An annual report examining physician-assisted suicide trends in Oregon shows a growing number of individuals seeking to die under the state’s Death with Dignity Act.

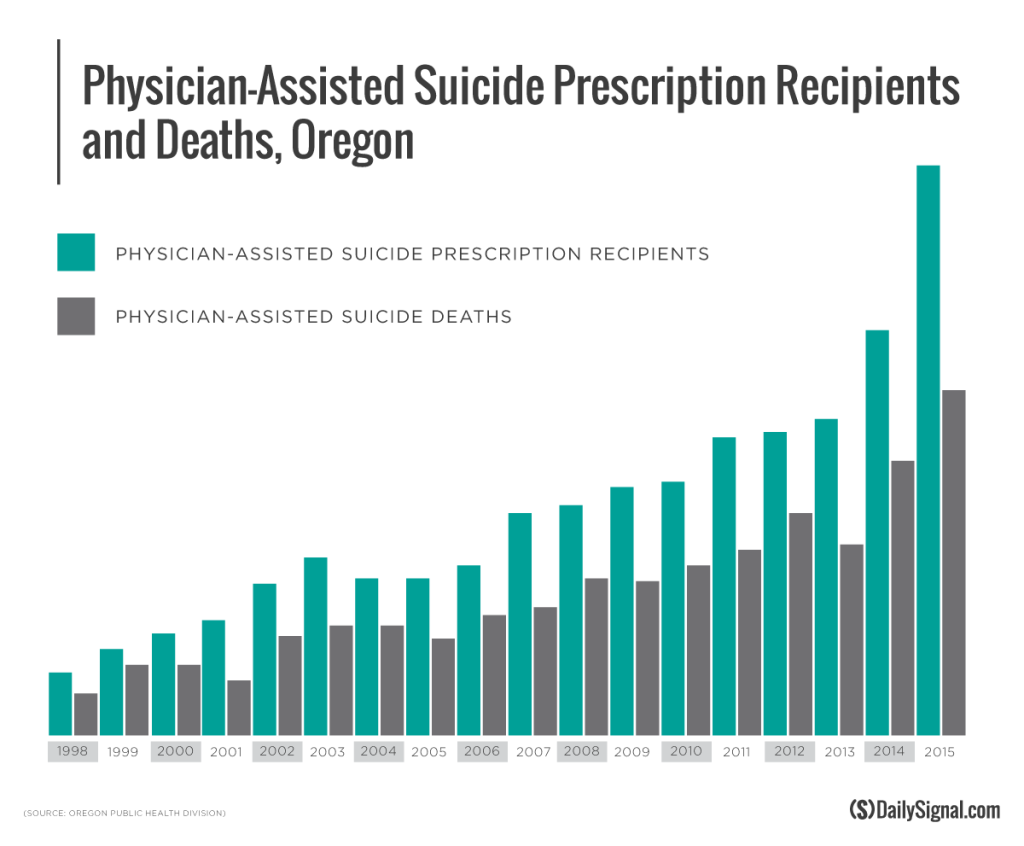

“In the past two years the number of deaths as a result of physician-assisted suicide in Oregon has nearly doubled,” said Ryan T. Anderson, who researches and writes on physician-assisted suicide at The Heritage Foundation. “In the past 15 years, the number has increased sixfold. If physician-assisted suicide is allowed in other states, we are likely to see a similar growth in the number of deaths by suicide across the U.S.”

“This is a tragedy,” Anderson adds, “as it fails to respect the equal dignity of every life.”

In 2015, the Oregon Public Health Division reported that 132 people died using physician-assisted suicide, compared to 105 the previous year. The number of people who received the life-ending prescription increased from 155 in 2014 to 215 in 2015.

Advocates for physician-assisted suicide attribute the rising numbers to a growing acceptance among doctors to prescribe the life-ending drugs.

“As more physicians recognize that a small percentage of terminally ill adults experience unbearable suffering that no medical treatment can relieve, they are more accepting of voluntary requests for aid in dying medication,” Sean Crowley, media relations director at Compassion and Choices, told The Daily Signal.

