Liberals leap to put down Ronald Reagan even when they are writing about someone else. They simply cannot accept that Reagan was one of the most successful and remains one of the most popular presidents in American history.

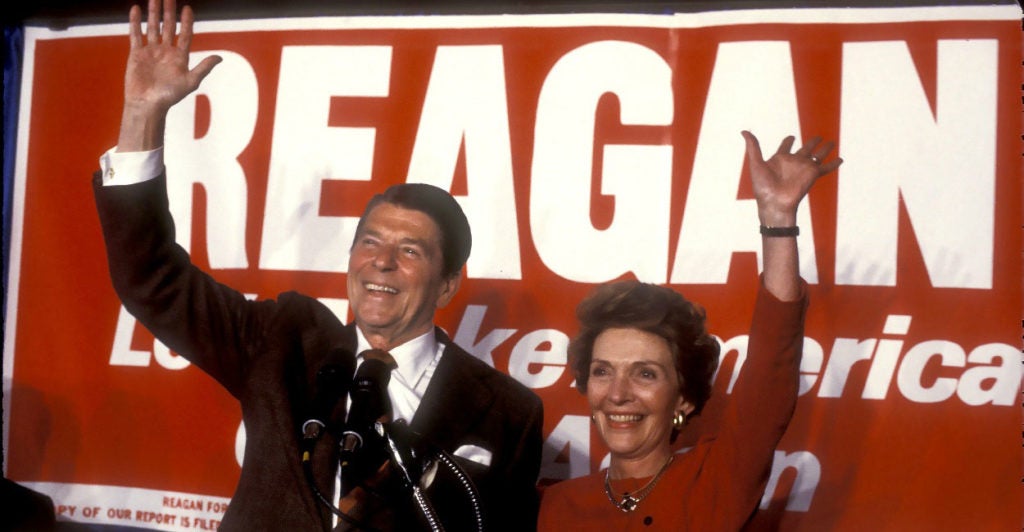

For example, in a critical essay about Donald Trump in the Sunday New York Times, the novelist Kevin Baker writes that “the modern politician Mr. Trump most closely resembles … is Ronald Reagan.”

After referring to Reagan’s “self-aggrandizing, demagogic side,” Baker packs more errors about Reagan’s life and career in one paragraph than Edmund Morris did in all of his grievously disappointing biography, “Dutch.”

Baker describes himself as a novelist, historian, journalist, political commentator, gadfly—he omits “sloppy, careless, feckless researcher.” Let us begin setting the record straight with Baker’s characterization of Reagan the actor as “a second-tier performer.”

In fact, with the release of the highly popular movie “King’s Row,” with the famous line, “Where’s the rest of me?” Reagan became one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, drawing more fan mail at Warner Brothers Studios than any other actor except Errol Flynn and becoming the first film actor to sign a contract worth a million dollars.

Taking advantage of Reagan’s new status, Warner announced that he and Ann Sheridan would co-star in a dramatic story of war refugees in French Morocco.

However, on April 18, 1942, 2nd Lt. Ronald Reagan reported for active duty, putting his acting career on hold and denying moviegoers the chance to see Reagan and Sheridan in the iconic movie “Casablanca.”

Baker perpetuates some of the hoariest myths about Reagan. Asserting that his speeches and debates “were laced with convenient untruths and slanders,” Baker refers to an alleged “Chicago ‘welfare queen’ tooling around in her Cadillac.”

It is true that in 1976, when he was challenging President Gerald Ford for the Republican presidential nomination, Reagan frequently referred to a “welfare queen” who used “80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers, to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans benefits for four nonexistent deceased husbands as well as welfare. Her tax-free cash income alone has been running $150,000 a year.”

The unparalleled greed of the “welfare queen” shocked listeners and was skeptically received by a cynical press. Economist Paul Krugman spoke for most liberals when he wrote years later that “the bogus story of the Cadillac-driving welfare queen [was] a gross exaggeration of a minor case of welfare fraud.”

What was truly gross was the failure of the press to determine the truth about Linda Taylor, the “welfare queen.”

To his credit, John Levin, the executive editor of the liberal blog Slate, went looking in 2013 for Taylor and discovered that Reagan had indeed erred—he had underestimated the extent of her felonies.

She had used three Social Security cards, 21 names, 31 addresses, and 25 phone numbers while “tooling around” Chicago in three different luxury cars—a Cadillac, a Lincoln, and a Chevy station wagon. She had used as many as 80 different names and received at least $150,000.

The executive director of the Legislative Advisory Committee on Public Aid commented: “She is without a doubt the biggest welfare cheat of all time.”

Baker writes that presidential nominee Reagan made his first speech of the 1980 general campaign at a fair in Neshoba County, Mississippi, where three civil rights organizers had been murdered by the Ku Klux Klan 16 years earlier. Reagan aides, including Richard Wirthlin, had urged Reagan to cancel the talk because the KKK still operated there. But Reagan had promised Mississippi Republicans he would attend the fair and, always a man of his word, he did so.

In his remarks, punctuated with jokes about his Democratic opponent, Jimmy Carter, Reagan talked about his successful welfare reform in California and the power of federalism. “I believe in states rights,” he said, and promised to “restore to states and local governments the power that properly belongs to them.”

That was the sole reference to “states rights” in his 15-minute talk. Yet Krugman and other liberals have characterized Reagan’s Neshoba speech as public approval for “good old-fashioned racism” and a racist Southern strategy.

But they do not report that Carter kicked off his 1980 campaign in the Deep South, in Tuscumbia, Alabama, with the one-time arch-segregationist George Wallace on the platform behind him. Nor do they criticize the 1988 Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis for speaking at—you guessed it—the Neshoba County Fair.

For his part, Baker omits that Reagan’s very next campaign speech after Neshoba was to the National Urban League in New York City. Declining to pander, Reagan declared that the solution to the economic problems of the black family was not more federal programs but “a bigger pie so that everyone will have a chance to be better off.”

According to biographer Craig Shirley, Reagan pointed to his record of black advancement while governor of California when the percentage of African-Americans hired in the state government increased 23 percent. He asked league members not to look at him as a “caricatured conservative.”

But that is precisely how Baker and Krugman looked at Reagan.

Not so the liberal prize-winning historian Garry Wills, who after writing an early critical book about Reagan switched significantly, listing the president’s qualities as follows: “Self-assurance without a hectoring dogmatism, pride without arrogance, humility without creepiness, ambition without ruthlessness, accommodation without mushiness. How can you beat that?”

You can’t.