Republicans hold majorities in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. They got those majorities by making promises that, once elected, they announced they couldn’t keep.

The ongoing leadership shake-up in the House is one outcome of broken promises. But another one may be in the works that has a much more significant and, in the long term, negative impact. It’s an attempt to rid the Senate of one of its most distinguishing and important rules, the filibuster.

Here’s why:

Senate Republican leadership simply can’t find the will or the spine to move any legislation forward that might cause a messy debate on the Senate floor or that President Obama has threatened to veto.

With 54 of the 100 seats held by Republicans, the thinking seems to be that because they don’t have the 60 votes needed to bring every piece of legislation to the floor and because they certainly don’t have the 67 needed to override a presidential veto, there is very little that can be done. So conservatives, this thinking goes, should just focus on winning the presidency in 2016.

That thinking has led some frustrated conservatives, both inside and outside Washington, to call for getting rid of the 60-vote rule so the GOP can start making good on its agenda with a simple majority.

At first blush, it doesn’t sound like a bad idea. But as with many things that sound too good to be true, I figured I should talk it through with an expert on the matter. What follows is my Q&A conversation with Capitol Hill veteran Rachel Bovard, now The Heritage Foundation’s director of policy promotion. As our discussion reveals, getting rid of the filibuster could be a “quick fix” that conservatives come to regret.

Q: What exactly is the filibuster, and why was it created?

A: A filibuster is a debate by one or more senators intended to slow consideration of a bill or nomination. As a parliamentary tactic, the filibuster was designed by the early Senate to ensure that the minority views were heard—that is, to protect the minority from attempts by the majority to shut down debate.

The right of every senator to filibuster was codified in 1917 in Senate Rule 22. Under current Senate rules, each senator can engage in a filibuster unless or until 60 of the 100 senators agree that it is time to end debate. Achieving 60 votes is known as “achieving cloture,” and once cloture is achieved, what was previously unlimited debate time on a particular bill or amendment is now limited to 30 hours, followed by a vote.

The filibuster can apply to legislation, nominations, and many of the [other] matters that the Senate considers.

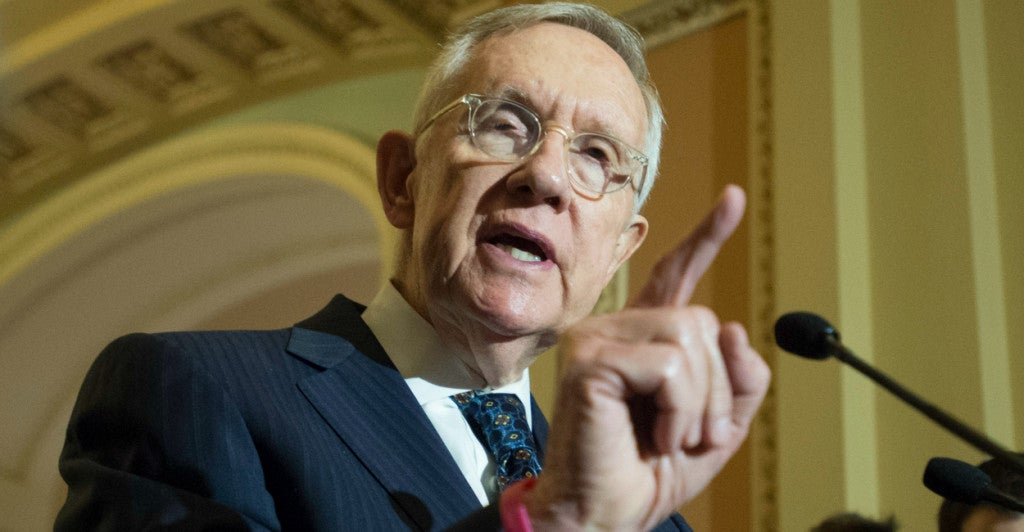

Q: This isn’t the first time there has been a debate over getting rid of, or changing, filibuster rules. How did the 2013 decision by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid [D-Nev.] to “go nuclear” affect this debate?

A: The filibuster applies to legislation, but it also applies to presidential nominees—the people that the president selects, or nominates, to certain positions in the government that must first be confirmed by the Senate.

Prior to 2013, these nominations would sometimes be held up by the Senate’s inability to achieve 60 votes to proceed to a vote on the nomination. In response, then-Majority Leader Reid imposed an unprecedented maneuver and changed the Senate precedents to require only a simple majority vote to move the debate forward on judicial nominations—excluding Supreme Court nominations—and executive nominations, including Cabinet positions.

Q: What was the long-term effect of the nuclear option?

A: When Senator Reid invoked the nuclear option, it had two substantial impacts. First, as a practical matter, President Obama has had a very easy time placing his nominees throughout various levels of government, particularly in the judiciary, where they have lifetime appointments. That means the influence of the nuclear option—and the ease [with] which it has confirmed President Obama’s judges, in particular—will be felt in the judicial branch, and the decisions handed down therein, for years to come.

The second impact is more philosophical, but still significant. In invoking the nuclear option, Senator Reid violated a premise on which the Senate has run for hundreds of years, and that is the deliberate protection of minority rights. While the House is run under majoritarian rule, the Senate is structured to be more deliberative—to give the minority certain rights that ensure their voices are heard.

The Senate’s unique structure also fosters debate and compromise to achieve the bipartisan consensus needed to move major legislation or nominations through to the president’s desk. By removing the 60-vote threshold for ending debate—the hurdle that was intended to require consensus among members—Reid enforced the tyranny of the majority upon the Senate. In doing so, he fundamentally changed the nature of the Senate from a body designed around the protection of minority rights to a body that operates more like the majoritarian House.

