“Believe it or not, all of us are wired up wrong,” Posey tells his pupils, as a gold necklace with a Tweety Bird pendant dangles above his chest.

“I had some loose screws and all that stuff. I still have a few bolts that need tightening, you know.”

As if to reassure them, Posey exhales a pig-squeal laugh that sounds like the most genuine thing in the world.

“For the most part, we are all in the workshop,” he says.

One thing Posey has done that the others haven’t is shoot at and nearly kill a police officer. That offense got Posey, who was 26 years old at the time, a life sentence to prison.

But because God “showed up and showed out” and blessed him “royally,” Posey says, he managed to be paroled after serving 31 years and six months in the “hellhole.”

The 15 or so men and women in his class are lucky, like their teacher, not to be behind bars. But most of them are here because they’ve possessed, consumed or dealt drugs—less serious, nonviolent offenses.

Outside prison’s unforgiving walls, the group is here to learn from Posey, now 59, how to face and move on from their past sins.

They don’t seek forgiveness, necessarily. Before coming here, many experienced plenty of prison and lost the respect of friends and family from whom they could have asked forgiveness.

Instead, they strive for change.

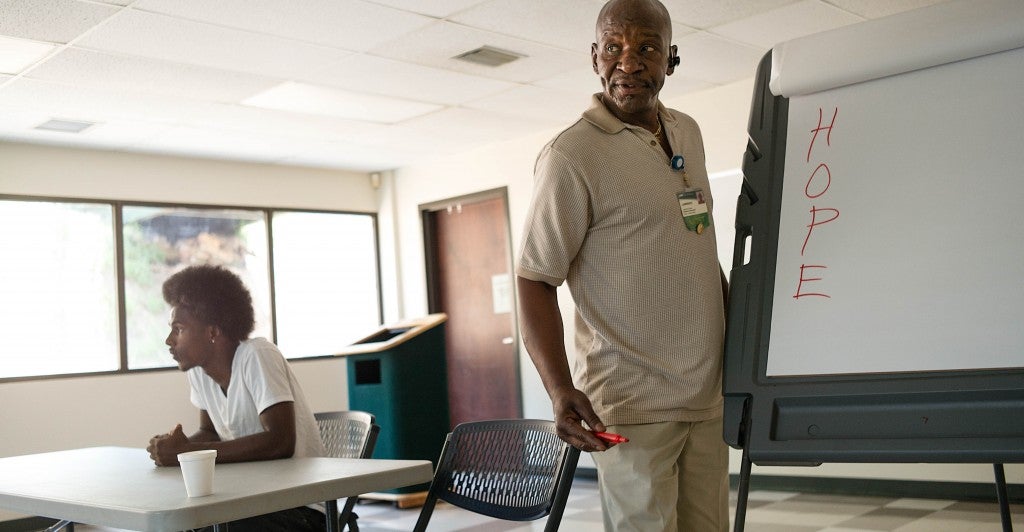

Advocates of criminal justice reform say community-based approaches such as Posey’s class often are more effective than prison in rehabilitating inmates. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

In late June, as part of The Daily Signal’s examination of criminal justice reform in Alabama, a reporter sat in on Posey’s class, called “Thinking for a Change.”

The class is just one offering of the community corrections program in Jefferson County, the state’s most populous. Birmingham, the state’s largest city, is the county seat.

Under a plan to reduce overcrowding in Alabama’s prisons, convicted felons would have greater opportunities to serve their sentences in their home communities rather than prison.

And more offenders returning from prison would come through here, to ease their transition to normal.

Advocates of criminal justice reform say that community-based treatment, available only to nonviolent offenders, provides a more effective outlet to actually serve their needs—to rehabilitate them.

Many of these offenders have a drug problem or mental health issue that prison could exacerbate since it is a place where positive energy and inspiration are hard to find.

Sentencing Outside Prison

“People often ask me, what is the story of the criminal justice reform bill?” says Bennet Wright, director of Alabama’s Sentencing Commission. “It’s really a community supervision reform.”

Wright explains:

The idea is that prison and community-based treatment are two wildly different environments. Just think about it. If you are surrounded by hardened criminals, you are basically doing social networking. That’s how we did criminal justice for a long time: ‘I am going to send you to prison to make you better.’ There’s definitely certain people that need to go. But if someone really is in need of programs and treatments, prison is not the ideal setting for them to get that.

In a community corrections program, adopted and run at the county level, the offender must attend counseling and treatment programs at a facility during the day. In most cases, he or she has the freedom to go home at night.

The criminal justice reform legislation, passed by the Alabama legislature and signed in May by Gov. Robert Bentley, creates a new class of felonies for the least serious nonviolent crimes. These offenders rarely would go to prison. Instead, a judge would have greater discretion to sentence them directly to community corrections.

