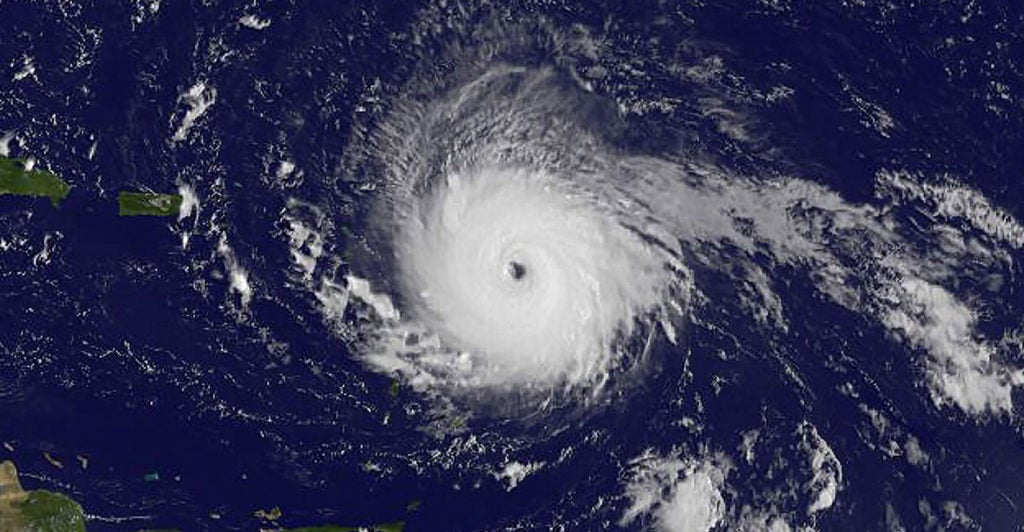

Hurricane Alberto, the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season’s first named storm, already has brought rain and chaos from the Florida panhandle to the Great Lakes region.

In 2017, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria also hit the homeland hard, costing $50 billion to $100 billion in damages each. The U.S. can expect more of the same as this summer unfolds, but it may find its national disaster relief apparatus underprepared in budget and resources.

The overburdened Federal Emergency Management Agency faces several problems: a regularly depleted Disaster Relief Fund, an unsustainable National Flood Insurance Program, and regulations that hinder its post-disaster economic flexibility.

Because of the 1988 Stafford Act and subsequent regulation, the federal government pays at least 75 percent of recovery costs of any disaster that costs more than $1.46 per capita. This means communities that suffer as little as $5 million in damages qualify for the relief, which encourages states to run the Disaster Relief Fund dry for smaller disasters. Then, when funds run short for larger disasters, additional congressional appropriations become necessary.

The issue is compounded by the flood insurance program’s inaccurate risk-mapping, indiscriminate policy-issuing, and additional subsidies. Already $25 billion in debt, the program encourages development in flood-prone areas by fully insuring homeowners based on old or privileged property risk assessments—only about half of which validly reflect higher risk levels.

Finally, the Jones Act and other regulations unnecessarily impede vital economic flexibility during recovery. The Jones Act requires that shipping between U.S. ports be done by U.S.-made and -manned ships, often frustrating seaside and even inland recovery efforts by hindering the cheap delivery of needed goods.

The Foreign Dredge Act of 1906 similarly restricts would-be dredgers. Other regulations harmfully restrict first responders and community rebuilding.

The Department of Homeland Security and Congress can take steps to solve these problems. Homeland Security should thin the number of small disasters FEMA responds to by raising the per-capita standard for disaster declarations.

Meanwhile, Congress can alter the federal cost share so only the largest disasters receive 75 percent funding. This would re-emphasize state roles in dealing with local disasters, which would encourage them to better prepare.

At the same time, Congress should cease subsidizing risk through the National Flood Insurance Program and mitigate regulatory obstacles to recovery. Lifting the program’s monopoly on flood insurance and letting private insurers compete would use private insurers’ free-market profit incentive and accurate local knowledge of risk. Premiums would reflect the risk inherent to the given area and, as a result, not encourage continued risk.

Additionally, regulations harmful to recovery, such as the Jones Act, should be removed by Congress or waived by the administration where possible.

These measures would prepare America for the largest disasters and make response and recovery more robust for the smaller ones. Better accounting for risks and loosening regulations will make community rebuilding quicker, easier, and more sustainable.

The Department of Homeland Security and Congress should pursue these and other reforms to make sure the U.S. is prepared for hurricane season.