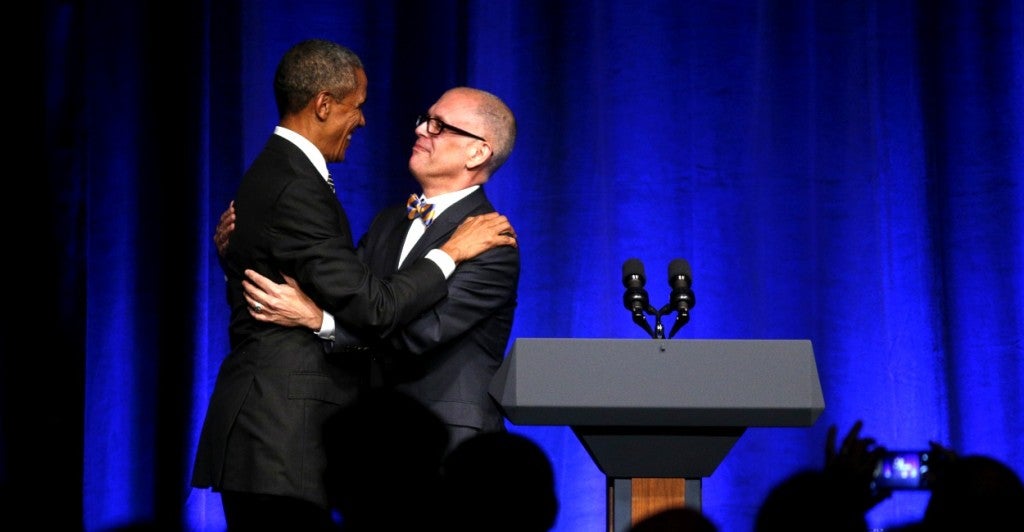

Speaking at a Democratic National Committee LGBT fundraiser on Sunday, President Obama observed that “religious freedom doesn’t grant us the freedom to deny our fellow Americans their constitutional rights.”

Coming from a former constitutional law professor who is now chief executive of the United States, these remarks are a cause for concern.

The sort of constitutional rights of which Obama speaks are all properly understood as restrictions on the power of the state—not entitlements. For instance, the First Amendment guarantees that I will not be prosecuted for criticizing the president, but it doesn’t require The Daily Signal to publish my views.

Even the recently discovered “fundamental right” to same-sex marriage is a restriction on the state’s actions—i.e., states cannot refuse to recognize the marriage between two men or two women. Not even Justice Kennedy believes that the Fourteenth Amendment requires a church, religious organization, or business to recognize or participate in such a marriage.

Obama’s remarks suggest that a minister or businessperson who declines to participate in a same-sex marriage ceremony is denying the couple their “constitutional rights.” But, in what he almost certainly considers to be a major concession, he stipulates that “we” should be “respectful and accommodating [of] genuine concerns and interests of religious institutions[.]”

In light of the Obama administration’s track record, this concession likely means merely that clergy and houses of worship will not be compelled to participate in same-sex wedding ceremonies or recognize same-sex marriages. Given that almost no one is arguing that they should, this concession is meaningless.

The real debate, of course, concerns religious organizations, such as the Christian college at which I teach, and private businesses. Should these institutions be forced to recognize same-sex marriages and/or participate in wedding ceremonies against their sincerely held religious convictions?

Contrary to Obama’s suggestion, their refusal to do either violates no one’s constitutional rights. But it may run afoul of state laws, executive orders, and administrative rules.

What should be done when a general, neutrally applicable law or policy requires someone to violate his or her religious convictions? As I argue in “Religious Accommodations and the Common Good,” a Heritage Foundation backgrounder to be published next week, America has a long and noble history of protecting such individuals. Moreover, the nation and the states have still been able to achieve important policy objectives in spite of these accommodations.

Historically, both Democrats and Republicans have supported religious accommodations. Although a few are limited to clergy and houses of worship, most are not.

Of course, the religious views of clergy should be protected, but so should the convictions of religious institutions and businesspersons who have sincere religious objections to same-sex marriage.