President Donald Trump isn’t on the ballot, but will face the biggest electoral test of his presidency so far during Tuesday’s midterm election—one that may well end in repudiation or vindication.

History is not on any president’s side in a midterm election. Since 1862, the president’s party on average loses 32 House seats and more than two Senate seats in a midterm.

And in the 47 midterms since 1826, the president’s party lost seats in 41 of them.

Several scenarios could play out.

The opposition party could gain what President Barack Obama called a “shellacking” when Republicans won 63 House seats in 2010. It could be a rare victory for the president’s party—which occurred only three times in the past 100 years: 1934, 1998, and 2002.

Another likelihood is somewhere in between, such as in 1962 and 1990, when the president’s party suffered only modest losses.

Here’s a look at the shellackings, triumphs, and could’ve-been-worse midterm outcomes that helps put the 2018 contests into perspective.

- 1826 and the First Blue Wave

The public had a bad taste in its mouth from the deadlocked 1824 presidential election. Because no candidate had a majority of electoral votes, the election went to the House of Representatives.

House Speaker Henry Clay threw his support behind John Quincy Adams in his victory over Andrew Jackson. Jackson and his supporters called it a “corrupt bargain” when Adams named Clay his secretary of state.

New factions were born, replacing the old Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties. Adams, son of the nation’s second president, represented the National Republicans; Jackson supporters called themselves Democrats.

Jackson’s political forces targeted House members who voted for Adams in the House showdown but whose constituents voted for Jackson—making 1826 a referendum on 1824.

In 1826, Democrats won 113-100 majority in the House and also took a majority in the Senate, which at the time was not directly elected.

2. Republicans’ First Victory in 1858

President James Buchanan’s Democratic Party was divided over the issue of slavery, even as Buchanan backed the new state of Kansas having a pro-slavery constitution.

This made room for the infant, anti-slavery Republican Party to win a plurality in the House of Representatives—enough to take control.

The American Party and the Whigs had nearly collapsed, but still managed to elect some members in 1858. Although Republicans were four seats shy of a majority, they formed a governing coalition.

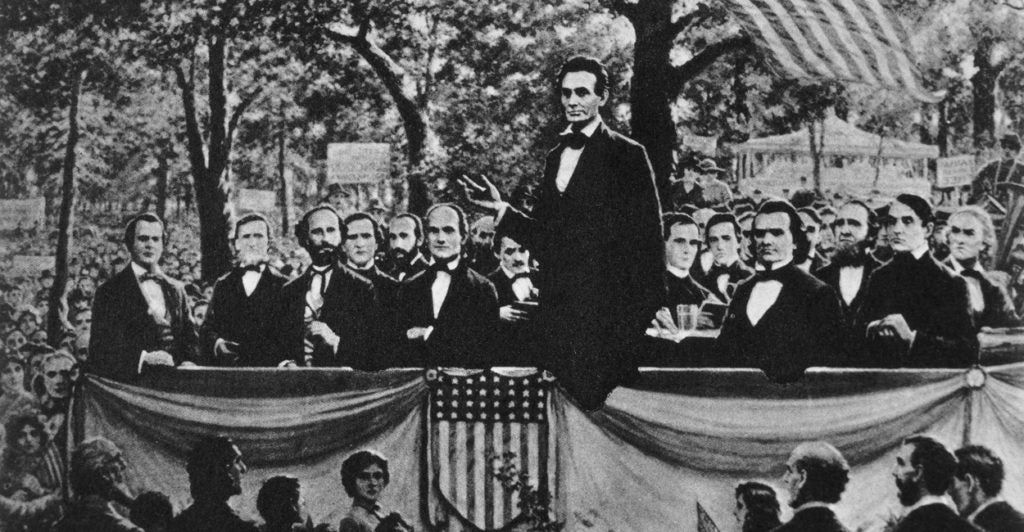

This would be the last midterm congressional election before the Civil War. One famous Republican lost that year.

Though U.S. senators were not directly elected at the time, Senate candidates campaigned and state legislative races served as proxy Senate elections.

This was the year when a former one-term House member, Republican Abraham Lincoln, gained national prominence for his failed Senate bid against the incumbent Democrat, Stephen Douglas.

The race gained national attention largely because Douglas was widely presumed to be the Democrats’ next presidential nominee, and he was.

Lincoln and Douglas would face one another in a 1860 rematch for the presidency, with a different result.

3. The 1874 Democratic Comeback

After the Civil War, the Democratic Party was identified as the party of the vanquished Confederacy, making it largely a regional party in the South.

To rub it in, Republicans conducted what came to be called the “bloody shirt campaign,” reminding voters that maybe not every Democrat was a rebel but every rebel was a Democrat.

Nearly a decade after the end of the war, this blot began to fade as Democratic congressional candidates won even in northern states.

The GOP controlled two-thirds of Congress after Ulysses S. Grant’s landslide re-election as president in 1872. The Democrats were so beleaguered that they cross-endorsed Liberal Republican nominee Horace Greeley in 1872 instead of fielding their own candidate. The Liberal Republican Party was a splinter party of Republicans who were unsatisfied with Grant policies.

However, the public was growing frustrated with corruption in the Grant administration and fatigued by Reconstruction in the South. Northerners wondered why federal troops still had to remain in southern states. Making matters worse for Republicans was the Economic Panic of 1873.

