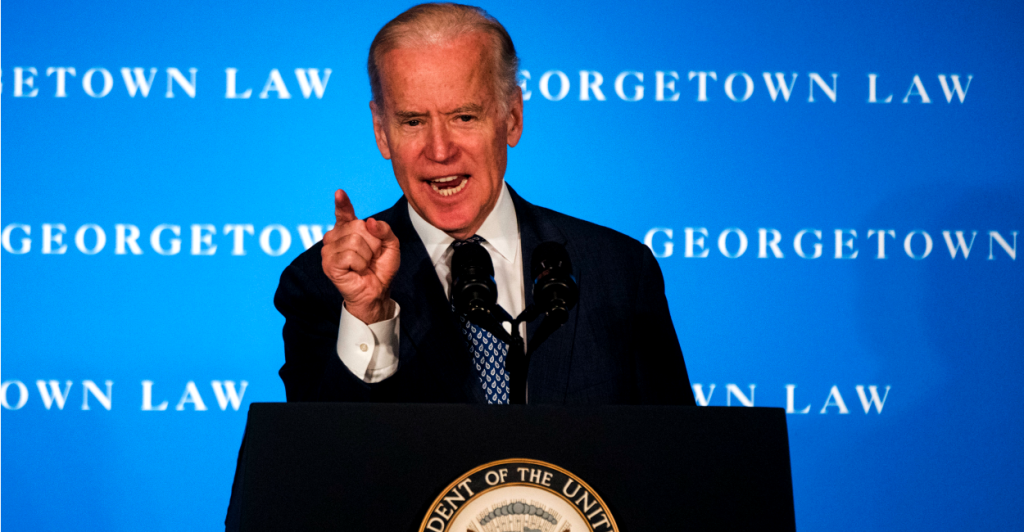

Vice President Joe Biden tried again to walk back his past objections to confirming any Supreme Court nominees five months before the 1992 presidential election. Those remarks, he argued, are irrelevant to the current Supreme Court controversy.

Speaking at Georgetown Law School, Biden argued Thursday that he never advocated blocking any of President George H.W. Bush’s potential nominees altogether. Instead, he opposed “nomination of an extreme candidate without proper Senate consultation.”

“I made it absolutely clear that I would go forward with the confirmation process as [Senate Judiciary Committee] chairman,” Biden said, referring to a floor speech he made in June 1992, “… if the nominee were chosen with the advice and not merely the consent of the Senate, just as the Constitution requires.”

Since dredging up his speech in February, Republicans have used the vice president’s words to justify their blockade of Merrick Garland’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

“Once the political season is under way,” Biden argued at the time as a senator representing Delaware, “… action on a Supreme Court nomination must be put off until after the election campaign is over. That is what’s fair to the nominee and is central to the process.”

But Biden on Thursday accused GOP senators of deceptively cherry-picking from his remarks and “neglect[ing] to quote my unequivocal bottom line.”

To “set the record straight,” Biden quoted from his 1992 floor speech, including this line: “If the president consults and cooperates with the Senate, or moderates his selections, then his nominees may enjoy my support, as did Justice [Anthony] Kennedy and Justice [David] Souter.”

Before Thursday’s speech, Biden had been dogged by Republicans’ arguments that they’re only following “the Biden rule.” They’ve used his words as cover for their pledge not to advance a Supreme Court nominee until President Barack Obama’s successor takes office in January.

A seat on the high court became vacant when Justice Antonin Scalia, a conservative, died unexpectedly Feb. 13. Obama named a veteran appeals court judge, Merrick Garland, to replace him.

The vice president dismissed the “Biden rule” description as “frankly ridiculous” and noted that while chairing the Judiciary Committee, he followed “the Constitution’s clear rule of advice and consent.”

“I was responsible for eight justices and nine total nominees to the Supreme Court,” Biden said, adding:

“And every nominee, including Justice Kennedy in an election year, got an up and down vote [by the Senate]. Not much of the time. Not most of the time. Every single solitary time.”

The vice president played up the possibility of 4-4 split decisions from the Supreme Court, predicting that the court couldn’t rule definitively on important issues, creating a “patchwork Constitution inconsistent with equal justice and the rule of law.”

When a tie occurs, the ruling of a lower court is upheld but does not take national precedent, as would a high court decision.

However, in 1992, Biden dismissed the idea of a split court as a reason for holding confirmation hearings because the impact would be “quite minor compared to the costs that a nominee, the president, the Senate, and the nation would have to pay.”

Qualifying that statement in his Georgetown Law School appearance, Biden said he didn’t worry about that possibility at the time “partly because the period wouldn’t last very long.”

In contrast, Biden said, today’s Republicans would leave the court in limbo “for potentially and likely the next 400 days.”

Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, was quick to slam the Obama administration for trying to “rewrite history.”

“While the vice president and others have tried to recast his 1992 speech as merely a call for greater cooperation,” Grassley wrote in a statement, “they neglect to mention that such cooperation, according to Chairman Biden, was to occur ‘in the next administration,’ and only after the presidential election.”

Though Thursday’s speech was the first time Biden spoke publicly on the issue, he previously attempted to walk back his 1992 statements in several tweets and in a New York Times op-ed.