Recent events in higher education have led many to conclude that college campuses are hubs of anti-Semitism.

Stanford University student and resident assistant Hamzeh Daoud declared in July 2018 his intent to “physically fight Zionists on campus.” Oberlin College professor Joy Karega asserted in November 2016 that U.S. intelligence agencies conspired with Israel to commit the Charlie Hebdo massacre. In April 2018, professor Kwame Zulu Shabazz of Knox College tweeted that Jews are “pulling the strings for profit.”

Stories like these make Victor Davis Hanson’s observation that “colleges are becoming the incubators of progressive hatred of Jews” ring true. Higher education is helping to make anti-Semitism respectable again.

Most coverage of anti-Semitism on campus has focused on leftist and pro-Palestinian student groups such as the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement.

Yet, as National Association of Scholars President Peter W. Wood and I discovered while researching “neo-Segregation” in higher education, campus anti-Semitism also stems from “woke” black activism.

“Woke” politics is a radical ideology with roots in a strain of black nationalism that rejected the civil rights movement’s goal to promote racial integration throughout American society.

To be woke means to become “radically aware and justifiably paranoid,” convinced that insidious actors and institutions contrive to keep black America down.

It means believing that whites participate in “structural racism,” which is both seen and unseen, and which bears the blame for blacks’ falling test scores, scant presence in elite colleges, and overrepresentation in America’s inmate population.

Wokeness’ paranoia of whites is epistemically structured similarly to Jew hatred, priming black nationalists to articulate anti-Semitism as they would anti-whiteness.

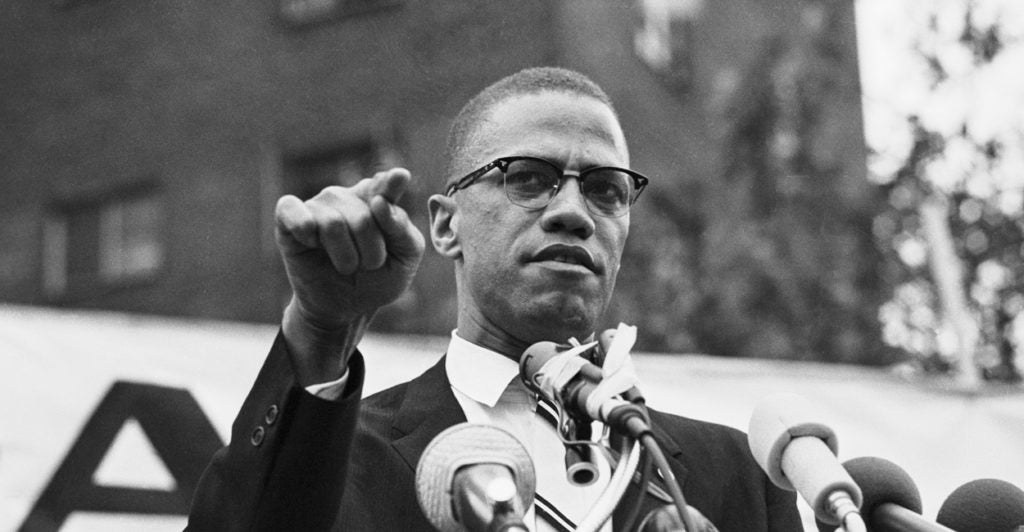

Malcolm X’s autobiography, which described his conversion to the Nation of Islam, was especially effective in spreading anti-Semitism.

“Look at practically everything the black is trying to integrate,” Malcolm X wrote, “if Jews are not the actual owners, or are not in controlling positions, then they have major stockholdings [sic] or they are otherwise in powerful leverage positions.” Asked Malcolm X, do Jews “sincerely exert these influences?”

Malcolm X believed in “Yacub’s History,” the foundational myth of the Nation of Islam, which teaches that whites and Jews were created 6,000 years ago by Yacub, an evil scientist.

Malcolm X said that the whites created by Yacub dwelled in caves until “Allah raised up Moses to civilize them.” He added that “the first of these devils to accept [Moses’] teachings … were those we call today the Jews.”

Yale University invited Malcolm X to address students in 1962. It soon became fashionable for other colleges to host black nationalists that espoused similar ideas, reinforcing just how out of touch higher education was and is from mainstream America.

In 1979, the Africana Studies Department at the State University of New York, Stony Brook hired poet Amiri Baraka as a lecturer. It didn’t mind that he had once written that he desired to murder Jews en masse.

In his book, “Black Magic: Poetry, Sabotage, Target Study, Black Art, 1961-1967” (1969), Baraka wrote:

Smile, Jew. Dance, Jew. Tell me you love me, Jew. I got something for you now though. I got something for you, like you dig, I got. I got this thing, goes pulsating through black everything universal meaning. I got the extermination blues, jewboys. I got the Hitler syndrome figured.

The school promoted Baraka to a full professor in 1985.

Black students at Yale University took up the mantle of anti-Semitism in the 1980s, a decade when Jew hatred emerged as a strident theme in mainstream black politics.

Speaking at Calhoun College in 1985, Millard Owens ’87 of the Black Student Alliance at Yale declared that Jews and blacks had been set at odds.

He vowed that tensions would persist, citing that blacks often encountered four kinds of whites: policemen, landlords, store owners, and social workers.

“Aside from the policeman,” he said, “the remaining three were usually Jews who sparked tension when prices rose.”

The Black Student Alliance at Yale neither condemned nor distanced itself from Owen’s remarks.

Yale indulged anti-Semitism again in February 1990 when students from the Journal of Law and Liberation invited Abdul Alim Muhammad, a Nation of Islam deputy, to speak on campus.

Muhammad was scheduled to discuss the war on drugs, but he instead used the event to allege that “Jewish doctors [injected] blacks with the AIDS virus.”

Muhammad’s speech inspired the Black Student Alliance to invite Louis Farrakhan to speak that March. Farrakhan’s speakership never materialized, but his invitation showed the Black Student Alliance’s readiness to “platform” a speaker that promoted hate.

In February 2003, the alliance invited Hitler-Syndrome poet Baraka to speak at Yale’s African American Cultural Center. Assistant Dean and Director of the African American Cultural Center Pamela George defended his appearance, insisting that it highlighted the importance of “free speech as a fundamental tenet of the university.”

Baraka had also participated in several Yale events, including an academic conference. Said George, Baraka was “not new to Yale.”

Campus black nationalists’ affinity for anti-Semitic tropes emerged again in April 2019 when a black “student leader” at the University of California, Berkeley said at a student meeting that “the [Israel Defense Forces] trains the police departments in America to kill black people.”

The liberation of blacks and Palestinians, she claimed, were “intertwined” because Zionists support the “prison industrial complex,” “prison militarization,” and “modern-day slavery.”

These stories testify to the toxicity of anti-Semitism, reminding us that even among American blacks, a group once allied with Jews in the struggle for civil rights, it can manifest behind a veil of “woke politics” and “diversity.”

Each story shares a common thread: Race-nationalist demagogues poured contempt on Jews and depicted them as a hidden force guiding human events to the misfortune of others.

Each occurred at colleges that have a duty to nourish in students dispassionate reasoning, intellectual seriousness, and a desire to pursue truth.

Higher education is increasingly showing its inability to live up to that task.