John Marshall may not have a Broadway play about his life, but the Founding Father deserves recognition from Americans as one of the chief architects of our system of government.

A new book by Richard Brookhiser, a senior editor at National Review and an esteemed historian, presents an interesting character study of one of the greatest—if somewhat unheralded—men in the history of our republic.

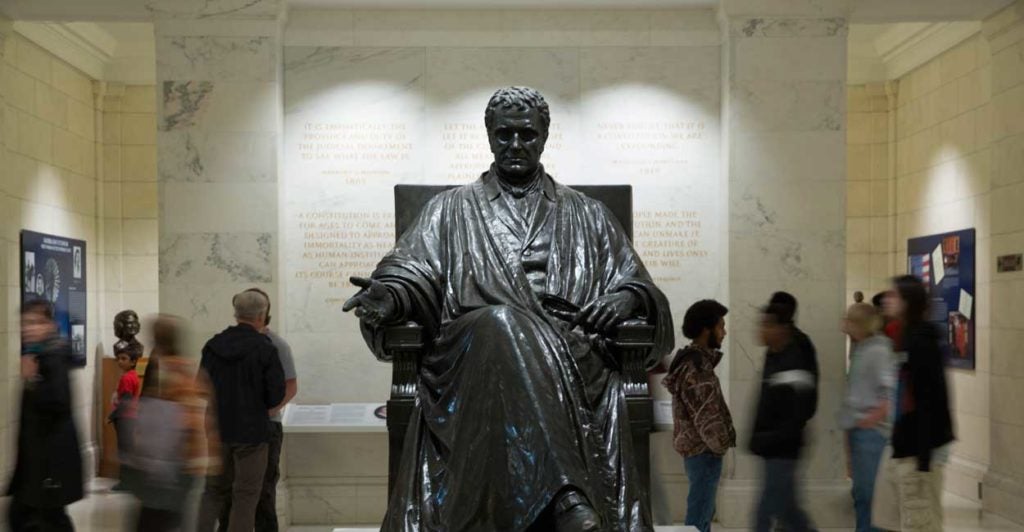

“John Marshall: The Man Who Made the Supreme Court” creates a full picture of America’s greatest chief justice.

In our era, the Supreme Court ranks highly in the minds of Americans. Polls consistently show that voters consider vacancies on, and appointments to, the court as one of the most important factors—if not the most important factor—in who they support for the presidency.

In fact, it has reached the point where many Americans worry that the judiciary has become too powerful, that it has catapulted beyond the Founders’ original intent to become not just a co-equal branch with Congress, but perhaps a superior one.

It’s an amazing transformation for a branch of government that Alexander Hamilton called the “least dangerous” in Federalist 78.

The first chief justice, John Jay, had so little regard for the Supreme Court that he quit after just a few years, saying that the institution lacked “the energy, weight, and dignity which are essential to its affording due support to the national government.”

Regardless of the modern debate over the role and power of the Supreme Court, there is little doubt that the man who did the most to develop the “energy, weight, and dignity” of the court in its early years was Marshall.

As usual, Brookhiser does a phenomenal job of bringing historical characters to life—fleshing out their most important contributions to our country while distilling the essential aspects of the subjects’ personalities in a single, relatively short and tightly argued volume.

He gives this treatment to Marshall, who as a young man served under George Washington in the Continental Army and quickly rose in American politics upon the conclusion of the Revolutionary War.

Marshall remained a devotee of Washington for his whole life and associated himself with the political ideas of Hamilton. Most consequentially, he became the longest-serving chief justice of the United States after being appointed by John Adams in the final days of his presidency.

What’s remarkable about Marshall is that he shaped the Supreme Court at a time in which his original political party—the Federalists—essentially died out. During his tenure from 1801 to 1835, the party of Thomas Jefferson swept the Federalists from office.

Perhaps adding insult to injury, Jefferson was Marshall’s cousin and a fellow Virginian.

Jefferson was seemingly the only man Marshall hated.

Jefferson reciprocated Marshall’s animosity, telling James Madison in a series of letters that Marshall was prone to “flattery” from Hamilton, and had “lax lounging manners” that made him popular with the people of Virginia.

Jefferson liked to play up his own plain and simple values, but one can read into Jefferson the bitterness of a man beaten at his own populist game.

“All the more reason for Jefferson to dislike him,” Brookhiser writes.

In many ways, Marshall got the last laugh. From his position as chief justice, Marshall corralled majorities on the court—with mostly Jeffersonian justices—to uphold the Hamiltonian commercial system that outlasted the Federalist Party.

Marshall was undoubtedly a Federalist judge who had an active political life as a congressman and secretary of state under Adams. However, he took his constitutional responsibilities seriously and was able to persuade others on the court that his views on the law were the correct ones.

This was in large part due to Marshall’s congenial personality, the camaraderie he built with fellow justices, and his towering intellect. It’s safe to say that Marshall’s judicial legacy is unmatched.

While Marbury v. Madison was Marshall’s most famous decision—it solidified the concept of “judicial review”—contemporaries regarded numerous other cases as far more important and contentious.

Cases such as McCulloch v. Maryland, Barron v. Baltimore, Gibbons v. Ogden dealt with complicated issues of federalism and commerce.

These cases, in part, helped establish a national marketplace free from state interference—a hallmark of the Hamiltonian economic program—though Brookhiser contends that the court decided many of these cases on smaller, incidental points of law.

Marshall’s detractors would criticize his landmark decisions as a gateway to an ever-expanding role for the federal government. But is Marshall really to blame for this?

In early American history, as opposed to today, there was a greater tendency for states to overstep their constitutional power, not the federal government, which had very little direct involvement in the lives of citizens.

“States had many powers reserved to them, but where a power was given to the federal government, Marshall and his Court defended it zealously,” Brookhiser writes.

Most importantly, according to Brookhiser, Marshall successfully defended the Constitution as “the people’s supreme act.”

“It was, as Marshall wrote in McCulloch, a government of the people, emanating from them, its powers granted by them, to be exercised on them and for their benefit,” he writes, adding:

Marshall devoted his decades as chief justice to explicating and upholding the people’s government against the attacks of men he deemed demagogues in Congress, in the states (including his own Virginia), and in the White House (including his own cousin).

Marshall was undoubtedly one of the great men in an age of many great men. Though he had detractors and opponents, he drew the respect of Americans from across the political spectrum who recognized his talent, character, and critical place in establishing our early constitutional system.

President Andrew Jackson, who had been a ferocious political rival, delivered one of the most eloquent and succinct tributes to Marshall when the chief justice died in 1835. Jackson said:

I sometimes dissented from the constitutional expositions of John Marshall, [but] I have always set a high value upon the good he has done for his country. The judicial opinions of John Marshall were expressed with the energy [and clarity] which were peculiar to his strong mind, and give him a rank among the greatest men of his age.

Today, a time in which young Americans are losing touch with this country’s past, it’s vitally important to restore the lives of those who made America great to begin with—if only to give ourselves a better perspective of our world in full beyond the 24-hour news cycle and the chaos of modern life.

We can learn so much about the world and ourselves by studying the lives of Americans such as Marshall, who, though fallible and all too human, did so much to establish our infant republic and make it the envy of the world.