However, Crowley said the number of terminally ill adults seeking this option will “always be small.”

“While the percentage of terminally ill adults who utilized medical aid in dying rose by a fraction of a percent to less 0.4 percent of all deaths in Oregon last year and may grow slightly in future years, the percentage will always be very small because hospice and palliative care can provide relief for most dying people,” he said.

In 1997, Oregon became the first state in the nation to legalize physician-assisted suicide. It has since been legalized in Washington, Vermont, and most recently California.

Physician-assisted suicide laws, often titled “Death with Dignity” bills, permit mentally competent, terminally ill adults to obtain a prescription for life-ending drugs from their physician.

According to the recently published report, “Oregon Death With Dignity Act: 2015 Data Summary,” the most frequently cited reasons for choosing assisted suicide in the past year were a “decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable,” a “loss of autonomy,” and a “loss of dignity.”

Of those who chose the life-ending option, 78 percent were 65 and older, 93 percent were white and well-educated, and 72 percent had cancer.

While the overall percent of Oregon’s population seeking physician-assisted suicide was small—less than 0.4 percent of the state’s population—critics point out that when applied to states like California that have much higher populations, the numbers quickly grow.

If the rate of physician-assisted suicide deaths in California were the same as Oregon’s rate, that would result in 2,118 deaths a year.

“The current numbers are not the ceiling; they’re the launching pad. Once a society or a state or a culture starts accepting this agenda, the numbers go up,” said Wesley J. Smith, a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute’s Center on Human Exceptionalism and consultant to the Patients Rights Council, adding:

That happens everywhere you see assisted suicide or euthanasia legalized. When you consider a country the size of the United States—even right now using Oregon’s numbers, which keep going up every year—you have well over 10,000 per year who would have assisted suicide, which is not a small number, particularly when you consider that even though we pretend that these are not suicides, these are suicides.

“Raw numbers are irrelevant, because the percentage of people who utilize medical aid in dying will always be low, even it rises slightly from year to year,” Crowley argued, adding:

An independent report published in the Journal of Medical Ethics about the Oregon Death with Dignity Act concluded: “we found no evidence to justify the grave and important concern often expressed about the potential for abuse—namely, the fear that legalized physician-assisted dying will target the vulnerable or pose the greatest risk to people in vulnerable groups.”

Those who oppose “Death with Dignity” laws look to Europe, where three countries—the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland—allow assisted suicide for non-terminal illnesses, including psychiatric disorders like depression and schizophrenia.

A study published Wednesday by JAMA Psychiatry raised serious concerns among opponents, finding that 56 percent of people who were prescribed life-ending drugs refused treatment that could have helped their condition. Of the results, the authors wrote:

The results show that the patients receiving [euthanasia or assisted suicide] are mostly women and of diverse ages, with various chronic psychiatric conditions, accompanied by personality disorders, significant physical problems, and social isolation or loneliness. Refusals of treatment were common, requiring challenging physician judgments of futility.

Compassion and Choices, which brought the issue of assisted suicide to the attention of many Americans through the story of Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old with terminal brain cancer who opted to use physician-assisted suicide, argues that JAMA’s study is irrelevant to the discussion here in the United States because no one is advocating for assisted suicide laws to apply to patients who are not terminally ill or mentally competent.

Critics, however, argue that the evolution is inevitable as more people become accustomed to physician-assisted suicide. Before long, they say, death by suicide will become the new norm.

“I think people have to understand that places like Compassion and Choices are very political and they’re very poll-driven, and they want to get people to accept the premise,” Smith said. “But once people accept the premise that suicide is an acceptable answer to human suffering, why in the world would it be limited to the terminally ill?”

“There are a lot of people who suffer far more profoundly for a far longer period who are not terminally ill than the dying,” Smith remarked. “You see almost everywhere else—Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands—that assisted suicide is not limited to the terminally ill.”

The sentence, “Montana and New Mexico have adopted more restrictive versions of assisted suicide,” was removed from this article after publication.