The greatest likelihood for military conflict on the Korean Peninsula is not from a full-scale North Korean invasion, but from a series of escalatory responses to a tactical-level skirmish. This is particularly true if an event occurs during already heightened tensions, as currently exists.

Today’s inter-Korean exchange of artillery fire led to no injuries or deaths and, by itself, will not trigger a broader response. However, the incident adds to an already tremulous and unpredictable environment.

Seoul has reported that North Korea fired several artillery shells into South Korea triggering a South Korean military response by dozens of artillery rounds. The North Korean attack likely was directed at South Korean loudspeakers blaring anti-North Korean propaganda. Earlier this month, Pyongyang vowed “indiscriminate strikes” on South Korea unless Seoul halted the propaganda broadcasts along the DMZ.

Concurrent with the artillery exchange, Pyongyang characterized the broadcasts as a “declaration of war” by South Korea. The General Staff of the North Korean People’s Army warned it would initiate “military action” unless Seoul ceased the broadcasts within two days.

North Korea has increased artillery and anti-aircraft training along the DMZ, including practicing “rolling out artillery cannons from bunkers to aim at South Korean posts.”

Seoul resumed the broadcasts after North Korean soldiers infiltrated and planted a landmine that maimed two South Korean soldiers. South Korea also responded to the landmine attack by changing its military rules of engagement for infiltrations by eliminating the requirement to provide shouted warnings and warning shots prior to directly firing upon the enemy.

Previously, in response to two North Korea naval attacks in 2010, Seoul similarly loosened its maritime rules of engagement by removing restrictions on returning fire. At that time, South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff warned that it would respond to a North Korean attack by “forcefully and decisively striking not only the point of origin of provocation and its supporting forces but also its command leadership.”

South Korean Defense Minister Han Min-koo vowed last week to expand the broadcasts “to full-scale” and indicated Seoul is also considering resuming balloon flights of anti-Pyongyang leaflets into North Korea. In October 2014, the two Koreas exchanged machine gun fire across the DMZ after the North attempted to shoot down propaganda balloons.

Less constrained South Korean rules of engagement, combined with President Park Geun-hye’s exhortation to the military to deal “sternly” to any North Korean provocation raises the potential for a military clash along the DMZ or the West Sea.

The incident occurred during the annual U.S.-South Korean Ulchi Freedom Guardian military exercise which always elicits North Korean threats of military attack.

Pyongyang has often claimed that allied military exercises—such as those currently underway—are provocations that justify North Korean attacks. Pyongyang pledged this month, “If United States wants their mainland to be safe, then the Ulchi Freedom Guardian should stop immediately.”

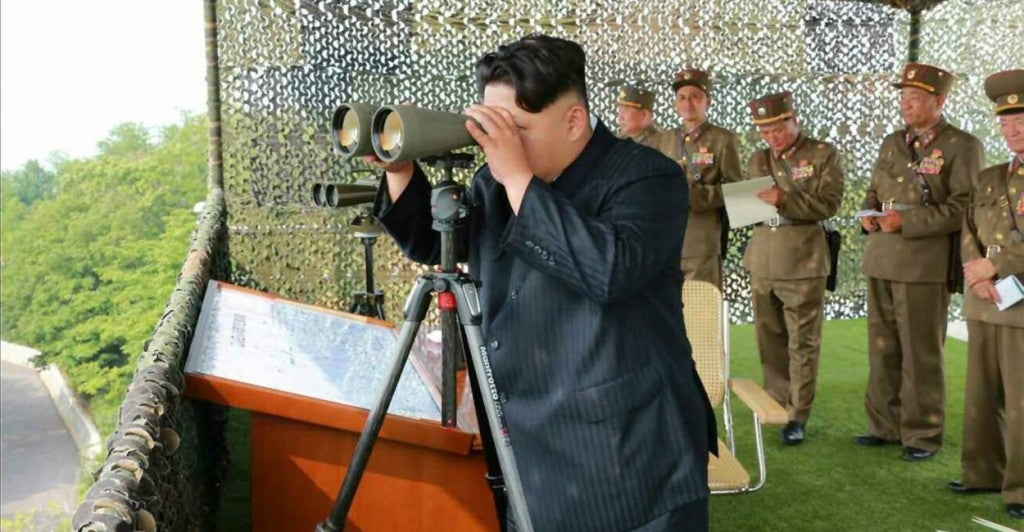

North Korea’s repeated rejection of U.S. and South Korean entreaties for strategic dialogue constrains the likelihood of diplomatically de-escalating tensions. North Korean leader Kim Jong-un appears to be more erratic than his father, increasing the potential for regime miscalculation and Kim stumbling across a red line that triggers an allied response.

Kim’s extensive purges of senior officials have also triggered debate amongst experts over his hold on power and regime stability.