In the 1874 midterm, Republicans lost an astonishing 96 seats in the House of Representatives as Democrats took 168 seats, Republicans held 108, and independents held 14. Independents won some House races, but Democrats won most. Republicans retained control of the Senate.

After the disputed presidential election of 1876 between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden, the House majority had enough clout to force a compromise on the deadlocked result and push a Republican administration to end Reconstruction.

4. Republicans’ Record Gains of 1894

In 1892, conservative Democrat Grover Cleveland was the first president re-elected to nonconsecutive terms. But that second term included an economic downturn in 1893 and a major coal strike.

Two decades after being trounced in 1874, Republicans more than made up for their losses, winning 116 House seats and five Senate seats. Smithsonian magazine called it “the biggest wipeout on record.”

Democrats lost seats in their southern strongholds of Alabama, Texas, Tennessee, and North Carolina when Republican and Populist parties in those states agreed to endorse the same candidate. Two years later, Republican William McKinley would follow up on the momentum to win the presidency.

5. The 1946 Republican Revival

After the Great Depression, the Republicans were basically seen as the party of former President Herbert Hoover, losing routinely to Democrats backing popular President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives.

After Roosevelt’s death in 1945, Vice President Harry Truman seemed like a weak replacement, despite presiding over final victory in World War II.

The postwar economy began to lag, and the Cold War with the Soviet Union became the central issue. Republicans pushed the slogan “Had Enough?” They won 56 House seats and 13 Senate seats. The GOP hadn’t held both Houses since 1928.

The new majority proved a good foil for Truman to run against in 1948, as he lambasted the “do nothing” Congress on his way to a surprise victory over Republican Thomas Dewey.

6. 1974 Watergate Babies

The Democrats already had a congressional majority in 1974. But after Republican Richard Nixon resigned the presidency and three months into the presidency of his former vice president, Gerald Ford, the GOP was demolished in Congress.

The combination of Ford’s pardoning of Nixon and an energy crisis bolstered Democrats to gain 49 House seats for a two-thirds majority, and to gain four Senate seats.

“In 1974, after Watergate, was one of the big ones,” Gary Rose, chairman of the political science department at Sacred Heart University, told The Daily Signal. “There was a distaste for President Nixon, and what the Republicans did with Watergate.”

The newly elected Democrats were known as “Watergate babies.” Because many of the new Democrats were northern liberals, it moved the trajectory of the party away from the southern moderates who had held most of committee chairmanships.

7. The Gingrich Revolution of 1994

President Bill Clinton, elected in 1992, was immediately under scrutiny because of scandals such as the one surrounding the Whitewater real estate development in Arkansas.

Clinton raised taxes, but failed to get a health care bill through Congress. He accomplished the acceptance of gays in the military with his “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy—not a popular move at the time.

“Clinton took a hit in 1994,” Rose said. “The Clinton presidency was adrift in 1994.”

With this backdrop, Rep. Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., and other GOP members introduced the “Contract with America,” which included initiatives to return the country to fiscal responsibility.

For the first time since 1952, Republicans won both houses of Congress, capturing 53 House seats and seven Senate seats. Gingrich became speaker of the House.

Clinton moved decisively to the center after losing Congress, declaring that “the era of big government is over” in his 1996 State of the Union address en route to a re-election victory over Republican nominee Bob Dole that November.

Recent ‘Wave’ Elections

President George W. Bush’s second midterm was far more disappointing than his first, as Democrats recaptured the House and Senate for the first time in 12 years.

Democrats picked up 31 seats in the House to make Rep. Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., the first female speaker of the House. In the Senate, Republicans lost six seats; two independents who caucused with Democrats gave the party a 51-vote majority.

Pelosi’s speakership lasted only four years. After Democrat Barack Obama’s victory in the 2008 presidential race, the tea party movement erupted and Republicans recaptured the House, winning 63 seats. Although Democrats held the Senate, Republicans picked up six seats.

“Obama wasn’t loathed, but the tea party movement felt the country was moving in a direction it didn’t want to go, with a big health care bill, expanding the role of government, more spending and in the middle of a recession,” said Rose, of Sacred Heart University. “And, you can’t discount, for some, there was a backlash against the first African-American president.”

Obama won re-election in 2012, but Republicans came back in the 2014 midterm to win nine Senate seats and take the majority. The GOP also won 13 more House seats.

Not So Bad

On three occasions in the last century, a president’s party actually gained seats in Congress. This happened with Democrat Franklin Roosevelt in 1934, Democrat Bill Clinton in 1998, and Republican George W. Bush in 2002.

But some elections are neither a bloodbath nor a victory for the president.

In the 1960 race for president, Democrat John F. Kennedy squeaked by to victory in a close race against Republican Richard Nixon.

Chicanery was widely suspected. But, in time, Kennedy became popular for his handling of the Cuban missile crisis.

In the 1962 midterm elections, Republicans picked up just four seats in the House and three in the Senate. Kennedy still had a Democratic majority when he was assassinated in November 1963 during a political trip to Texas.

In 1988, George H.W. Bush won a landslide victory to succeed fellow Republican Ronald Reagan as president, but it didn’t carry over to the midterms. Still, it wasn’t a horrible outcome, given the history of midterms.

Democrats won eight House seats and just one Senate seat in 1990. This made little difference, as the party already controlled both chambers of Congress.