Carter G. Woodson, noted scholar, historian, and educator, created “Negro History Week” in 1926, which became Black History Month in 1976. Woodson chose February because it coincided with the birthdays of black abolitionist Frederick Douglass and President Abraham Lincoln.

Americans should be proud of the tremendous gains made since emancipation. Black Americans, as a group, have made the greatest gains, over some of the highest hurdles, in a shorter span of time than any other racial group in mankind’s history.

What’s the evidence? If one totaled black income and thought of us as a separate nation with our own gross domestic product, black Americans would rank among the world’s 20 richest nations. It was a black American, Colin Powell, who, as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, headed the world’s mightiest military.

There are a few black Americans who are among the world’s richest and most famous personalities.

The significance of these achievements is that in 1865, neither a former slave nor a former slave owner would have believed that such gains would be possible in a little over a century. As such, it speaks well of the intestinal fortitude of a people. Just as importantly, it speaks well of a nation in which such gains were possible. Those gains would have been impossible anywhere other than the U.S.

Putting greater emphasis on black successes in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds is far superior to focusing on grievances and victimhood. Doing so might teach us some things that could help us today.

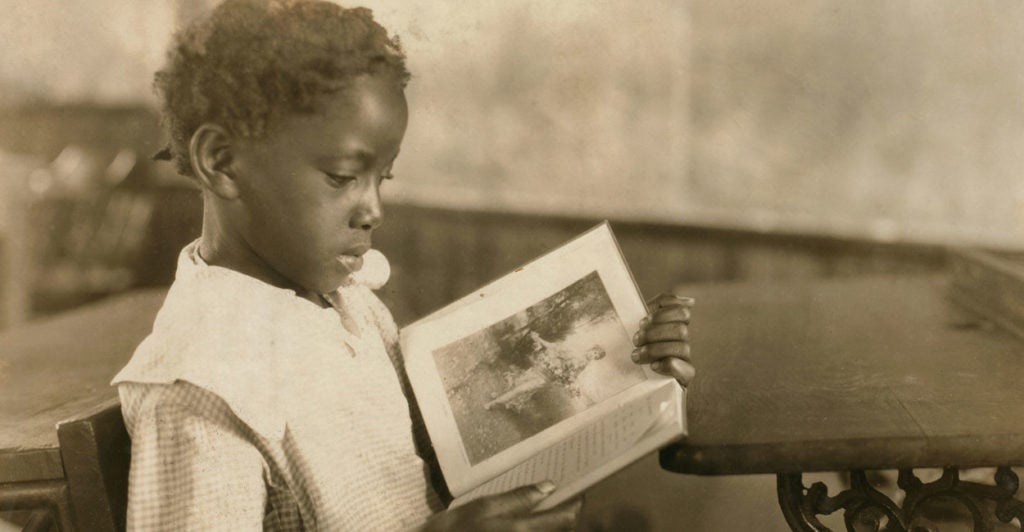

Black education today is a major problem. Let’s look at some islands of success from yesteryear, when there was far greater racial discrimination and blacks were much poorer.

From the late 1800s to 1950, some black schools were models of academic achievement. Black students at Washington’s racially segregated Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, as early as 1899, outscored white students in the District of Columbia schools on citywide tests.

Thomas Sowell’s research in “Education: Assumptions Versus History” documents similar excellence at Baltimore’s Frederick Douglass High School, Atlanta’s Booker T. Washington High School, Brooklyn’s Albany Avenue School, New Orleans’ McDonogh 35 High School, and others.

These excelling students weren’t solely members of the black elite; most had parents who were manual laborers, domestic servants, porters, and maintenance men. Academic excellence was obtained with skimpy school budgets, run-down buildings, hand-me-down textbooks, and often 40 or 50 students in a class.

Alumni of these schools include Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice (Frederick Douglass); Gen. Benjamin Davis; Dr. Charles Drew, a blood plasma innovator; Robert C. Weaver, the first black Cabinet member; Sen. Edward Brooke; William Hastie, the first black federal judge (Dunbar); and Nobel laureate Martin Luther King Jr. (Booker T. Washington).

These examples of pioneering success raise questions about today’s arguments about what’s needed for black academic success. Education experts and civil rights advocates argue that for black academic excellence to occur, there must be racial integration, small classes, big budgets, and modern facilities. But earlier black academic successes put a lie to that argument.

In contrast with yesteryear, at today’s Frederick Douglass High School, only 9 percent of students test proficient in English, and only 3 percent do in math. At Paul Laurence Dunbar, 12 percent of pupils are proficient in reading, and 5 percent are proficient in math. At Booker T. Washington, the percentages are 20 in English and 18 in math.

In addition to low academic achievement, there’s a level of violence and disrespect to teachers and staff that could not have been imagined, much less tolerated, at these schools during the late 1800s and the first half of the 20th century.

Many black political leaders are around my age, 81, such as Rep. Maxine Waters, Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton, D-D.C., and Jesse Jackson. Their parents and other authorities would have never accepted the grossly disrespectful, violent behavior that has become the norm at many black schools.

Their silence and support of the status quo makes a mockery of black history celebrations and represents a betrayal of epic proportions to the blood, sweat, and tears of our ancestors in their struggle to make today’s educational opportunities available.