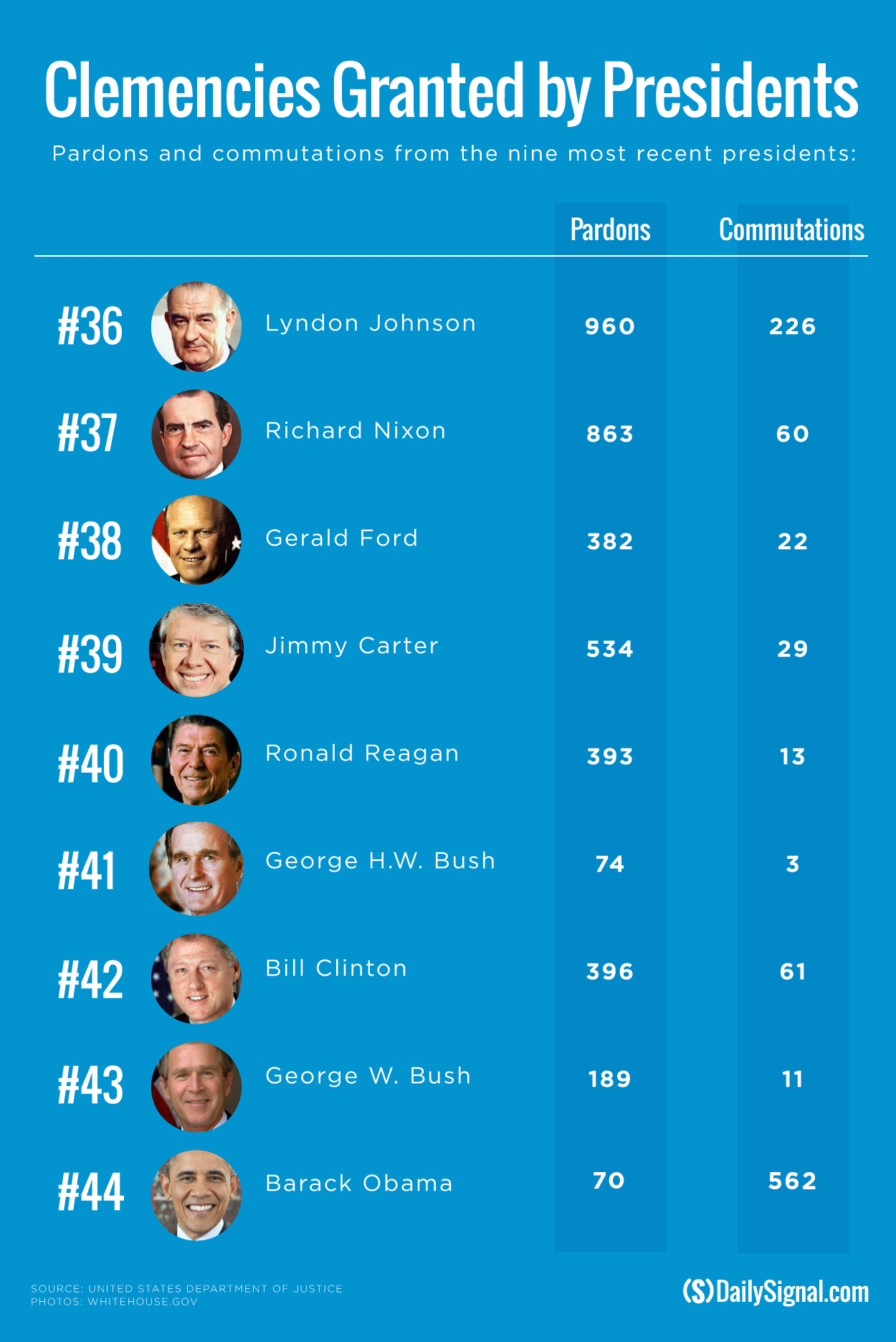

Those of us concerned over President Barack Obama’s excessive use of his power under Art. II, §2, Cl. 1 of the Constitution to grant pardons and commutations to hundreds of drug dealers, many of whom also were convicted of firearms offenses (and therefore, contrary to what the president said, not nonviolent offenders), should realize that he is not the first president to misuse that authority.

When former President Bill Clinton was reminiscing this week in his prime-time speech to the nation at the Democratic National Convention, he forgot to mention the scandalous pardons he issued at the end of his administration.

My colleague, Paul Larkin Jr., has a very informative article in the summer issue of the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy on “Revitalizing the Clemency Process.” He points out that:

Recent presidential abuses of the pardon power have poisoned the well. For example, President Bill Clinton was twice guilty of that crime. He offered conditional commutations to the members of a Puerto Rican terrorist group, the Armed Forces of National Liberation (or FALN), very possibly to enlist the support of the Puerto Rican community for his wife Hillary’s upcoming Senate race and for Vice President Al Gore’s campaign to replace him as president. Clinton also used his clemency power promiscuously in his last 24 hours in office, granting pardons and commutations the same way that a drunken sailor on shore leave spends money. Clemency recipients were often people (or their representatives) with strong White House connections or who had contributed generously to the president’s party or his own presidential library. Clinton’s clemency decisions have left a pall over the entire process.

Larkin has a keen legal mind as well as a sharp sense of humor. On reflection, the analogy Larkin uses seems a bit unfair. Any insult to drunken sailors is certainly unintentional. But this is a serious issue that the public should critically examine and that voters should think about because presidents have the closest thing to absolute power when it comes to pardons.

There is almost no limit to a president’s authority to “grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States.” In fact, the only limitation is that he (or she) cannot issue pardons “in cases of impeachment.”

In January, the lawyer at the U.S. Justice Department, Deborah Leff, who was the head of the Office of the Pardon Attorney, resigned after less than two years in office. This office is charged with conducting thorough and comprehensive reviews of all applications for pardons and commutations and making recommendations to the attorney general and the president on which ones should be granted and which ones do not merit consideration.

In her resignation letter to Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates (the number two official at the DOJ), Leff said she was resigning because she was “unable” to carry out her job “effectively.” That inability was due to the Justice Department not providing “the resources necessary for my office to make timely and thoughtful recommendations on clemency to the president.”

Because of Obama’s “Clemency Initiative” for drug crimes (which she supported), she had “been instructed to set aside thousands of petitions for pardon and traditional commutation.” She was “deeply troubled” by the decision of the department to deny her “all access to the Office of White House Counsel, even to share the reasons for our determinations in the increasing number of cases where you have reversed our recommendations.”

Leff complained that the pardons office had neither the attorneys nor the support staff necessary to review “the requests of thousands of petitioners seeking justice.”

No one denies that there are some individuals convicted of drug offenses who received excessive sentences under some of our more draconian mandatory minimum sentencing laws whose sentences should be commuted. Since Leff’s resignation, procedures have apparently been improved and the new acting pardons attorney is using personnel in the offices of U.S. attorneys around the country to help review applications for pardons and commutations.

Everyone should be able to agree that no action should be taken by any president until and unless Justice Department lawyers have undertaken a detailed review of the merits of such cases, including an in-depth look at the character and personal history of felons in federal prison who are seeking absolution or a sentence reduction for their crimes. That is how to conduct the pardon process.

Unfortunately, we know that is not what matters to some presidents. What matters is petitioners with the right friends in high office, who have made the right political contributions, who can provide a political boost for certain candidates, or who will help a president meet a particular political goal, regardless of the individual circumstances and merits of the petitioners’ crimes.