In recent months, heartbreaking stories of Americans such as Brittany Maynard struggling with devastating diagnoses have captured our empathy—and launched a national conversation about physician-assisted suicide. In response, activists are using these stories to advance legislation that has otherwise been rejected by the people.

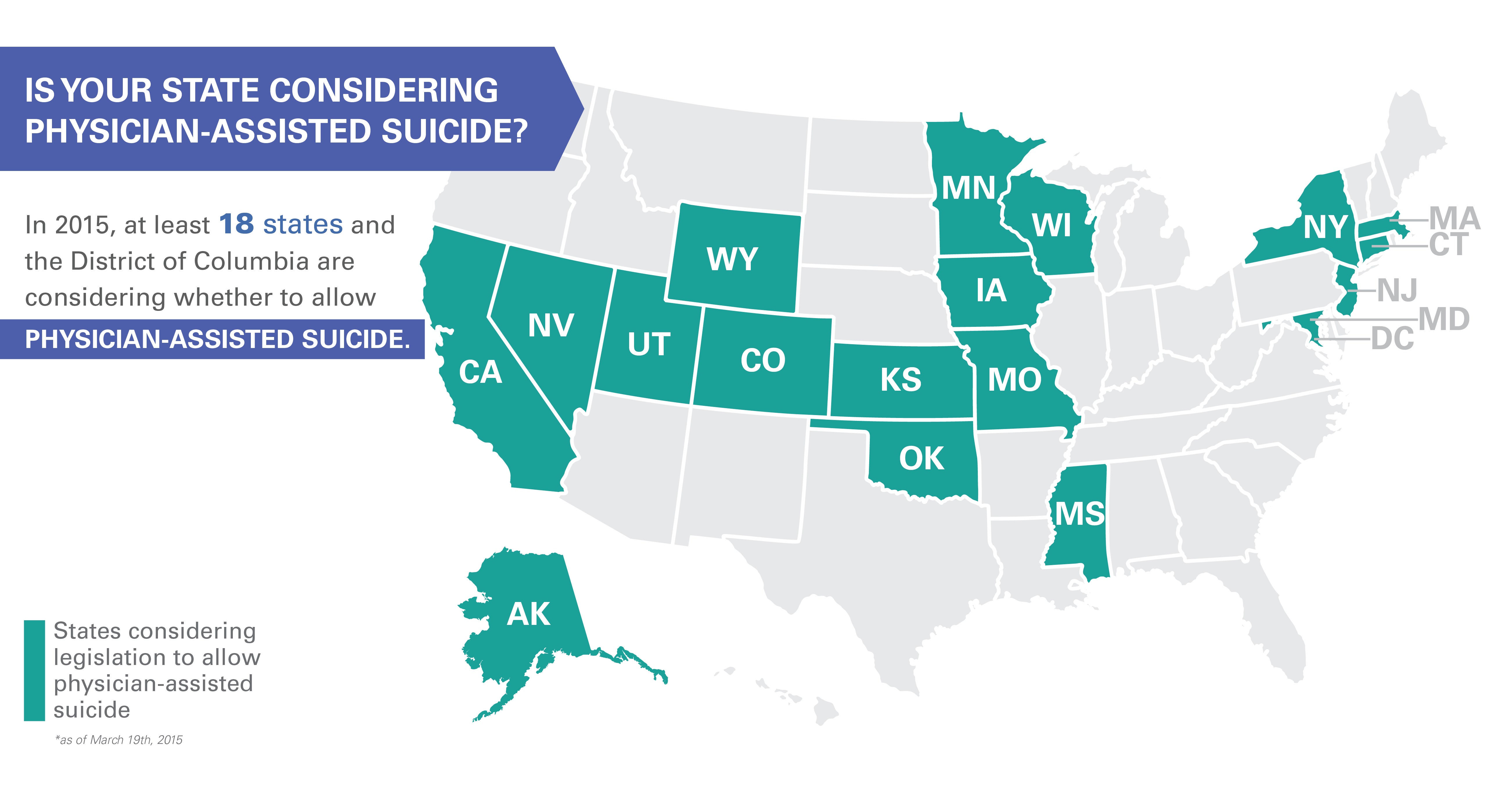

At least 18 states across the country are considering whether to allow physician-assisted suicide. But legalizing physician-assisted suicide would be a grave mistake.