In addition, because the new law mandates that all those released from prison be supervised in some form, more offenders will serve the back end of their sentences in community corrections.

To meet the growing demand, the reform legislation doubles the $5.5 million currently designated annually for community corrections and provides another $8 million for mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Proponents hope the spending will encourage more counties to launch community corrections programs, which generally are funded with federal, state and local tax money.

Today, community corrections programs exist in only 45 of Alabama’s 67 counties, so it’s not a sentencing option available everywhere in the state—especially in poorer jurisdictions.

For offenders from Jefferson County, where the community corrections program is considered a model for the state, the reform effort would mean at least one good thing: More of them will meet and learn from Lawrence Posey.

‘Play Out the Tape’

Posey’s class is like group therapy, except that in this case the therapist might as well be treating himself, as well as his clients.

When Posey shakes hands, smacks shoulders and calls members of his class by their first names, he’s letting them know he’s here with them. He constantly wears a Bluetooth earpiece so they know he’s available to mentor them whenever.

This day, Posey opens by writing out an acronym in pink letters: HOPE (Hearing Other People’s Experiences).

“Hearing other people’s experiences gives us hope—feel me?” he says, and the class repeats the phrase.

Before they can embrace their freedom, Posey wants these men and women to revisit the moment when they lost it.

By returning to the moment they committed a crime, the offenders must confront the criminal mindset that agitated the moment, and learn to hate it. Once they know to reject criminal thinking, they can accept rational, normal thoughts and create new moments that don’t result in a prison sentence.

Posey, who served 31 years of a life sentence for attempted murder, tries to connect with inmates on a personal level. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

Everyone here has had the criminal moment.

Posey will gladly tell you about his.

He pokes his shiny scalp with an index finger to recall the thinking that inspired him to attempt murder:

I went to prison, and spent 31 years and six months in that hellhole, because I was a damn fool. You can’t be more foolish than I was. If a fool like me can see the light, then, boy, I know that anybody with breath in their body can. That’s the absolute truth.

Though prison is dark, Posey found light.

Posey found light in education, and he used course offerings in prison to get a degree.

He found it in religion, and the crucifix hanging from his neck began to mean something.

He found a little-used law library, learned to litigate and began building a case to leave prison.

And he turned his findings into opportunity, eventually benefiting from a special petition allowing judges to reconsider sentences of life without parole for certain violent offenders.

Posey recalls:

I had a change of heart. See, not everybody is as fortunate as I am to make it here. Life without parole—that means you ain’t ever gonna get out of prison. You gonna die. But God said not so, I got something for him to do. And he really showed up and showed out. Cause I ain’t been out four years quite yet, and he blessed me royally. All you gotta do is change directions. It will work for you, too.

“Change directionsss,” Posey repeats, dragging out the “s.”

Decisions With Consequences

There are plenty of chances to change directions—to turn their lives around— Posey tells the class, because decisions happen every day.

Every person in this class decided to come: the kid who missed prom because he robbed a store with a toy gun, the woman who blames her bad decisions on having a well-off “momma and daddy do everything for me,” the father who volunteered to be here because he wants to win his children back.

‘It hurts’: Kenneth Jackson, 22, recently released from prison after a robbery conviction, says he ‘missed out on a lot.’ (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

Though they get to live at home during their time here, everyone sent to community corrections is still considered an inmate. So if they don’t decide to show up for this 9 a.m. class, they can be punished—even if a return to prison is rare.

“Your life depends on decisions,” Posey says. “Whether they are good or bad, they have consequences. A lot of times if we stop and think about it, we would make better decisions.”

Posey has a phrase for this decision-making process:

You better play out the tape; if we play out the tape, we will make a better decision. If we had to play out the tape with some choices we made to be here, we would have made some different choices. If our best thinking got us here, we weren’t thinking too good, right? That’s deep.

The nationally developed curriculum Posey uses describes this lesson a bit more elegantly:

“Using important thinking skills such as brainstorming and imagining the consequences of your actions,” the PowerPoint slide reads.

‘Curriculum With Credibility’

Posey’s unique brand of teaching is what makes the class effective.

And Posey is not here by accident.

Foster Cook, a small man with a big heart and heavy Southern accent, directs Jefferson County’s community corrections program.

As part of the program, which is formally called Treatment Alternatives for Safer Communities, Cook has made it a point to hire ex-felons—known as “peers”—to teach the offenders who come through here.

When inmates from Jefferson County leave prison, Posey or another assigned peer is usually who picks them up and drives them home.

Posey is one of Cook’s favorite projects. The program director’s cheeks brighten when he talks about him.

“He has credibility and authority that I don’t have,” Cook, 69, says of Posey, who is still on parole.

