giving Congress a credit card with no credit limit for two years—through August 2021.

Both Congress and the president need to come together and forge an agreement to stop out-of-control spending.

For that to happen, regular Americans need to realize what a big issue growing spending and the debt is and how it affects their ability to live safe and financially prosperous lives.

After all the political conflict we observe, lawmakers seem to be able to agree on one thing: spending more of taxpayers’ money, including money they haven’t agreed to give them. It’s critical that Americans realize that Washington’s spending addiction will come to bite us later.

Congress and the president have the responsibility to enact change, but we the people are ultimately responsible for demanding that change.