Governors are known for cutting ribbons to celebrate new employers coming to their state, but it is rare for a governor to remove the scarlet letter from someone convicted of a crime.

Speaking on the American principle of second chances at the Governors’ Justice Series, Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin and Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds shared powerful stories of prison reform in their respective states.

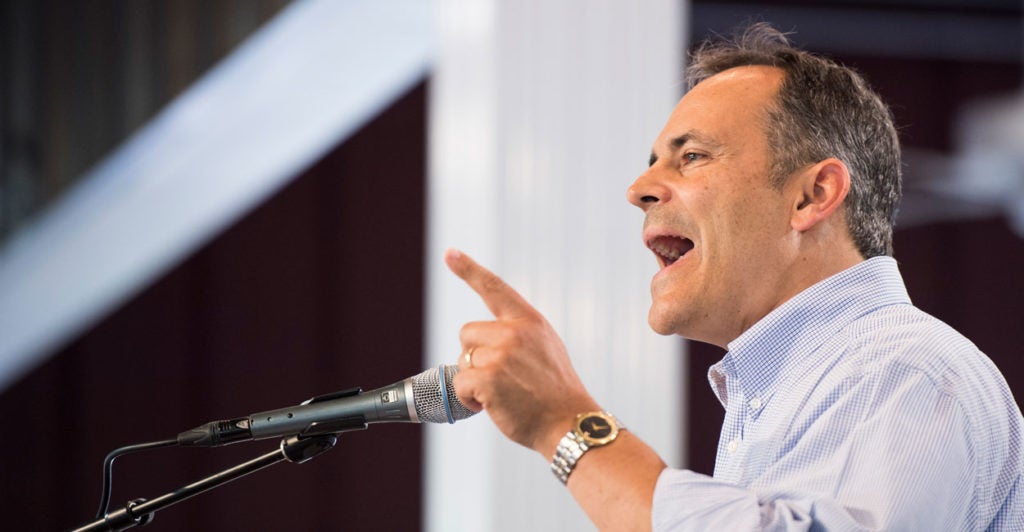

Bevin, a conservative Republican, spoke to the positive economic impact of criminal justice reform. Having implemented job training programs in Kentucky state prisons, Bevin shared his commitment to policies that offer opportunities for redemption. “America is the land of second chances,” Bevin said.

At the Council of State Governments Public Safety Summit, days prior to the Governors’ Justice Series, Bevin noted that he couldn’t think of a more solemn responsibility that he has as governor than carefully reviewing applications for pardons to identify those who are deserving of a second chance.

Bevin spent many hours poring over individual cases with his staff and issued 10 pardons this July.

Both Bevin and Reynolds have met face to face with prisoners to gain a deeper understanding of how criminal justice reform changes lives. Reynolds, who has been heavily involved with women prisons in her state, testified to the importance of rehabilitative programs in helping Americans who have made mistakes choose a better path.

She highlighted successes in reducing reoffending through vocational programs that prepare those in prison for careers and treatment for those struggling with addiction and mental illness.

“You can face significant challenges and obstacles and still turn your life around,” said Reynolds. By reducing reoffense rates, also called recidivism, public safety is strengthened and taxpayer dollars are saved.

In fact, since 2007, more than two-thirds of all states have implemented corrections reforms through a process called justice reinvestment that brings all stakeholders to the table to identify data-driven solutions to lower crime and costs to taxpayers.

It is only fitting that the Governors’ Justice Series was hosted in Austin, as Texas was one of the first states to implement a justice reinvestment plan back in 2007.

Instead of building 17,000 more prison beds that projections indicated would otherwise be needed, Texas expanded alternatives to incarceration such as drug courts and mental health treatment, as well as in-prison treatment programs to reduce the number of people who would return to prison.

Since then, Texas’ crime rate is down more than 30 percent and its incarceration rate has fallen more than 20 percent.

Between 2010 and 2015, some 31 states succeeded in reducing both crime and incarceration rates. Although states have wisely customized solutions to match their own unique populations and challenges, several common threads have emerged.

First, many states have revised their sentencing policies to focus on locking up people they are afraid of, not those they are just mad at. This has involved changes such as reducing penalties for possession of small amounts of drugs and instead holding those with addiction accountable through probation supervision and community-based treatment programs.

For example, in 2017, North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum helped spearhead the state’s comprehensive reinvestment package, which included a reduction in penalties for possession and more treatment.

Burgum noted: “Building new jails and incarcerating those with the chronic disease of addiction and in desperate need of help is the most expensive and least effective course of action.”

Second, many states have sought to improve the effectiveness of the probation and parole supervision so more people succeed instead of being sent back to prison either for new crimes or technical violations such as missing meetings.

Led by then-Democratic Gov. Bev Perdue and a Republican Legislature, in 2011, North Carolina adopted a justice reinvestment plan that created an alternative to prison revocation for those on supervision who violated the terms of their probation but did not commit a new offense.

The new approach involved “quick dips”—short jail stays of a couple of days that sent a swift and certain message that compliance was expected while still enabling the person to keep their job. The result has not only been fewer revocations to prison and therefore lower costs, but most importantly, fewer new crimes by probationers.

Finally, states are working to reduce barriers that ex-offenders face in securing employment. For example, in March 2017, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey signed an executive order requiring state agencies to provide written justification for policies excluding those with a criminal background from obtaining an occupational license.

In commemorating the opening of a new factory, a governor celebrates his state’s economic potential. With criminal justice reform, governors are increasingly tapping into their state’s human potential while also doing right by public safety and their state’s taxpayers.