Cook is quick to emphasize that Posey—and the 11 ex-offenders employed here—do more than simply relate to the inmates with real talk and street cred:

They bring credibility to it, but they are actually doing something. They are not just saying, ‘I remember when I was in prison. Remember those old boys down there? I whooped them.’ You could go on and on talking about your story. That’s not what they are there for. They are there to deliver this curriculum with credibility. Because it works.

Posey and the other employees, who have to be at least two years removed from prison to be hired here, are schooled to teach the “Thinking for a Change” course.

“Thinking for a Change” is a cognitive behavior training program developed by the National Institute of Corrections at the U.S. Justice Department.

The program, created in 1998 with the aim to help offenders make better decisions by encouraging self-reflection, social skills and problem-solving, has proven effective in reducing recidivism.

Ralph Hendrix (left) and Foster Cook lead Jefferson County’s community corrections program with an eye toward reducing recidivism. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

In 2011, Cook began offering the course in Jefferson County. Upon being hired in 2012, Posey traveled to Baltimore to learn how to teach it.

The course, meant for those considered at a medium to high risk to commit a crime again, is the first thing offenders do after entering Jefferson County’s community corrections program.

The class runs Monday through Friday for four weeks. Participants receive bus money to get to class and a free meal to sustain themselves through it. They also get help in finding housing. Most don’t try to find employment initially; research says it’s better they take care of personal business first.

Everyone immediately takes a risk assessment to determine his or her case plan.

Besides “Thinking for a Change,” Jefferson County’s Treatment Alternatives for Safer Communities offers mental health programs and drug courts and a veterans court.

These “therapeutic courts” allow offenders to get treatment under the supervision of a special judge, who tracks their progress and can give them more punishment if they fail.

In Jefferson County, if an offender makes it through one of these courts, he or she can have charges dismissed.

‘No Crystal Ball’

Cook, employed by the University of Alabama-Birmingham’s Department of Psychiatry since 1978, is the man responsible for making Jefferson County’s community corrections program so comprehensive.

Cook, in aggressively soliciting federal and state dollars to boost the programming, says he has secured more than $65 million in grants and contracts since 1990.

In launching the nation’s oldest alternative treatment program in 1973, Jefferson County was the first to partner the criminal justice system with mental health treatment.

The White House recognized the initiative in the 1990s for confirming that community-based treatment can reduce recidivism dramatically.

Today, as of July 23, Jefferson County is serving 672 offenders. The number includes 580 who were sentenced directly to community corrections and 92 who have done time in prison and are serving the rest of their sentence here.

Ernest Briggins, 57, says it’s ‘ridiculous’ he got 30 years for selling some crack when he never did a violent crime. He’s finishing his sentence in community corrections. (Photo: Josh Siegel/The Daily Signal)

In 2013-14, of those who came to Jefferson County from prison through the reentry program, 80 percent successfully completed their treatment plan.

In addition, 90 percent remained off drugs and alcohol after six months, and 69 percent were employed or attending school in that same period.

Cook credits his program’s success to a quality that it tries to teach offenders: relationship-building.

For a judge to sentence a felon to community corrections, he must be confident in his decision to let the offender do the time in the community—and not behind bars.

“Judges have to trust you and believe you are credible,” Cook says. “Unless you have a relationship with the judges, you can’t do what we need to do. You have to deliver what you promised.”

Judges, who understand the costs of prison better than most by sending men and women there, say they want to be sure before delivering an alternative sentence.

But they can’t be so sure.

“One of our problems is we don’t have a crystal ball; we don’t know,” says Laura Petro, a judge in Jefferson County Circuit Court who is comfortable enough with Cook that she is eating lunch with him on a summer day.

Petro says:

Last year, I had two or three people on the community corrections docket die of heroin overdoses. This year, two of my community corrections people murdered people. We do the best we can with the information we have. But really, the best information we are getting is from community corrections, after they’ve been monitoring them for a while. We are dependent on them to give us options.

Bar Set to ‘Another Level’

Cook wants to provide more options.

As part of the criminal justice reform bill’s emphasis on community supervision, he submitted a first-of-its-kind proposal to the state to serve more offenders.

The plan would require every single incarcerated man and woman from Jefferson County to be served by Cook’s alternative treatment program when he or she returns home from prison.

This way, every offender re-entering society would receive the same kick-start: Each would get a risk-needs test, a case plan and access to the county’s alternative treatment services.

Each would have a chance to take the “Thinking for Change” course—and, if he or she is lucky, interact with Lawrence Posey.

“I’ve been doing this for 41 years; I know exactly what these programs look like and how they ought to operate,” Cook says matter-of-factly, without cockiness.

“The bar is set at another level now.”

Posey constantly wears a Bluetooth earpiece so the men and women in his class know he’s available to help at any time. (Photo: Bob Miller for The Daily Signal)

The higher bar goes beyond Cook’s proposal, which, like the reform legislation itself, has not yet been funded.

The new law requires more demanding standards for community corrections.