Q: When Republicans took control of the Senate after the 2014 elections, why didn’t they change the rules back to what they were before?

A: Despite protesting the nuclear option when it was imposed, Senate Republicans have not yet undone it. This means that President Obama’s nominees are still subject to a 51-vote threshold to end debate. And unless the nuclear option is overturned, future Republican presidents will operate under the same terms.

Republicans remain divided as to whether the nuclear option should be undone. Some believe Republicans should maintain it, to utilize if or when a Republican president is in office. Others believe the Senate should reverse itself to the traditional way in which it was run—where debate over confirmation of nominees is ended at the 60-vote threshold.

Q: What are people talking about when they say they want to get rid of the legislative filibuster?

A: When Reid imposed the nuclear option, he eliminated the filibuster for most governmental positions that require Senate confirmation. However, he did not change the filibuster that applies to legislation. The legislative filibuster still exists and requires 60 votes to end debate and bring legislation to a vote.

Some want Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell [R-Ky.] to do to the legislative filibuster what Reid did to the filibuster on nominations—eliminate it, so that debate ends and legislation moves forward by a simple majority of 51 votes instead of the currently required 60 votes.

Q: Considering how gridlocked Washington seems to be and that nothing can apparently get done without 60 votes in the Senate, why is it such a bad idea to eliminate the legislative filibuster?

A: As mentioned, the filibuster is one of the primary characteristics that distinguish the House from the Senate. The House was established to more directly reflect the passions of the people—it moves quickly, and by majority rule. The Senate, on the other hand, was designed to “cool” the passions of the House and act with more deliberation.

James Madison wrote that the Senate should “consist in its proceedings with more coolness, with more system, and with more wisdom” than the majoritarian House. George Washington famously observed: “We pour legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it.”

Put simply, the filibuster is the check on blanket rule by the majority in the House. The filibuster ensures that the minority party in the Senate has a voice in the debate, because without it, the Senate cannot achieve the consensus needed to end debate and move to a vote—which requires 60 votes. The fact of the filibuster forces each side to work with one another, to come to an agreement about final language in a bill, or determine how to deal with competing priorities. In effect, it is a mechanism that forces the “coolness” and the deliberation that Madison and Washington envisioned.

Q: What would be the consequences if the legislative filibuster were removed? Can you give some specific examples?

A: Eliminating the filibuster would have several immediate consequences. First, it would have the practical effect of removing the primary distinctions between the House and the Senate. Complete majority rule would exist across the Congress. While some may argue that, because Republicans are in control, it would be a good thing to have that majority rule, the situation can easily reverse itself if Democrats are in charge.

Second, this majority rule would have the effect of silencing any attempt by minority parties to affect, amend, or otherwise have a say in the legislative process. Think of it this way. What if Democrats held majorities in both the House and Senate, along with the White House?

Any Republican effort to amend legislation, to ask for changes, or to override a presidential veto would be completely stymied. For all intents and purposes, the Republican voice would be silenced. Democrats would have the legislative authority to implement whatever they wanted.

This is not a small matter. Consider for a moment the bills opposed by conservatives that would have faced final consideration in the [Democrat-controlled] Senate and possibly become law, were it not for the legislative filibuster:

- In 2007, President Bush’s immigration reform effort—including provisions providing legal status for many illegal immigrants, opposed by many conservatives—failed to receive the necessary 60 votes to end debate.

- In 2008, the Lieberman-Warner Climate Security Act of 2008—a cap-and-trade carbon tax—failed because of its inability to reach cloture, or 60 votes.

- In 2012, House and Senate Democrats attempted to pass legislation that would enhance the ability of employees to file pay-related lawsuits. The bill failed to receive 60 votes.

- In 2014, the Senate failed to achieve the 60 votes necessary to move to a vote on a bill to override state law in establishing universal background checks for firearm purchases.

- Also in 2014, an attempt by Senate Democrats to amend the Constitution by passing campaign finance measures that would have limited election speech failed to receive 60 votes.

Q: Congress regularly gets low marks for “getting things done.” How do we deal with the fact that the filibuster is one reason legislation has a tough time making its way out of the Senate?

A: It’s true that the use of the filibuster has slowed down consideration of legislation in the Senate over the last several years. But the filibuster has been in place for centuries. Why is it just recently that it seems to have resulted in so much gridlock?

The answer is that the Senate is increasingly run in a far more dictatorial fashion. As I said in another recent Q&A, the past several years have seen an extraordinary accumulation of power in the office of the majority leader. Reid and McConnell, respectively, have used the office to dictate to senators how the body will be run.

This is, historically, out of step with how the Senate has operated for centuries. The Senate is a deliberative body in which every senator is invested with equal authority. Under the tenures of McConnell and Reid, however, that individual authority has been transferred to the office of the majority leader. Rather than run an open Senate, where each senator uses their rights and authorities to call up bills and amendments, the majority leader now deems what amendments and bills deserve a vote.

In the McConnell-Reid era, most agreements are now struck among limited parties of the majority leader’s choosing, without full participation of other senators. Rather than prioritizing the ability of each senator to seek votes, the leaders have prioritized a tightly controlled process that shields politically vulnerable senators from difficult votes and silences other senators who have ideas of which the leadership does not approve.

Without a seat at the table, and without an open forum to exercise their rights, individual senators are left with one outlet—the filibuster. The result is an increased use of aggressive tactics for the simple goal of being heard.

Rather than blame the filibuster for dysfunction and gridlock in the Senate, we should really examine the centralization of power in the office of the majority leader—and question whether that is the best expression of the democratic will.