Let us pause to celebrate the 50th anniversary this Saturday of a mission once thought impossible: the landing of a man on the moon.

Let us proclaim, without embarrassment, that America, and only America, had the requisite leadership, scientific community, and resources to make it possible for Apollo astronaut Neil Armstrong to take that giant leap for mankind.

Let us freely admit we needed a kick to get started. That happened when the Soviet Union put the first satellite known as Sputnik in orbit and pushed ahead of the United States in the space race. The Cold War was red hot, and everything was measured on how it affected that global conflict.

As one commentator wrote, “the United States could not afford [a] slight to its technical expertise and economic strength.”

In a dramatic address in May 1961, President John F. Kennedy tasked NASA with the goal of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth,” and to do so before the end of the decade. The following year, Kennedy raised the stakes of the Apollo program by calling space “a new frontier” and declaring: “We choose to go to the moon, not because it is easy, but because [it is] hard.”

It was far beyond hard, requiring the skill and dedication of 32 astronauts, including Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee, who died in a tragic 1967 accident, $25 billion in federal funds—an estimated $115 billion in today’s dollars—and the everyday commitment of the 400,000 workers, military and civilian, of the space program.

Ironically, America got critical help from a German rocket scientist, Wernher von Braun, who designed the V-2 rockets that rained down on Britain during World War II.

Von Braun moved to the U.S. and became an American citizen. He and his American team built a U.S. rocket, the Saturn, capable of a lunar landing mission while the Soviets could not.

Russia’s Sputnik was a walk in the park compared to Apollo 11’s unprecedented lunar landing mission.

“I consider a trip to the moon and back,” said Michael Collins, the third member of the Apollo 11 crew, “to be a long and very fragile daisy chain of events.” Twenty-three critical things had to occur “perfectly,” recalled engineer JoAnn Morgan at the Kennedy Space Center.

From the beginning, the moon landing enjoyed bipartisan support in Congress although some members argued that the civilian space program might weaken support of the military budget.

When Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, immediately made the Apollo mission a priority and transformed it into a Kennedy memorial that captured the imagination of Americans.

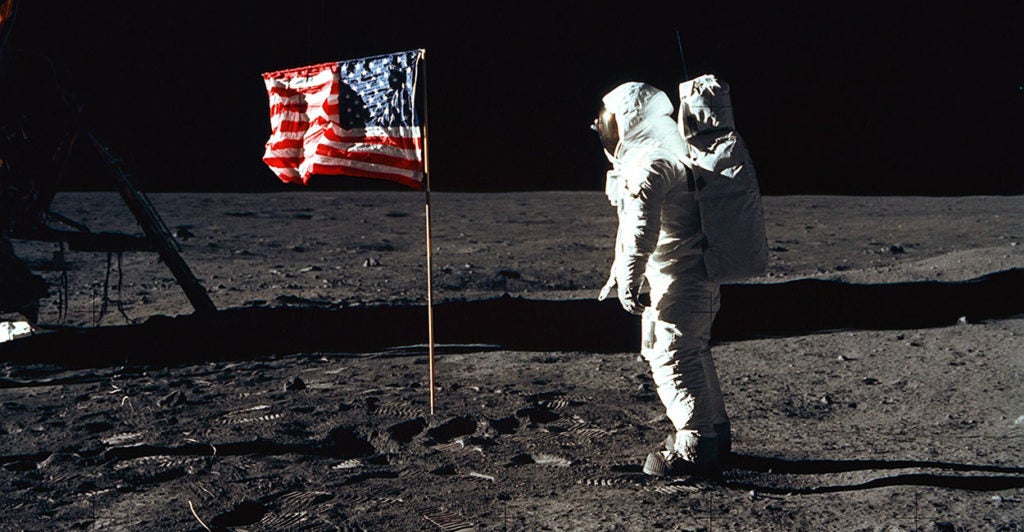

When Armstrong took his first step on the lunar surface on July 24, 1969—broadcast on live TV to a worldwide audience of an estimated 500 million people—he described it, memorably, as “one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

He had barely finished speaking and welcoming fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin to the surface when President Richard Nixon reached them by telephone from the White House.

Nixon emphasized the universal pride in the astronauts’ accomplishment: “For one priceless moment in the whole history of man,” he said, “all the people of this Earth are truly one: one in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to earth.”

The American people greeted the historic flight with an extraordinary outpouring of pride and patriotism. The 1960s had been a tragic decade, marked by the assassination of Kennedy, the murders of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert Kennedy, the quagmire known as the Vietnam War, racial riots, and mass anti-war demonstrations.

Now, at last, Americans had something to cheer about. Only an exceptional nation like America could have conceived, planned, and executed successfully the lunar landing and safe return of the three crew members of Apollo 11.

The post-landing celebration began at a California banquet hosted by Nixon and California Gov. Ronald Reagan, who recalled thinking that the men and women of NASA had changed forever “our concept of the universe.” Fifteen years later, President Reagan returned to that theme at a White House ceremony on the anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing.

“The Apollo program,” the president said, “was a noble achievement of the mind, the heart, and spirit—and the most ambitious and complex program ever undertaken in peacetime.”

Of the astronauts, he said, “How our astronauts with their quiet confidence, superb professionalism, and inner strength, lifted our feelings, our spirits, and our feeling of good will.”

He pointed out that the Apollo project had “spawned communications, weather, navigation, and Earth resource satellites, and many new industries like solid-state electronics, medical electronics, and computer sciences.”

Although Apollo was a project of peace, it had a profound effect on the Cold War. In 1970, a few months after the lunar landing, Soviet dissident and Nobel Laureate Andrei Sakharov wrote in an open letter to the Kremlin that America’s ability to put a man on the moon proved the superiority of a democracy.

That the Kremlin agreed with Sakharov can be seen by their ready acceptance of the Strategic Defense Initiative as something that the United States had the technical ability and economic wherewithal to launch.

In the words of the lunar geologist Paul Spudis, “Here is Apollo’s legacy. Any technological challenge American undertakes, it can accomplish.” That includes everyday things such as freeze-dried food, Velcro, scratch-resistant coatings on eye glasses, and the insoles that make sneakers comfortable.

The Apollo astronauts went where no one had gone before and did what no one had done before, changing forever, as Reagan said, our concept of the universe.

Is a man on Mars the next leap? Why not? After all, we are Americans.