The merciful thing would be to expect doctors to do no harm and ease the pain of those who suffer and support families and ministries in providing that care.

Indeed, that was the message of Sen. Ted Kennedy’s widow as she campaigned against physician-assisted suicide in Massachusetts in 2012. Victoria Reggie Kennedy pointed out that most people wish for a good death “surrounded by loved ones, perhaps with a doctor and/or clergyman at our bedside.” But with physician-assisted suicide, “what you get instead is a prescription for up to 100 capsules, dispensed by a pharmacist, taken without medical supervision, followed by death, perhaps alone. That seems harsh and extreme to me.”

Indeed it is.

The Hippocratic Oath proclaims: “I will keep [the sick] from harm and injustice. I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody who asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect.” This is an essential precept for a flourishing civil society. No one, especially a doctor, should be permitted to kill intentionally, or assist in killing intentionally, an innocent neighbor.

Human life doesn’t need to be extended by every medical means possible, but a person should never be intentionally killed. Doctors may help their patients to die a dignified death from natural causes, but they should not kill their patients or help them to kill themselves. This is the reality that such euphemisms as “death with dignity” and “aid in dying” seek to conceal.

Legalizing physician-assisted suicide, however, would be a grave mistake, as explained in a new Heritage Foundation report. It would:

- Endanger the weak and vulnerable,

- Corrupt the practice of medicine and the doctor–patient relationship,

- Compromise the family and the relationships between family generations and

- Betray human dignity and equality before the law.

To understand the problems with physician-assisted, one must understand what it entails and where it leads.

What Is Physician-Assisted Suicide?

With physician-assisted suicide, a doctor prescribes the deadly drug, but the patient must take the drug himself. While most activists in the United States publicly call only for physician-assisted suicide, they have historically advocated not only physician-assisted suicide, but also euthanasia: the intentional killing of the patient by a doctor.

The Supreme Court has ruled in two unanimous decisions that there is no constitutional right to physician-assisted suicide.

This is not surprising: The arguments for physician-assisted suicide are equally arguments for euthanasia. Neil Gorsuch, currently a federal judge, points out that some contemporary activists fault the movement for not being honest about where its arguments lead. He notes that legal theorist and New York University School of Law professor Richard Epstein “has charged his fellow assisted suicide advocates who fail to endorse the legalization of euthanasia openly and explicitly with a ‘certain lack of courage.’”

The logic of assisted suicide leads to euthanasia because if “compassion” demands that some patients be helped to kill themselves, it makes little sense to claim that only those who are capable of self-administering the deadly drugs be given this option. Should not those who are too disabled to kill themselves have their suffering ended by a lethal injection?

And what of those who are too disabled to request that their suffering be ended, such as infants or the demented? Why should they be denied the “benefit” of a hastened death? Does not “compassion” provide an even more compelling reason for a doctor to provide this release from suffering and indignity?

Although the Supreme Court has ruled in two unanimous decisions that there is no constitutional right to physician-assisted suicide, three states permit it by statute: Oregon, Washington and Vermont.

Four Problems with Physician-Assisted Suicide

As explained in The Heritage Foundation Backgrounder “Always Care, Never Kill,” physician-assisted suicide is bad policy for four reasons:

1. Physician-assisted suicide endangers the weak and marginalized in society. Where it has been allowed, safeguards purporting to minimize this risk have proved to be inadequate and have often been watered down or eliminated over time.

Physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia are allowed in three European countries—the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg—and Switzerland allows assisted suicide.

The evidence from these jurisdictions, particularly the Netherlands, which has over 30 years of experience, suggests that safeguards to ensure effective control have proved inadequate. In the Netherlands, several official, government-sponsored surveys have disclosed both that in thousands of cases, doctors have intentionally administered lethal injections to patients without a request and that in thousands of cases, they have failed to report cases to the authorities.

People who deserve society’s assistance are instead offered accelerated death.

2. Physician-assisted suicide changes the culture in which medicine is practiced. It corrupts the profession of medicine by permitting the tools of healing to be used as techniques for killing. By the same token, physician-assisted suicide threatens to fundamentally distort the doctor–patient relationship because it reduces patients’ trust of doctors and doctors’ undivided commitment to the life and health of their patients.

Moreover, the option of physician-assisted suicide would provide perverse incentives for insurance providers and the public and private financing of health care. Physician-assisted suicide offers a cheap, quick fix in a world of increasingly scarce health care resources.

3. Physician-assisted suicide would harm our entire culture, especially our family and intergenerational obligations. The temptation to view elderly or disabled family members as burdens will increase, as will the temptation for those family members to internalize this attitude and view themselves as burdens. Physician-assisted suicide undermines social solidarity and true compassion.

4. Physician-assisted suicide’s most profound injustice is that it violates human dignity and denies equality before the law. Every human being has intrinsic dignity and immeasurable worth. For our legal system to be coherent and just, the law must respect this dignity in everyone. It does so by taking all reasonable steps to prevent the innocent, of any age or condition, from being devalued and killed.

Classifying a subgroup of people as legally eligible to be killed violates our nation’s commitment to equality before the law—showing profound disrespect for and callousness to those who will be judged to have lives no longer “worth living,” not least the frail elderly, the demented and the disabled. No natural right to physician-assisted suicide exists, and arguments for such a right are incoherent: A legal system that allows assisted suicide abandons the natural right to life of all its citizens.

Sen. Ted Kennedy and his wife Victoria Reggie Kennedy in 1998. (Photo:Richard Ellis/ZUMAPRESS/Newscom)

The Alternative: True Compassion and Care

Instead of embracing physician-assisted suicide, we should respond to suffering with true compassion and solidarity. People seeking physician-assisted suicide typically suffer from depression or other mental illnesses, as well as simply from loneliness. Instead of helping them to kill themselves, we should offer them appropriate medical care and human presence.

For those in physical pain, pain management and other palliative medicine can manage their symptoms effectively. For those for whom death is imminent, hospice care and fellowship can accompany them in their last days. Anything less falls short of what human dignity requires. The real challenge facing society is to make quality end-of-life care available to all.

People seeking physician-assisted suicide typically suffer from depression or other mental illnesses, as well as simply from loneliness.

Doctors should help their patients to die a dignified death of natural causes, not assist in killing. Physicians are always to care, never to kill. They properly seek to alleviate suffering, and it is reasonable to withhold or withdraw medical interventions that are not worthwhile. However, to judge that a patient’s life is not worthwhile and deliberately hasten his or her end is another thing altogether.

Victoria Reggie Kennedy has said it best:

My late husband Sen. Edward Kennedy called quality, affordable health care for all the cause of his life. [PAS] turns his vision of health care for all on its head by asking us to endorse patient suicide—not patient care—as our public policy for dealing with pain and the financial burdens of care at the end of life. We’re better than that. We should expand palliative care, pain management, nursing care and hospice, not trade the dignity and life of a human being for the bottom line.

Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life by alleviating pain and other distressing symptoms of a serious illness. Palliative care is an option for people of any age at any stage in illness, whether that illness is curable, chronic or life-threatening.

Citizens and policymakers need to resist the push by pressure groups, academic elites, and the media to sanction physician-assisted suicide. For more on this, read “Always Care, Never Kill.”