It enforces accountability, mandating that such programs reduce recidivism by a specific amount.

It forces community corrections to use the risk-needs assessments to determine how intensely to devote supervision resources to each offender. (Jefferson County already does this.)

Making an Accurate Diagnosis

Currently, Alabama has no standards for community corrections programs to measure results, such as forcing adherence to scientifically proven methods to reduce recidivism.

There is also no way to ensure accountability for how jurisdictions use funding, but that is supposed to change under the reforms.

The bolstered supervision process reinforces just how serious the consequences are.

Research shows that offenders are more likely to commit new crimes within the first year of release from incarceration. Yet about one-third of those who left Alabama prisons in fiscal year 2013—most were in for lower-level offenses—had no supervision.

“If I come in with an offender, that offender needs to be diagnosed correctly,” says Wright, the Sentencing Commission director.

Wright explains:

It’s like if you were to walk in with your doctor and say, ‘Hey, Doc, I’ve got some chest problems.’ You probably don’t want him to just saw off your chest and do open heart surgery. You want a full diagnosis. It’s one thing to say this person has a high risk of recidivism. It’s another thing to say, well, he has a substance abuse problem. If we get that treated, his likelihood to commit [another] crime goes down. That is what the [state] Senate bill encourages. It encourages everyone to make a full and accurate diagnosis of the felony offender and make the best use of the resources so that person doesn’t commit another crime.

In Alabama, around half of all offenders complete their sentence in prison and then are released without supervision.

With no one on the outside to show them another way, they often return to where their troubles began.

In class, Posey is explaining how going back to the same “people, places and things” makes it convenient—almost too easy—for an ex-felon to strike again. And that means another date with prison.

“We’ve all had this experience,” says Posey says.

He may have been convicted of attempted murder, but it was far from his first offense.

One Father’s Story

“I know I have experienced it exactly,” confesses Darrel Darden, a broad-chested three-time felon in Posey’s class.

Darden’s misdeeds led to his missing a lifetime of experiences with his four children. Finally in control of his life again, he has volunteered to be here.

After serving 15 years of a 25-year sentence in prison, Darden was paroled in May.

The terms of parole don’t require him to attend Jefferson County’s reentry program or Posey’s class—only that he report once a month to a parole officer.

But Darden, now 53 and in and out of prison since 1992, blew his previous chances at freedom. He says he won’t let this one go.

Because he had completed his two previous sentences in prison, Darden was not supervised upon release.

So now, he has taken upon himself to ensure that somebody—and some place—watches over his transition, and mentors him along the way.

“I want a different way of life from what I normally led when I got out of prison,” says Darden, whose most recent conviction was for third-degree burglary and possession of a controlled substance. He adds:

You have to change yourself in order for your environment to change. You can’t sit at home on the couch and say, ‘Oh, Lord, please help me to change, please help me to change.’ Nah, you have to go out and do something. That’s why the word of God says, ‘Faith without works is dead.’

For Darden, change began to come during his most recent time in prison. He arrived already planning his exit.

While incarcerated, he helped run all of the drug treatment programs. In all his years in prison, he earned only one disciplinary action.

“I went in prison trying to get out of prison,” Darden says. “I didn’t get there to stay there. That’s why I took every program the state had to offer. They call you an inmate. They call you a convict. I never wanted to be labeled that. I never want to think that way. I never wanted to institutionalize mentally.”

He does want to be labeled a father. But his four children don’t know him as that.

It’s About the ‘Stay Out’

When he was present, Darden says, he taught his children lessons he thought they should know. He can’t be sure they learned:

When my boys were young, I taught them how to be men. I taught them how to open doors for a young lady. I taught them how to be respectful, how to not sag your pants. I took them and gave them the basics of being a man. But to actually see me being that man, I was absent and that hurts me today. That’s pretty devastating.

The children are young adults now. Darden knows some things about them, for instance what they’re doing. His oldest daughter is a cosmetologist. The youngest finishes high school next year. His two sons have graduated college.

Because of the distance he put between himself and his children, he doesn’t know how they got there.

He’s willing to take baby steps to be accepted as part of their future:

Sometimes it’s too late to be a father. But I can be a friend, and then that friendship can develop to me being a dad, me being their father again.

That’s why Darden has come to Posey’s class, even if his children don’t know he’s here.

He’s betting that by his doing the right things, they will recognize him eventually.

“I have goals,” Darden says. “I have short-term goals, medium-range goals and long-term goals. When I reach my medium-range goal, they will know I am here.”

Convinced, he says it again: “They will know that I am here.”

The goal is to be a counselor. Kind of like Posey. So he’s here, observing. His mentor watches back, making sure Darden remains on track.

“I’ve come to realize if you stay in prison long enough, they are gonna let you go,” Darden says. “Everybody worries about the get out, but what about the stay out?”