The growing battle over the College Board’s Advanced Placement U.S. History (APUSH) framework is being described by Politico and others as the usual scrape over American exceptionalism. It is that to a point, of course. But it is really about national survival.

The continuation of self-government and liberty depends on the willingness of citizens to sacrifice for a greater good, which in turn relies on a sound educational grounding on civic virtues. The College Board’s latest framework seems almost intended to rupture these connections.

The College Board is a non-profit organization that for decades has administered advanced placement tests to about half a million high school students. In order to help teachers prepare their charges for the tests, the College Board gives “thematic” guidance. Thus its frameworks.

The current framework, published last fall, has been put together for years by a group of college history professors gathered together by the College Board. And this is what dooms it, in the eyes of many, many critics: The framework, like the Obama administration-supported Common Core, represents another attempt to nationalize education and reflects the reflexive anti-American bias of the faculty lounge.

According to Peter Berkowitz, it obsesses over “inequalities of race and gender,” “the European conquest of native peoples, economic exploitation and environmental abuse.”

Last week, no fewer than 55 distinguished scholars and historians said enough, releasing a joint letter expressing their strong opposition to the latest framework. “This interpretation,” it read, “downplays American citizenship and American world leadership in favor of a more global and transnational perspective.”

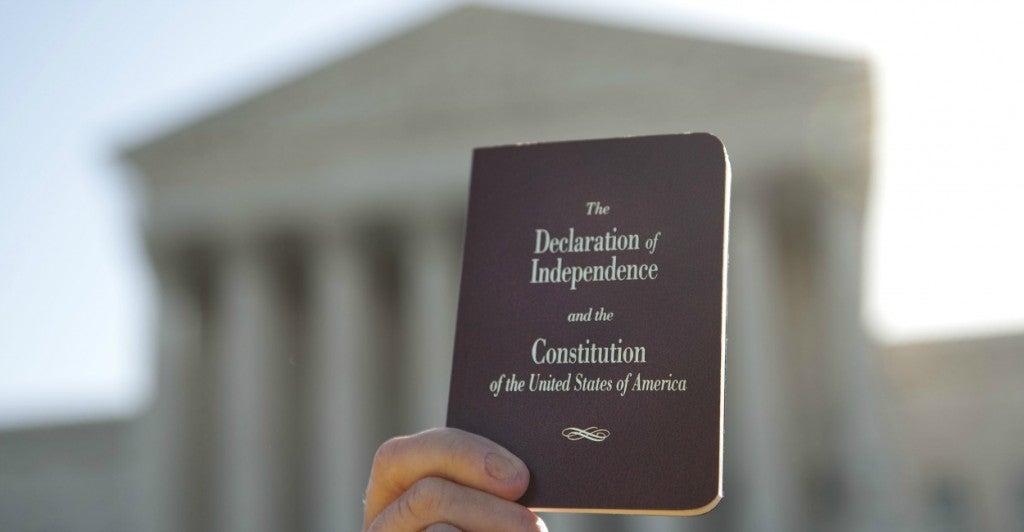

“The new framework is organized around such abstractions as ‘identity,’ ‘peopling,’ ‘work, exchange, and technology,’ and ‘human geography’ while downplaying essential subjects, such as the sources, meaning, and development of America’s ideals and political institutions, notably the Constitution,” said the 55 signers.

It is difficult to argue with the framework’s critics. A typical passage in the 134-page document reads:

Students should explore the lives of working people and the relationships among social classes, racial and ethnic groups, and men and women, including the availability of land and labor, national and international economic developments, and the role of government support and regulation.

The letter writers do not ask for a whitewash of U.S. history, but rather “a robust, vivid, and content-rich account of our unfolding national drama, warts and all, a history that is alert to all the ways we have disagreed and fallen short of our ideals, while emphasizing the ways that we remain one nation with common ideals and a shared story.”

Such emphasis on what we share and fellow feeling is necessary for a free republic like the U.S.

The two great ages associated with self-government and liberty, Ancient Greece and the Enlightenment, agreed that education was indispensable to forging an emotional attachment to the nation and its principles. “Everything, therefore, depends on establishing this love in a republic; and to inspire it ought to be the principal business of education,” wrote Montesquieu.

The Founding Fathers concurred. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison especially wrote about this link between education and patriotic feeling. The latter had to buttressed by something deeper than mere practicality, but by an attachment to something bigger than ourselves.

This link between liberty, patriotism and education is all the more important in a nation like the United States, made up as it is of immigrants from every continent. Just last month Yale University historian Donald Kagan said in a lecture:

Free countries like our own have an even more powerful claim on the patriotism of their citizens than do other kinds of countries. But it seems to be our country has even greater need of it than most.

Every country requires a high degree of cooperation and unity among its citizens if it is to achieve the internal harmony that any good society requires … Most countries have relied on the common ancestry and the traditions of their people as the basis of their unity. But the United States of America can rely on no such commonality; we are an enormously diverse and varied people; almost all immigrants or the descendants of immigrants … we are always vulnerable to divisions among us, which can be exploited to set one group against another and to destroy the unity and harmony that has allowed us to flourish. We live in a time when civil demotion has been undermined and national unity is under attack constantly.

Kagan made no mention of APUSH, but he might as well have.